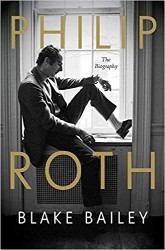

Steven J. Zipperstein’s biography portrays Roth as, first and foremost, a writer. Philip Roth: Stung By Life draws on the places Roth lived and visited, as well as his friends, family, lovers, and rivals, in order to create the works in his extensive oeuvre. Highlighting points of intersection between Roth’s life and writing — gleaned from archival materials, interviews, and memoirs of those who knew him, as well as interviews with Roth himself — Zipperstein generously narrates the life of a titan of American letters.

Roth was born in Newark, New Jersey, which boasted a bustling Jewish immigrant community and the site of several of his most celebrated works. His parents, Bess and Herman, loom large in his work. Roth’s Patrimony: A True Story (1991) is a touching memoir of his father’s illness and death. Zipperstein writes that a scene in Portnoy’s Complaint (1969), in which the eponymous onanistic narrator’s mother threatens him with a knife for not finishing his meal, was based on an episode involving Bess. The biography shows how Roth’s travels abroad, including trips to Prague (during which he met writers from the “other Europe” whose work he championed), to Israel, and the years spent in London with his second wife, Claire Bloom (whose portrait of Roth in her Leaving a Doll’s House (1996) Roth felt cost him the Nobel Prize), informed his work.

Just as importantly, writers, including the angst-ridden Franz Kafka, the novelist Henry James, and the playwright William Shakespeare, are touchstones in Roth’s writing. The ever-sensitive Roth was deeply wounded by Jewish critic and novelist Irving Howe’s scathing 1972 Commentary essay “Philip Roth Reconsidered.” In the wake of Howe’s critique, Roth began publishing novels featuring his alter ego, Nathan Zuckerman. The first was The Ghost Writer (1979), in which Zuckerman imagines a fictional novelist, E. I. Lonoff, having a clandestine affair with Anne Frank. Jewishness as a form of cultural and identity, rather than normative halakhic Judaism, is significant in Roth’s work, which is permeated by Jewish politics and family dynamics. Just as importantly, Roth’s work touches on race relations, the sexual revolution, and nearly every significant cultural trend in postwar America.

Sexuality and the objectification of women, including a matter-of-factness about infidelity, is prevalent in Roth’s work as well as Zipperstein’s biography. Zipperstein highlights Roth’s sexual avariciousness and the pulchritude of his many paramours. Although some readers may find this objectification gratuitous, it is true that Roth based many of his famous female characters on women he knew. Drenka from Sabbath’s Theater (1995), for example, was based on his physical therapist, Maletta Pfeiffer, with whom had an extended affair. Zipperstein’s engagement with Roth’s sex life is used to show the creatively generative connection between Roth’s life and art.

Brian Hillman is an assistant professor in the Department of Philosophy and Religious Studies at Towson University.