Ruth Bader Ginsburg, U.S. Supreme Court justice, 2006.

Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States, Photographer: Steve Petteway

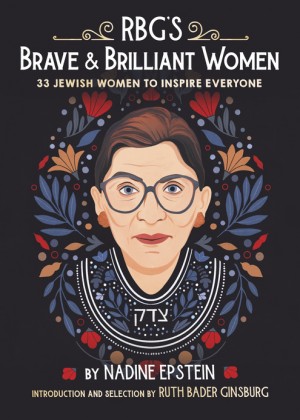

People always ask me how Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg and I chose the women featured in our collaboration, RBG’s Brave and Brilliant Women: 33 Jewish Women To Inspire Everyone. After all, there have been and continue to be so many amazing Jewish women — what were the criteria in selecting our very eclectic group?

I just took a peek at my early notes for the book and the criteria went something like this: “A woman who defied the stereotypes of her time to be a pioneer or amazing success in her field or who saved people, made discoveries or created positive change in the world. She refused to be defined by the expectations and limitations of her time. Her path paved the way for the advancement of women and/or influenced the trajectory of the Jewish people and/or all people. She was not male-defined. She was not only a good and patient wife, a martyr, or a victim. She was a woman whose life and achievements, in the face of gender discrimination and other obstacles, we can learn from and be inspired by today. She was and is a role model.”

There are, of course, countless women over time who could fit these criteria!

The book was born out of a conversation in Justice Ginsburg’s chambers, and in fact, the selection process began the moment we decided to collaborate on it. We were sitting in Justice Ginsburg’s exquisitely decorated rooms, surrounded by art she had collected, photographs and awards. The Justice immediately began listing the names of women who she said had inspired and sustained her through difficult times.

“Anne Frank,” she said.

“Henrietta Szold.

“Emma Lazarus.

“Deborah.

“And we have to include the five women of the Haggadah — Miriam, Moses’ mother, and the two midwives. And of course, Pharaoh’s daughter.”

“Pharaoh’s daughter?” I asked, a bit taken aback. “Was she even Jewish?”

“It doesn’t matter,” said the Justice. “She was one of the women of Exodus who helped save the Jewish people. Without her, without them, Moses would not have grown up to lead the Israelites out of Egypt.” I later learned of the traditions that teach that Batya, Pharaoh’s daughter, married an Israelite and left Egypt with the Israelites.

Many worthy women have been lost to the shadows of history, which until recently was almost exclusively recorded by men. Documentation was scarce.

That afternoon, Justice Ginsburg also mentioned Rebecca Gratz, Lillian Wald, and Golda Meir, as well as her friend Gloria Steinem.

She had other duties to attend to that day and so did I, so we agreed I would do some research and come up with more names of women to discuss. I did. It was tremendously satisfying work but no easy task. Many worthy women have been lost to the shadows of history, which until recently was almost exclusively recorded by men. Documentation was scarce.

Meanwhile emails from the Justice with new names kept arriving in my inbox.

Nadine Gordimer.

Simone Veil.

Rita Levy-Montalcini.

Finally, we came up with a group of about 150 diverse women spanning ancient to contemporary times. Then, for reasons of time and space, we had to narrow the list down. In the end, we were back to the women who most fascinated the Justice. Some had inspired her as a girl and a young woman, such as Gertrude Berg and Roberta Peters; others she had read about or met as an adult, such as the groundbreaking labor lawyer Bessie Margolin; Muriel Siebert, the first woman to purchase a seat on the New York Stock Exchange; and Levy-Montalicini, who received the Nobel Prize for medicine. The Justice graciously gave me space to suggest a few women who inspired me: the Judean Queen Salome Alexandra; the sixteenth century Portuguese shipping magnate Gracia Mendes Nasi, who saved Jews from the Inquisition; Rosalind Franklin, the scientist who identified the structure of DNA; among others. In the process, both of us discovered and learned about women we hadn’t known about before.

You might ask: There are so many great women, why focus on Jewish women in particular? It’s a good question. Part of me longed to open up the field and include women such as Frances Perkins, the first American woman to be named to a presidential cabinet, and the brilliant Eleanor Roosevelt. But at its heart, the book was filling a hole for both of us. Although we were from different generations, we were giving life to the book we had once longed to find on the library shelf, the book that would have made our childhood Jewish educations more meaningful.

In fact, it took me awhile to understand just how important the Jewish women in this book were to the Justice. They were part of her personal Jewish journey — a journey that began when she was an elementary school student who dutifully absorbed her Torah lessons, then a teenager who was confirmed by her synagogue. That segment of her Jewish journey, however, came to an abrupt end when her mother, to whom she was very close, died. At sixteen, the Justice knew the prayers and wanted to say them as part of the minyan at the shiva but was excluded from doing so because she was a woman. That experience, at a very vulnerable moment in her life, led her to reject the traditional patriarchal Judaism of her youth. She remained deeply Jewish — living by Jewish values — but her Judaism became manifest in her passion, even hunger, for the stories of great Jewish women.

If only we could have fit in every woman who inspired us! Here are a few whom we couldn’t fit in to the book. Gloria Steinem, for instance: It was simply too jarring to include a living woman amid women of history, and we concluded that she might fit better in a follow-up book. Some women the Justice admired, such as Dorothy Parker and Bess Myerson, had lives too complicated to easily fit into an intergenerational book. For lack of time and space I had to let go of a few of my personal favorites: the pre-Israel spy Sarah Aronson, the pioneering surgeon Fanny Berlin, and Seraphine Epsteinn Pisko who in 1911 was appointed to lead the National Jewish Hospital in Denver. I also would have liked to include the brave journalist Ruth Gruber, who not only covered some of the most important stories of her time but also helped save Jewish refugees during World War II. I met and spoke with her several times before she died at 105 in 2016.

And so, in the end, we chose thirty-three women. We were aiming for thirty-six, double chai, but ultimately we ran out of time. I miss the presence of the women we couldn’t include and, most of all, I miss the book’s true star — Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg. I hope she would have taken great pleasure in seeing the book in its finished form and in knowing that the stories of these brave and brilliant women are now part of her legacy. I know how strongly she believed that their stories deserved as much attention as possible, and would continue to inspire so many more!

Nadine Epstein is an award-winning journalist and editor-in-chief of Moment Magazine. She is the founder of the Role Model Project, created in memory of Justice Ginsburg to help young people identify and select role models. Epstein lives in Washington, DC.