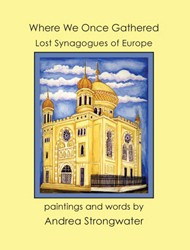

Lost Synagogues of Europe is a beautiful tribute to the roughly 17,000 synagogues destroyed by the Third Reich and Communist ideologues. With their destruction, records and visual information were also destroyed. Andrea Strongwater, an artist and author, has created elaborate portraits of seventy-seven synagogues about which enough illustrative and documentary information survives to tell their story and the story of the communities they served.

Jews had always lived throughout most of Europe, but before the seventeenth century they were usually required to worship in secret in segregated quarters. The chronological organization of this book follows the slow entry of Jews into the greater European society. The first portrait is of the Livorno Synagogue, constructed in 1603; the newly expanding Tuscan port city welcomed foreigners, including Jewish ones. From then until the mid-eighteenth century, construction of synagogues was intermittent. The other synagogues of this period are usually modest, some constructed of wood. A singular example of synagogue architecture is in Bad Buchau, where the Christian builders copied the style of the local church.

Most of the synagogues in the book were built after 1860, reflecting increasing acceptance of Jews. Restrictions had begun easing toward the mid-seventeenth century and after the French Revolution; by the mid-nineteenth century, Jews felt secure enough to take a more active place in society and to erect public synagogues that reflected their pride and prosperity. The synagogues of this period are more elaborate than most earlier synagogues, and were often built in the Indo-Saracenic style popular in Europe. The style also recalls connections to the Middle East and Sephardic communities.

The synagogues illustrated here were concentrated in central and eastern Europe, the majority in Germany. They were prominent buildings, important enough to appear on postcards and photographs, the documents on which Strongwater based her paintings. They have to stand in for the many smaller synagogues across Europe that also suffered destruction during World War II and the Soviet period. In a few instances returning or small existing communities have constructed new synagogues, but most of the synagogues in the heart of Europe exist only as plaques or plazas erected in their memory.

In an informative foreword, Ismar Schorsch, chancellor emeritus of the Jewish Theological Seminary, follows the development of the synagogue from the sacrifice-oriented priest-led worship in the Jerusalem Temple to a teaching center dedicated to study of the Torah — thus replacing the sanctity of place with the sanctity of the book, a book that has to read in a community of ten men. With the flourishing of the synagogues featured in this book came another change of worship style, a style influenced by church decorum and rabbinic and cantorial leadership. The widespread destruction of these synagogues, so lovingly portrayed in this book, once again led to change in style as the establishment of Israel led once again to more communal worship.

Lost Synagogues of Europe revives a moment in history when Jews began to take their place in European life only to be cruelly cast out. To show the extent of the destruction, Strongwater includes a map indicating the location of each illustrated synagogue and a listing of synagogues by country.

Maron L. Waxman, retired editorial director, special projects, at the American Museum of Natural History, was also an editorial director at HarperCollins and Book-of-the-Month Club.