Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

Earlier this week, Gerald Kolpan shared the story behind Eli Gershonson, a photo gallery of some of the historical figures in his novel, and the story behind how he came to write Magic Words. He has been blogging here all week for Jewish Book Council and MyJewishLearning.

When a modern audience thinks of American Indians and American Jews, the image that comes to mind is likely to be that of Mel Brooks as an Indian chief in Blazing Saddles.

When a modern audience thinks of American Indians and American Jews, the image that comes to mind is likely to be that of Mel Brooks as an Indian chief in Blazing Saddles.

Dressed in ornate plains schmattes (including war bonnet), and astride a paint pony, Brooks and his warriors come upon a prairie schooner carrying an African-American family. “Chief” Brooks looks at the little group as they huddle together in terror, and then turns to his closest companion who is raising his tomahawk to strike:

No, no, zayt nisht meshuge! Loz im geyn! Abi gezint! Take off! Hosti gezen in dayne lebn? (Don’t be crazy! Let him go. As long as you’re healthy! Take off! Have you ever seen such a thing?).

The “chief” lets the family go in peace, quickly stating the reason for his mercy:

“They darker than us!”

It’s either funny or offensive depending upon who’s watching; but for many, it’s the only reference to Jews and Indians they’ve ever seen.

Pity — because there was a bone fide Jewish Indian chief. His is a tale of guts and brains, as are most stories about Jews among the Indians.

Almost from the beginning of Westward expansion, Jews have made a home on the range. They were fur trappers, gold miners, cowboys, peddlers and scouts. There were sheriffs, marshals, mayors of small towns and at least one gunfighter. A shana medele from San Francisco married Wyatt Earp; a storekeeper from Bavaria and a tailor from Latvia invented blue jeans.

Czechoslovakian émigré Sigmund Schlesinger was one such pioneer. After losing his job in Philadelphia, Schlesinger went to eastern Kansas where he found work on the railroad, only to be laid off again when hostile Sioux took charge of the tracks. Needing work, he volunteered to be an Indian Scout for the Army, despite never having ridden a horse or shot a gun. A quick study, he became a hero of the Battle of Breecher’s Island, Colorado, said by some to be the most ferocious in the history of the Indian Wars.

Years after the battle, his commanding officer wrote to Rabbi Henry Cohen of Galveston, Texas:

He had never been in action prior to our fight with the Indians and throughout the whole engagement which was one of the hardest, if not the very hardest, ever fought on the Western plains, he behaved with great courage, cool persistence and a dogged determination that won my unstinted admiration as well as that of his comrades, many of whom had seen service throughout the War of Rebellion on one side or the other.

I can accord him no higher praise than that he was the equal of many in courage, steady and persistent devotion to duty, and unswerving and tenacious pluck of any man in my command.

But not all Jews encountered the Indians in battle. Some were among their closest friends – and became trusted advocates for their rights and freedoms.

Such a man was Julius Meyer, the hero of my novel Magic Words, born in Bromberg, Prussia in 1851.

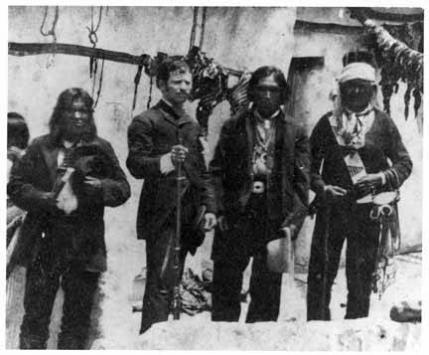

Julius Meyer

Meyer came to the United States in 1866. In Europe, he had been a yeshiver bocher and a talented musician. Shortly after his arrival, he joined his older brothers Max, Adolph and Moritz in Omaha where they had a prospering cigar and jewelry business. Separate from his brothers, Julius began trading with Indian tribes like the Ponca, Omaha, and Sioux. So well known did he become for his honesty that the Indians dubbed him “Box-Ka-Re-Sha-Hash-Ta-Ka: “the curly-headed chief who speaks with one tongue.”

According to Julius, in 1869, a hostile tribe attacked him. They tried to kill him – and it was only the intercession of Standing Bear, chief of the Ponca, that saved his life. Julius became Standing Bear’s interpreter and was soon translating for such famous chiefs as Sitting Bull, Red Cloud, and Swift Bear.

For many years, Meyer served as Omaha’s government Indian agent, often fighting for Native rights. Julius was also known as a man who knew how to make a dollar for his friends (and himself). One such scheme involved taking Standing Bear and a group of the Ponca on a yearlong jaunt to the 1889 Paris Exposition where they caused a sensation.

Julius kept up his association with Standing Bear and the Nebraska tribes until May 10, 1909 – the day he was discovered dead in Omaha’s Hanscom Park. He was clutching a revolver and had two bullet holes in him: one in his temple and another in his chest. He was legally declared a suicide, although to this day, there are people who believe that this great Jewish friend of the Indian was murdered.

Still, if Julius Meyer was an honorary Indian, Solomon Bibo became the real thing: real enough, in fact, to become a chief.

Bibo was born in Westphalia in what is now Germany, in 1853. Like Meyer, he immigrated in 1869 and joined his brothers in business. The Bibos were among Santa Fe, New Mexico’s most successful traders, known for square dealing with their Indian neighbors. Bibo and his brothers became speakers of several Indian dialects and Solomon was often called upon by the Acoma Pueblo to negotiate treaties between their tribe and the U.S. government.

In 1885, Bibo married Juana Valle, the granddaughter of an Acoma chief. Later that year, the Acoma elected Bibo their new “governor,” the equivalent of tribal chief — a position he held four times. He helped create the tribe’s first modern education system, hired its first schoolteacher and supervised the first Acoma school building.

Solomon Bibo

Solomon and Juana were married for nearly fifty years and had six children. Years before, she had converted to Judaism. At 13, their son, Leroy became a traditional Bar Mitzvah but also participated in the Acoma rituals of manhood. The couple was separated only by his death on May 4, 1934; they are buried side-by-side in a Jewish Cemetery in Colma, California.

Visit Gerald Kolpan’s website for more about Magic Words and his first novel, Etta.

Gerald Kolpan’s newest novel, Magic Words: The Tale of a Jewish Boy-Interpreter, the World’s Most Estimable Magician, a Murderous Harlot, and America’s Greatest Indian Chief, is now available.

Photo Gallery: The Historical Figures in Gerald Kolpan’s Magic Words