Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, Berlin, Germany. Tony Webster / Wikimedia Commons

In the not-too-distant future, the Holocaust will have passed from living memory. There will be no survivors left to tell us of the horrors they endured, or the triumph of survival, or even the mundane minutiae that is so rarely acknowledged. What they will have left behind is, of course, extraordinary. In volume. In breadth. In depth. Countless words, many of them assembled into great works of literature, others into more modest efforts, written down so that their families might know. Thousands upon thousands of hours of audio and video testimony, pictures, diagrams, photos, ephemera of the most varied kinds. Soon, however, it will all begin to gather dust, to fade into history. It will become a setting, a context, just like every other historical catastrophe. If this idea offends you, I’m glad. It offends me too. But only because it is the one horror that I have truly known, that has befallen people I have loved. I cannot separate my own connection, my need to desperately cling to its importance, from the inevitable effect of time.

I often wonder about the shape of Holocaust memory in a post-survivor world. In particular, I question the role of the novelist in keeping memory alive. Fiction has always had its place alongside memoir and nonfiction when it comes to telling stories about the Holocaust. Even in the survivor generation, for every Primo Levi or Viktor Frankl, there was an Aharon Appelfeld or Imre Kertesz. Later, fiction became a way for the children of survivors to confront the trauma that had rendered their parents silent. The third generation, with the benefit of time and an enormous ocean of primary sources, could search for essential truths that the historical record alone could not hope to convey. So too, writers with no personal connection at all. But the one thing that anchored all of them — access to firsthand accounts that are not frozen in form or substance — will soon disappear. No longer will writers be able to speak with survivors, ask questions, clarify. This might all seem obvious, but it is also critically important because what is at stake is the future of Holocaust narrative.

Nowhere has this been more apparent than in the recent controversy surrounding The Tattooist of Auschwitz, an international bestseller based on “the incredible true story” of Lali Sokolov. Its author, the Australian Heather Morris, has long maintained that the novel is “95% fact,” but it has become increasingly apparent that she took considerable liberties with the story. Sokolov’s family is said to be dismayed by Morris’s portrayal. But more telling was the response from the Auschwitz Memorial Research Center. In an unprecedented move, the Center has come out against the book and its distortion of the realities of the camp. It even went so far as to publish a fact-checking report, which refutes many of Morris’s descriptions and historical observations. The Center’s press officer ultimately concluded, in an interview with The Australian, that The Tattooist of Auschwitz is “almost without value as a document.” Another leading Holocaust scholar called it “a sex story of Auschwitz that has very little historical accuracy.”

Of course, this is not the first time that such a fuss has been made about a successful Holocaust novel. Similar accusations were leveled at John Boyne’s The Boy In The Striped Pajamas. Like The Tattooist of Auschwitz, Boyne’s book — which tells the story of a young Jewish boy who befriends the son of the camp commandant — was accused of minimizing and sanitizing the Holocaust. Even the U.K‑based Literary Review, about as un-Jewish a publication as you could imagine, devoted an entire editorial to its problematic nature. But Boyne had his supporters, too. For the most part they pointed to the book’s allegorical, almost fantastical nature. It was a kid’s book, after all, and its value lay in its message, not its fidelity or otherwise to the historical record. That has been the line taken by Morris and her publishers: a novel does not claim to stand in place of history. The Tattooist of Auschwitz is fiction, and popular fiction at that. Sounds logical, I guess. But is there not an ethical obligation, no matter how fantastical your story, to get the basic facts right?

Leaving aside Morris’s claim about her book being only 5% removed from truth (despite multiple critical departures from Sokolov’s Shoah Foundation testimony, which it would appear she never watched), the real problem with The Tattooist of Auschwitz is not that it gets Lali’s story wrong but that it gets Auschwitz wrong. Very wrong. And given its success, the version of Auschwitz it describes risks becoming dominant in the historical narrative, especially at a time when studies show that general knowledge of the Holocaust is at an all-time low and falling.

So, if distortion is already a growing phenomenon, where does that leave the Holocaust novelist? What happens when there are no survivors left and the Holocaust exists, in the creative sense, as just another historical setting? One thing is for sure. It will continue to be fertile ground for fiction. As one English bookseller said to me, “Put in a few Nazis, it’s sure to shift units.” Holocaust narrative will also drift ever further from Jewish “custodianship.” Some detractors of both Morris and Boyne have pointed to their not being Jewish as part of the issue. They are, in my mind, wrong. While #OwnVoices (a term coined to highlight marginalized characters written by authors who are part of that marginalized group) has rightly sought to rectify the silencing of underrepresented minorities in literature, it does not preclude participation from outside the Jewish writing world. In fact, two of the best Holocaust novels of recent times were written by non-Jews: Daša Drndić’s Trieste, and The Zone of Interest by Martin Amis. Drndić’s book, in particular, stands out for its meticulous research, intellectual ferocity, and eminent readability. I asked Drndić some years ago why, though she wasn’t Jewish and was from Croatia, a country with its own, more recent genocidal history, she chose to write about the Holocaust. Her response: the Holocaust is the universal symbol of barbarous inhumanity. Drndić used it as an indictment against our collective failings, to rub our noses in the worst our species has to offer. I would suggest, as a logical extension, that the Holocaust allows for the deeper exploration of themes because it carries with it a degree of assumed knowledge; you needn’t labor yourself with describing the atrocities. This allows you space that other genocides — those that might require you to write the story of the genocide, as opposed to writing a human story within it — do not.

And those are precisely the kind of stories we, as novelists, seek to tell. Not having to write the Holocaust, not having to document atrocities (itself problematic as many books tip into the realm of atrocity porn), sets us free. We can move away from the victim/hero archetype that has plagued much of Holocaust literature and return agency to those who lived through it. We can tell small stories, stories of relationships. We can confront taboos, crack open the silences. And we can do it without pages of didactic exposition.

Assuming knowledge, however, also carries considerable risk. It can breed complacency in both the reader and the writer. It can entrench errors and mistruths. And so it is incumbent upon writers to ground themselves in deep knowledge of any aspect of the Holocaust about which they write. Research, cross-check, question. All the more so if, like Morris, you are turning a survivor’s story into a novel that you will be passing off as “95% fact.” Trauma and time do terrible things to memory. Seeking to corroborate, to correct, is the ultimate act of respect, not some cynical surrender to doubt. Lali Sokolov deserved better than to have his story left open to questioning and criticism. His lapses can easily be accounted for. Morris’s cannot.

That said, I don’t mean to be proscriptive. We need not place limits on the creative endeavor. Indeed, some of my favorite Holocaust novels venture into the surreal, the hilarious, the speculative. Ladislav Fuks’s Mr. Theodore Mundstock, a forgotten classic of postwar Czech literature, centers around an old man who decides to prepare himself for the concentration camps by building a replica barracks in his apartment. Mundstock is both Chicken Little and practical sage, with a touch of Jakob the Liar. That he is accompanied throughout by his shadow and an imaginary bird (both fully realized characters), allows the reader considerable insight into a mind torn between despair and unbridled optimism. Similarly, The Dance of Genghis Cohn by Romain Gary hilariously tells of a prankster who, at the moment of his execution, flashes his buttocks at a Nazi firing squad and returns as a ghost to haunt the man who shot him. And then, of course, there is Shalom Auslander’s outrageously funny Hope: A Tragedy, in which the protagonist finds himself embroiled in a battle of wits with an elderly Anne Frank who, it so happens, is living in his roof and suffering one heck of a bout of Second Book Syndrome. Novels like these may do all sorts of strange things with the Holocaust narrative as we know it. They self-consciously depart from “the facts.” But they don’t pass off inaccuracies as historical record.

And therein lies the moral. Create, create, create. But do so from a place of knowledge, and always speak the truth.

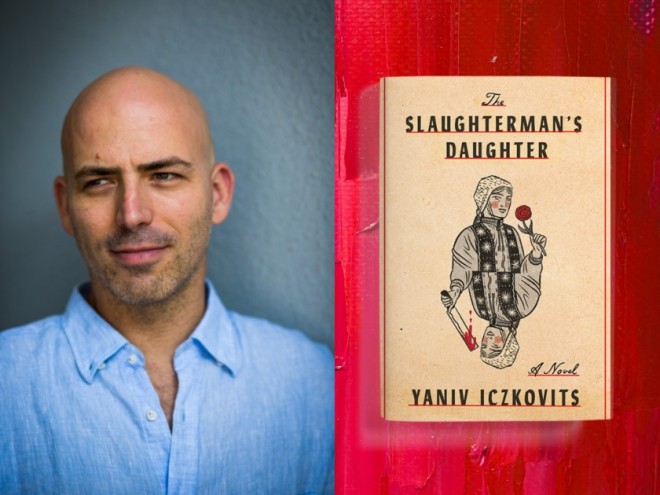

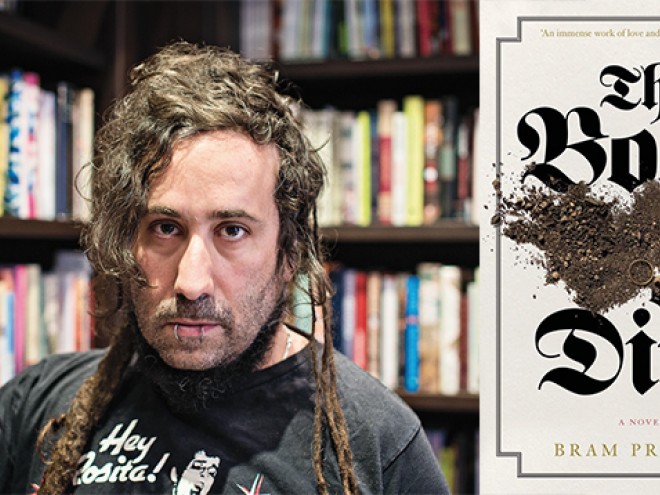

For ten years, Bram Presser schlepped around the world as the singer of iconic Jewish punk band Yidcore before turning to writing. His debut novel, The Book of Dirt, was released in Australia to great acclaim and won numerous major literary prizes. It was recently published in the USA where it won the National Jewish Book Award for Debut Fiction.