Erica Lyons and Bonnie Pang’s new picture book presents young readers with a little-known part of Jewish history. When Nazi oppression descended on Europe’s Jews, some found a temporary refuge in Shanghai. Lily’s Hong Kong Honey Cake includes information about this process in an afterword. The story itself focuses on one fictional child and her family, who abandon their home and bakery in Vienna, traveling far away to an unfamiliar land and culture. As conditions in China worsen, their Rosh Hashanah celebrations become more diminished by poverty. Yet, with each year of their exile, Lily’s mother reinforces the sweetness of their traditions. Warm images of family life emphasize how Jewish culture was able to take root under the most adverse circumstances.

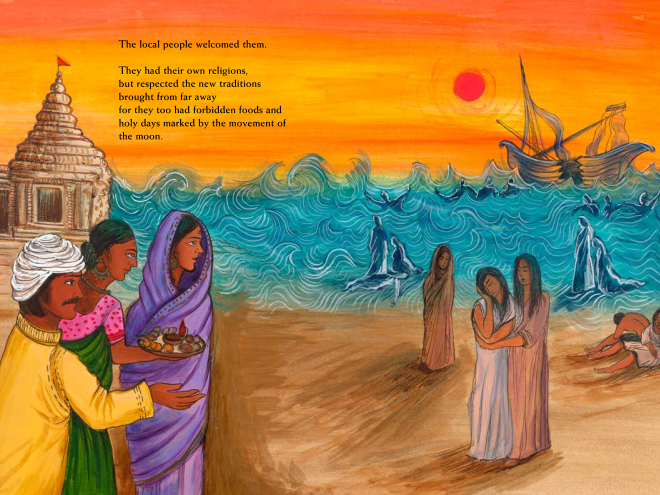

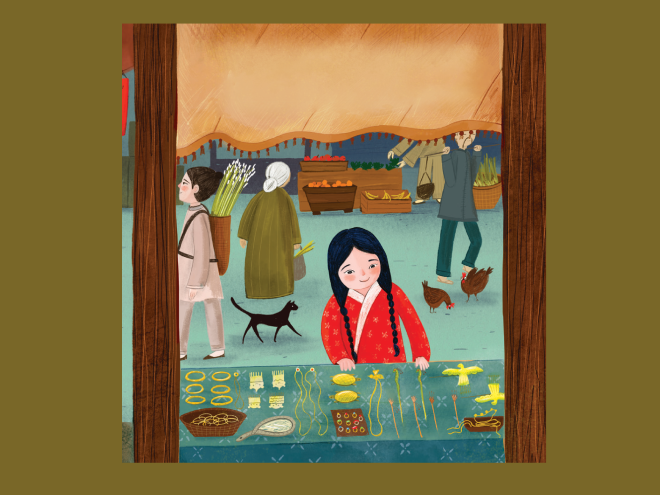

The book opens with Lily’s mother managing her business while keeping her baby girl at her side in a bassinet. Combining the elegance of pastries “wrapped in pink paper, delicate like a butterfly’s wings,” with the support of their whole community, the bakery embodies an idyllic atmosphere before everything changes. Lily’s excitement about the upcoming move contrasts with the despair of adults, which is initially hidden. Her mother feeds her honey cake onboard the ship for China, repeating her reassuring phrase, “For a sweet year, my sweet one.” Pang’s illustrations evoke the family’s enthusiasm about offering their products to welcoming neighbors. Store signs in Chinese and the noodle shop next door may seem exotic, but the customers who line up for honey cake aren’t very different from those they knew in Vienna. The cake’s sweetness melds with “smoke from the neighbor’s incense,” as they gather together, listening to Papa’s nostalgic stories.

An ugly reality encroaches on each ensuing New Year in Shanghai. Lyons’s subtle selection of details allows young readers to glimpse a world at war. Rice substitutes for flour and the newspapers wrapping their cakes are “filled with pictures of war.” By Lily’s eighth celebration of Rosh Hashanah, the honey cake has disappeared entirely. But the war ends, and a two-page spread depicting the family’s voyage by ship to Hong Kong is an iconic image of emigration and hope. Observing the holiday in a formerly grand hotel, the Jewish refugees have access to a Torah and prayer books. What more would they need? Lily’s now engrained habit of adaptiveness leads her to take a bold step. She approaches the hotel’s kitchen staff, and, with the essential ingredients of their kindness and empathy, the honey cake returns.

Lily’s Hong Kong Honey Cake is highly recommended and includes an afterword, a glossary, and a map.

Emily Schneider writes about literature, feminism, and culture for Tablet, The Forward, The Horn Book, and other publications, and writes about children’s books on her blog. She has a Ph.D. in Romance Languages and Literatures.