In this fascinating book, Adam D. Mendelsohn paints a vivid picture of how “rag picking” in nineteenth-century England and the United States served as the springboard for Jews to enter the middle and upper classes. Dealing in secondhand clothes offered a perfect Jewish “ethnic niche.” It was an aspect of the garment industry that provided few occupational barriers. Little cash was needed to open a stall or store, and none for scouring the street. The stigma of the work made it unappealing and reduced the number of competitors. Itinerant collectors bought, begged, and bartered to get clothing, which in turn was cleaned, repaired, and sold or repurposed into totally new items such as bonnets, cloaks, and aprons. In London there was far more secondhand clothing available and a greater demand for inexpensive clothes, leading to the development of an elaborate system of trade of castoff clothing. In 1843, “The Clothing Exchange” was established and drew over ten thousand people on Sunday, the busiest day. There were one to two thousand Jewish collectors walking the streets of London collecting old clothes to resell or repurpose. This extensive secondhand clothing business schooled Jewish garment entrepreneurs in the production and marketing skills they would later need as manufacturers and retailers of new clothes.

In New York, the development of the garment industry took a slightly different route. There was less used clothing available. Jewish peddlers went into the used clothing trade but in much smaller numbers than their coreligionists in London. Instead, a sizeable number of Jewish men became dry goods peddlers who spread out over the country, drawn by the booming consumer economy in newly developing towns across the nation. The demand for inexpensive clothes remained strong in New York and across the nation. The garment industry responded by developing an inexpensive “ready-made” industry, replacing artisan tailors who created the garment from start to finish with a system of poorly paid “outworkers” to do “piecework.” A manufacturer would begin the process by purchasing and cutting the cloth which was then sent to “outworkers” to finish the process. In 1855, “outworkers” made up an astonishing 91 percent of the workers in the garment industry.

Jews worked on all levels of the American garment industry. They drew upon their Jewish ethnic interconnected network to hire themselves out as workers and to start their own businesses. In 1910, more than 50 percent of Russian-born Jewish men and 44 percent of American-born Jewish men were employed in the production, retail, or wholesale of clothing. Jewish female garment workers typically worked from adolescence until marriage or the birth of their first child, after which they withdrew from full-time work. The garment industry provided many Jewish livelihoods. These experiences in turn led Jews to carve out other new business niches in the entertainment business in Hollywood and Broadway theatre. These entrepreneurial ventures, coupled with their determined efforts to make sure their children received a high education, catapulted American Jews into highly successful lives.

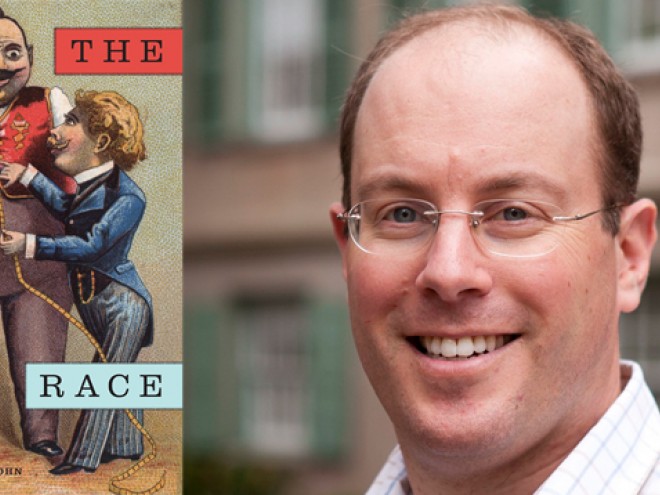

Mendelsohn brings a special expertise to his analysis. He was born in South Africa and draws fascinating comparisons between the Jewish role in the garment industry in the United States and across the British Empire, including in South Africa, Canada, and of course London. The Rag Race: How Jews Sewed Their Way to Success in America and The British Empire is an enthralling story that helps explain why the garment industry has sometimes been affectionately referred to as the “shmatte (rag) business.”

Related content:

- Royal Young: Crossing Delancy: On Lee Brozgold

- Liana Finck: My Influences Are Showing

- A Perfect Fit: The Garment Industry and American Jewry, 1800 – 1960 edited by Gabriel M. Goldstein and Elizabeth E. Greenberg

Read Adam D. Mendelsohn’s Posts for the Visiting Scribe

Stumbling on Jewish Suppliers to the Confederacy

How Can We Explain Jewish Success in America?

Meet Sami Rohr Finalist Adam D. Mendelsohn

Jewish Book Council is proud to introduce readers to the five emerging nonfiction authors named as finalists for the 2016 Sami Rohr Prize for Jewish Literature. Today, we invite you to learn more about Adam D. Mendelsohn and his book, The Rag Race: How Jews Sewed Their Way to Success in America and the British Empire, a vivid picture of how “rag picking” in nineteenth-century England and the United States served as the springboard for Jews to enter the middle and upper classes.

A warm congratulations to Adam and the other four finalists: Yehudah Mirsky, Aviya Kushner, Dan Ephron, and Lisa Moses Leff. Be sure to check back soon to see which of these authors will be taking home the $100,000 prize!

What are some of the most challenging things about writing nonfiction?

Two things. Firstly, deciding on the right moment to switch my energies from research to writing. The temptation is so strong to keep on digging, to follow one more lead, to ferret out additional detail (pick your preferred metaphor!). I find that much of the excitement of any research project comes from this initial exploratory phase: the thrill of the chase. But at some point the hunt has to take second place to the business of writing. And secondly, I am unsettled by an awareness that any historical project is so much the product of happenstance — the survival of particular archival collections; an accumulation of authorial decisions, some made knowingly, others unwitting; the necessity of selection; the whims and interests of the writer.

What or who has been your inspiration for writing nonfiction?

Many inspirations, but one is the sheer pleasure I get from reading books that teach me new things and force me to think in new ways. If I am able to produce work that gives similar pleasure to others, I’d be delighted. Mission accomplished.

Who is your intended audience?

This book was written with an academic audience in mind, but with the aim of making it accessible to as wide a readership as possible. I like to believe that the question I grapple with at the heart of my book — why have Jews prospered so dramatically in America— is one that Jews and others should be thinking about. If Jewish success is not solely the product of the particular cultural baggage carried by Jews to these shores, then the experience of Jews has enormous potential relevance to more recent immigrant groups.

Are you working on anything new right now?

Many projects large and small. I’m overseeing a study — the first of its kind — attempting to track the attitudes of black South Africans toward Jews. I’m annotating the candid travel diaries of a nineteenth-century Jamaican Jew. And I’m in the early stages of a project about a curious episode that took place in Ethiopia in 1868.

What are you reading now?

My reading is schizophrenic. If I’m lucky I get to read something more serious in-between recitations of Winnie the Witch and The Gruffalo to my kids. I have a guilt-inducing stack of New Yorkers sitting on my bedside table. I am a voracious reader of novels (most recently Julian Barne’s The Sense of an Ending and David Benioff’s City of Thieves). And I am busy with a brilliant new book about the concentration camp system called KL.

If you had to list your top five favorite books…

Here are some that have influenced me:

Homage to Catalonia by George Orwell

One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

Replenishing the Earth by James Belich

Culture of the Jews by David Biale (and others)

The Drowned and the Saved by Primo Levi

When did you decide to be a writer? Where were you?

I’ve always enjoyed words — as a teenager I’d peruse the dictionary for pleasure. But I only truly discovered the thrill of writing nonfiction as a university student. For me the pleasure comes both from the research and the puzzle-game of getting a sentence right.

What is the mountaintop for you — how do you define success?

Finding a fresh idea or novel perspective, and presenting it clearly and persuasively. Occasionally I’ll chance across something that is startlingly original, but is so obvious (in a good way) once it has been fleshed out.

How do you write — what is your private modus operandi? What talismans, rituals, props do you use to assist you?

Pajamas help. But otherwise all I need is a problem to solve, typically a sentence that needs puzzling over. Once I get stuck in, the text takes over.

What do you want readers to get out of your book?

I do not for one moment imagine that I’ve written the definitive book about the economic success of Jews in America. Instead I hope to trouble the waters a little, persuading readers to think again about what role culture has played in this process, and perhaps to reassess the conventional wisdom.

Adam Mendelsohn is Associate Professor of History and Director of the Isaac and Jessie Kaplan Centre for Jewish Studies and Research at the University of Cape Town, the only such center in Africa.

Related Content: