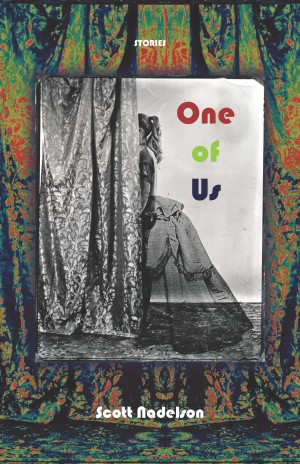

Illustration by Jenny Kroik, cropped

Join Scott Nadelson and Paper Brigade’s editors to kick off the third season of Paper Brigade’s Short Story Club on March 12th at 12:30 p.m. ET on Zoom. Register here!

In the census of 1784, when Slutsk was still part of the Polish – Lithuanian Commonwealth, he appears as Itsko Polak, or Isaac the Pole. By 1811, after the town had been absorbed into the Russian Empire, where Jews were required to provide inheritable surnames for the purpose of taxation, he shows up as Itsko Edelman. In Yiddish, the new name translates as “nobleman,” though no one then or later took this meaning literally: his descendants, living humble lives as tradesmen, shopkeepers, and laborers, assumed he’d been so designated because of his character, and they tried to live up to the nobility of their namesake by accepting their meager circumstances with dignity. They were model citizens, paying their taxes in full and without complaint. They cheered Russian victories against Napoleon, the Persians, and the Turks, and contributed what they could to a fund for returning soldiers. And when Tsar Nicholas I lifted the long-standing ban on conscripting Jews into military service, they watched their sons leave to fight and die in the Crimea. About this, too, they complained only in private, hiding their anguish from gentile neighbors and carrying themselves with a decorum they hoped the noble Itsko Edelman would have admired.

Whether he would have or not is, of course, a matter of speculation, and as with all speculation, one that can’t be settled definitively. What we can assess instead is the true character of this Itsko Edelman, particularly when he was still known as Itsko the Pole. During the earlier census, he was just three years old. By the time the edict requiring surnames reached the town, he was twenty-three, unmarried, and living in the household of his older brother Zimel, who worked as a tailor. At the time, Slutsk was famous for its production of kontusz sashes, made of silk and worn by wealthy landowners across the region. But Zimel wasn’t particularly talented, nor was he successful enough to buy silk. Instead he made simple everyday wear for those who couldn’t afford his more skilled competitors’ merchandise. He earned just enough to feed his wife and four children and considered Itsko’s presence an unfortunate burden, a view he never refrained from sharing with anyone who would listen.

“It’s time for him to make his own way,” he would tell his wife and customers, though in the evenings, when actually faced with his younger brother, whose blue-gray eyes reminded him of their departed mother, he could never bring himself to speak these thoughts aloud. Instead, he would ask if Itsko had had any luck selling his wares — he spent his mornings carving small wooden dolls with a dull knife, and his afternoons carrying them from house to house — and when his brother gave a weary shake of his head, Zimel would feel for him a reluctant surge of pity and decide he could continue living with the family for a while longer. “You’re young yet,” he’d say, though at twenty-eight, Zimel himself already had numerous strands of gray threading his beard. “There’s plenty of time for you to find your path.”

For his part, Itsko had no interest in leaving his brother’s household. He was content sleeping in the kitchen and spending mornings in the muddy yard where emaciated chickens pecked scattered seeds and where he was out of his sister-in-law’s way. There, it’s true, he carved wooden dolls with the knife his father had given him when he was ten years old and that he remembered to sharpen only when making trinkets for his niece and nephews, whom he adored. He had skill with a blade, and a honed one might have led to finer creations and increased their value. But his dolls were good enough for the handful of children whose parents gave Itsko a few kopeks — or copper grosz left over from the days of the Commonwealth — to get him to leave their doorstep with one fewer in his sack. The weight of what remained he didn’t mind. He was a strong young man, well-built, with thick dark hair and an easy laugh. The pale eyes passed down from his mother gave him a lighthearted countenance, along with a hint of authority, as if he were a messenger from the gentiles who ruled the land. Even those who didn’t buy anything from him enjoyed exchanging pleasantries and gossip before he shuffled down the street.

But he never visited more than a few houses on any given day, because after the third or fourth, he felt an irresistible pull in a certain direction, and his steps soon led him to the house of Grinfeld, the brewer. This one was larger than most in the Jewish quarter, two stories high, with a silver mezuzah instead of a wooden one beside the front door. Itsko, however, never went through the front door. Instead, after glancing around to make sure no one was watching, he slipped around to the back, where Grinfeld’s young wife waited, still in her shift, and covered him with caresses even before dragging him inside. There was a tall wooden fence surrounding the brewer’s yard, which was twice the width of Zimel’s and covered with a fresh layer of straw. No one could see them, she had assured him. Any doubts Itsko still harbored evaporated as soon as he reached the brewer’s soft bed. There he’d spend several hours enjoying her body and beer brewed by her husband, before returning to his brother’s house in time to eat the dinner his sister-in-law had prepared for the family.

It was a blissful existence, one he hoped to continue indefinitely. But when the tsar’s decree reached Slutsk, Zimel abruptly, though with tears in his eyes, told his brother they’d have to make a change. Taxes would be determined by how many male relatives lived in a single household, and with three sons already, he couldn’t afford to keep Itsko under his care. He’d have to become head of his own household and acquire his own surname. Zimel had already appeared before the kahal and received his new name, Shneyder — the Yiddish term for tailor — an obvious choice given his trade. Of course, until he could purchase a house of his own, Itsko was welcome to sleep in the woodshed. And in a few months, when it grew too cold in the shed, he could return to sleeping in the kitchen, but that didn’t mean he was a part of Zimel’s household; he would have to be his own man from now on, though of course Zimel would always take care of him as best he could, he said, tears now overflowing, because Itsko had their mother’s beautiful eyes; but he wouldn’t be a Shneyder. In any case, Zimel went on, how could Itsko consider bearing such a name when he’d never picked up a needle and thread in his life?

It was a blissful existence, one he hoped to continue indefinitely.

Itsko left the house with his sack of dolls and a head full of confusion. Did this really change anything? In winter — or given Zimel’s generous nature, perhaps sooner— he could sleep in his brother’s kitchen once again. He could still eat his brother’s food, carve dolls in his brother’s yard, take pleasure with the brewer’s voluptuous wife. What did a name matter?

Somehow, though, the thought that he could no longer be Itsko ben Yaakov, or simply Itsko the Pole, made him feel burdened with a responsibility he didn’t understand, one far heavier than his sack. For a few days he worked harder than usual, selling and replenishing his stock of dolls with a vigor that surprised him; this was followed by a week of despondency, in which he failed to work at all. The day he was to appear before the kahal, he didn’t bother to knock on doors. Instead he wandered the streets and gazed into shops without speaking to anyone before making his way to the brewer’s house.

When he arrived, Grinfeld’s wife embraced him as usual, screamed her delight, and thanked him for his attentions. But then she told him she should no longer see him, at least for now. She had a child in her belly, she said, and since Grinfeld made love like a timid mouse, Itsko was likely the father, so it was best if he stopped visiting in case the child looked too much like him and someone should suspect.

She would miss him terribly, she said, his gentle touch and the forceful thrust of his member — which she held now, lightly, in its shriveled state — but it was time for her to grow up and become a mother, and setting aside her own needs and desires, she went on, running a finger along the ridge of his circumcision scar, was a small sacrifice to make for the sake of her child. And really, Itsko was just a silly boy with nothing to speak for him but his youth and exuberance, she added, as his member grew again beneath her hand; he had no real profession, certainly not one prestigious enough to grant him a worthy surname, and what good could come of spending afternoons with him when she had a wealthy husband who provided her with a house and finely made clothes, who would care for the child whether it resembled him or not, who would ensure they both lived a life of comfort and security, if also of dullness and mild dissatisfaction, so perhaps, she whispered, climbing atop him, one could fit just a bit more pleasure into a final afternoon of farewells. As he left, she urged him to find a vocation deserving of a name he could carry with pride. She also decided they need not be overly cautious after all and made him promise to return the following day.

But first, Itsko had to present himself at the squat annex of the Kalte Shul. It was built of rough boards and lit by smoky, flickering lamps — a contrast to the synagogue itself, the grandest building in town with its vaulted ceiling and arched windows that let light stream across the bimah. The governing council, arranged in a semicircle on a raised platform, was made up of prominent leaders from the community, among them an assistant rabbi, two leaseholders, a textiles merchant, and the brewer Grinfeld.

Grinfeld was a gaunt, red-bearded man of thirty with pockmarked cheeks and sunken eyes. How such an ugly man had obtained a young and beautiful wife — Itsko pictured her above him, an abundance of soft pale flesh, astonished eyes and gaping mouth — was no secret: he’d paid her family handsomely. Itsko tried to stir up bitterness in himself while looking at the unseemly face, but the brewer’s eyes, so sad as they gazed back at his, undermined any attempt at jealousy. If the child was indeed Itsko’s, it would be far more attractive than the father who would raise it. Or if, despite the timidity and clumsiness of the brewer’s love-making, the child turned out to be his, it would suffer for the repulsive traits he passed along. In either case, it would inherit the surname Grinfeld adopted when he lived in Prussia to learn his trade — a distinguished-sounding name, though it was perhaps pretentious to associate brewing beer with green fields.

From his heavy chair, the assistant rabbi began the proceedings by asking Itsko if he was head of a household, to which Itsko answered in the affirmative, with a twitch in his eyelid he couldn’t fend off. He tried to picture himself in a house of his own, with a plump wife boiling beef, but the image kept blurring whenever he added to it a detail of himself returning from work at a trade for which he had no skill or ambition. The truth is, he had never desired a life like his brother’s or his father’s, one that led to cramped hands, a bent back, and underfed children. What he wanted instead he couldn’t have named, though when he tried to imagine it, with a longing that occasionally pained him, he saw it taking shape only beneath his knife, since that was the tool he knew best. The textiles merchant asked how he made his living, and he mumbled some words about carving and dolls. But this only seemed to irritate the merchant, who said, with impatience, “We can’t name you for a toy.”

He tried to picture himself in a house of his own, with a plump wife boiling beef, but the image kept blurring.

“We can call him Luftmensch,” said one of the leaseholders, laughing and looking to his companions for approval. “Since he’s so practical.”

“Or Megege,” said the other, offering the Yiddish word for dawdler. He was stone-faced and spoke without inflection, which Itsko found funnier than the joke. He couldn’t keep himself from tittering along with the others, all except the brewer.

“Don’t poke fun at the boy just because he’s less fortunate than we are,” said Grinfeld, an uneasy pleading note in his voice.

“We can call him Schvartz,” the assistant rabbi said. “He’s dark enough.”

“We’ve got three Schvartzes already,” said the merchant, whose impatience suddenly dissipated. He reclined in his chair as if it were Passover and he had all the time in the world to make a decision. “And they’re all darker than this one.”

“He’s strong and healthy,” Grinfeld said meekly. “Let’s give him a name that suits his stature.”

“We’re not calling him Breytman,” said the merchant. “While he might be broad, a name like that would require some … charitable donation to the shul.”

“Perhaps Libhober,” the stouter of the leaseholders said — speaking the word for lover — and the slimmer one laughed a wheezing laugh. The merchant leered. The assistant rabbi let out a sigh. Grinfeld looked as if he would soon begin weeping.

The brewer muttered, “He’s a man of good quality. He should be treated with respect.”

Itsko held his uncertain smile until it hurt. Did he understand what he was hearing? Was his secret truly shared by all? Why, then, would the brewer, knowing what he’d done, come to his defense?

The stout leaseholder whispered something Itsko couldn’t hear, and this time no one laughed. The beams of the shul annex seemed to sag overhead. He smelled his sweat and that of the brewer’s wife, which was both sweeter and more pungent. He wished he had a sip of the brewer’s wares to slick his dry throat.

“He wouldn’t wrong someone,” Grinfeld insisted, as if trying to convince both of them, or make it so. “Not on purpose.”

The members of the kahal shifted in their seats, but no one objected. Words of self-reproach passed through Itsko’s mind, along with promises to cease his visits to the brewer’s wife, to live up to the quality the brewer believed, or wanted to believe, he possessed — a quality that might be passed to the child the brewer would raise as his own. But the words stopped before reaching his mouth. He stood with his head lowered, his eyes focused on the ragged seam between two floorboards. He set his feet a short distance apart, clasped his hands at his waist, and waited. Whatever punishment he might receive would have to arrive from somewhere higher than the short platform on which the committee sat. Anything he said now would only cause further injury, he decided — to himself, if not to the brewer.

“In his heart,” Grinfeld whispered, with a desperation now that made Itsko want to assure him he was speaking the truth, “he’s noble.”

“Fine,” the assistant rabbi said quickly, jotting down a note in his ledger. “We’ll call him Edelman.”

Grinfeld tilted his head back and closed his eyes. The other members of the kahal made sounds of relief, the merchant turning his attention to a loose thread on his sleeve, the leaseholders straightening their backs as if readying themselves for a new task. Itsko, not knowing what he should do next, stood in place, hands gripped against his middle.

Were they mocking him still? Or had the brewer in fact glimpsed something in him that he himself had never seen?

Through a haze of puzzlement, he could remember a morning several months past, when his little niece Toiba, Zimel’s youngest, begged him to carve a new doll. Her eager smile demanded something more than his usual carelessness, and before beginning he told her that first he had to sharpen his knife. The blade then seemed to move of its own accord, discovering a face hiding in the wood, his hand guided by something more urgent even than the girl’s excited cries.

“What are you waiting for?” the assistant rabbi said, peering at him. “Go be noble.”

Illustration by Jenny Kroik

“What are you waiting for?” the assistant rabbi said, peering at him. “Go be noble.”

With a name like that, gifted so unexpectedly, what could Itsko Edelman do but leave the shul and seek out a virtuous life?

Whether he found such a life or not, the census doesn’t indicate. But from the historical record, we know that he eventually fathered legitimate children who carried his name forward into the world, with the belief that they deserved it, along with their nimble fingers and dark hair and gray-blue eyes. Those features found their way into the Grinfeld line as well, and though some of the Grinfelds might have been more apt bearers of the Edelman name than their own, all of them remained modest about their place in the world, identifying only with the fields that sprouted green at winter’s end.

Two generations later, in any case, a Grinfeld daughter married an Edelman son, and the lines recrossed, the qualities — inherited or learned — blended together until the descendants were all equally dignified and humble, just like the sad brewer who endured a moment’s agony in hopes of a better future.

And the future was generally better, at least for those of his people who, not quite a century later, emigrated when they had the chance and lived their upstanding lives in a land across the sea.

Less so, we’ll acknowledge, for the boys sent to their death in the Crimea. And also, of course, for those who chose to stay when their brethren left for America and still lived in their unassuming homes when Einsatzgruppen marched into their city in the autumn of 1941, firing thousands of bullets that erased all memory of Edelmans and Grinfelds and Shneyders from the narrow streets of Slutsk.

Scott Nadelson is the author of a novel, a memoir, and six collections of short fiction, most recently While It Lasts.