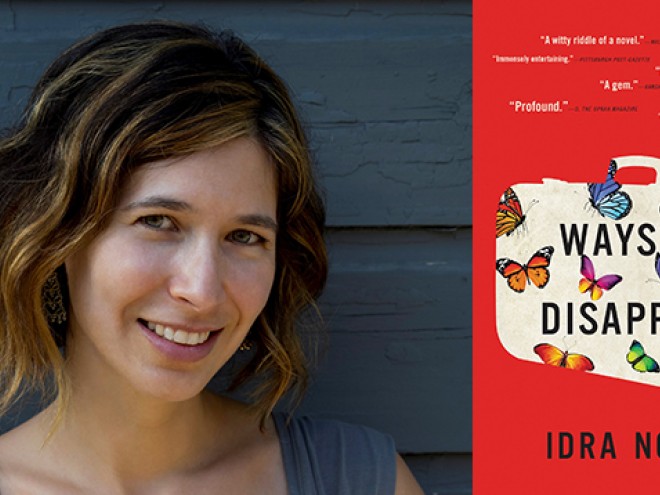

Idra Novey’s Soon and Wholly examines a variety of topics: the speaker’s childhood home in Appalachian Pennsylvania, Jewish Brazilian author Clarice Lispector, the loneliness epidemic, and Erica Baum’s collages. What connects these topics is connection — the human need for it across region, medium, and language. Soon and Wholly survives our “newest continuous disaster” by finding equally new ways of relating across distances, be it through experimental syntax (“If the matter with the clatter of earrings is.”) or by taking a road trip just to harvest rhubarb planted by an ancestor. The author’s inclusion of female Jewish Appalachian and Brazilian experiences also make it a collection that does the important and often neglected work of connecting the lives of Jewish women across time and place.

The book begins with the standalone poem “Nearly,” a catalogue of “almosts” and “near misses” brilliantly presented in dependent clauses — “near”-sentences. The rest of the book is organized into four sections, each of which contains a series that explores connection through its themes as well as the connection inherent in the series as a form. Some of these series document isolation — “O Earth: An Estrangement in Six Parts” is a meditation on climate denial and technological isolation and “Too Soon To Tell” is both a pandemic poem and an ekphrastic response to Erica Baum’s collages, which pair Baum’s long strips of paper and newsprint with Novey’s long sentences. While these series document loneliness, others, such as “Regarding Marmalade, Cognates, and Visitors,” are peopled with houseguests. Two series are written as epistolaries: “Letters to C” is a series of letters Novey writes to Lispector while translating her work, and “Housesitting with Approaching Fire” follows a speaker who cannot avert ecological disaster because “what can a poet in a borrowed house really offer in a spreading fire?/Maybe a few remarks on the art of denial.” These series depict a society where we can no longer connect to each other, our bodies, or nature. In place of connection, we “suck in some Twitter” and “mock-race over fake grass” while mourning that “we were close/as cognates once, nearly holy/to one another.”

The collection’s exploration of Appalachia serves as a contrast to contemporary cultural hegemony. In the first glimpse of Appalachia in the book, we see the speaker’s foot sinking into “the rotting chest wall of dead deer,” before which she “hadn’t considered how the unknowable might get a hold of me.” “The Duck Shit at Clarion Creek” recalls the polluted creek where teenagers from the speaker’s hometown would go for romantic encounters, a creek so symbolic of connection they sensed the creek bed “would claim us, hold us hard and close.” “That’s How Far I’d Drive For It” documents a trip back to the speaker’s childhood home to harvest rhubarb from a patch planted by an ancestor “who didn’t begin her life here, never learned to write in English, yet still managed to plant something that perennially thickened, red and edible.” When the speaker and her friend Helen reach the general location of where the rhubarb should be, they realize they are lost, but no one is around to ask for directions. Helen suggests “maybe a fellow human would appear if we play better music.” So they “belted Tina Turner and it worked: we found humanity — a woman exiting a house, a man behind her with a stripe of hair like a skunk tail.//‘These are the people,’ Helen said. ‘They will know what we need to know.’” “On Returning to My Hometown in 2035” imagines how ecological destruction will destroy even places already destroyed by deindustrialization: “Even the gun shows are gone now, even the scrapyards, the darkest, farthest barns.//The strip mall, half-empty since my elementary years, contains only chemicals now.” The collection ends with “Afterlife,” in which the speaker remembers imagining turning into “a tree with no feelings except in seeds and shadows” in order to survive the pain of existence.

Soon and Wholly is a book that fights its way back to human connection — a book that commands us to remain open because “To answer yes to someone in the dark, even to yourself, has the faint sound of color.” The collection celebrates the smallest victories of reclaiming our humanness, reminding us to claim our selfhood before technology does: “Exercising your iris sends a message to your mind: it is not yet made of vinyl.//Your eyes still have a calling: they strain for light.”

Allison Pitinii Davis is the author of Line Study of a Motel Clerk (Baobab Press, 2017), a finalist for the Berru Poetry Award and the Ohioana Book Award.