One important category of Holocaust-themed literature is the story of Jewish resistance. Joshua Greene’s account of Celia Cimmer’s escape from the Nazis and subsequent role in a band of partisans offers one such version of Jewish defiance. Using a hybrid format of factual material, invented dialogue, and interior monologue, Greene crafts a compelling narrative while conveying important information. He explains in his author’s note that the book is based on interviews and other testimony, and that he did alter some minor or ambiguous details. Separate chapters, alternating with Celia’s story, present historical materials, and correct misconceptions about the era. The book is a carefully balanced work, structured to engage the reader’s attention and confront difficult truths.

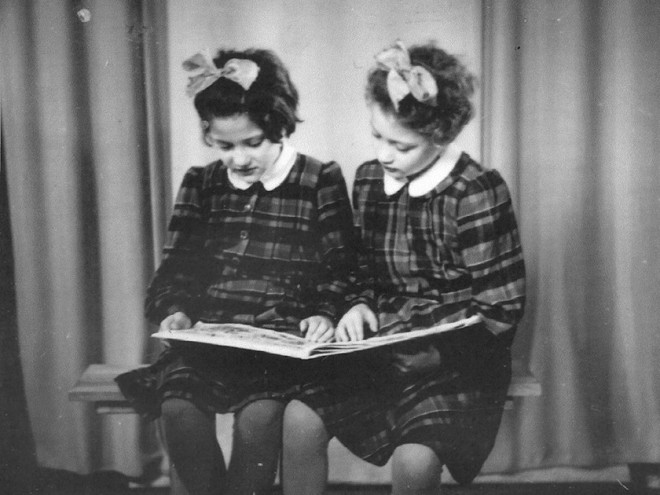

Nothing in Celia Cimmer’s young life indicated how she would respond when the Nazis invaded Poland. Throughout the book, Greene repeatedly denies facile explanations of heroism, unbridled hope, or fate as explanations for her survival. Like many Jews in Europe, she Celia is stunned to learn how quickly her non-Jewish neighbors turn against the Jews who have shared their land for centuries. When the Nazis force Polish Jews into ghettoes, their previous lives seem unrecognizably distant, as they are subjected to starvation, disease, and violence. Celia has several siblings; her younger sister, Slava, plays a key role in the book. Celia never idealizes her mother’s dedication, constrained by the impossible conditions imposed on her, but the desperate choices she made are embedded in Celia’s consciousness.

The informational chapters begin with the assumption that readers may lack a base of knowledge about the Holocaust. Greene briefly explains the causes of European antisemitism, the crucial, if limited, role played by Jewish partisans, and the distinctions among different kinds of internment and labor camps, as well as killing centers. A chapter on resistance points out that, in addition to armed struggle, Jews used other methods to fight back. These chapters do not function as digressions; they are placed strategically to offer ongoing context as Celia’s story unfolds.

Celia’s consuming task of survival leaves her “numb.” She feels betrayed by her Jewish education; it seemed that “God had disappointed her.” After the war and her emigration to the United States, her psychological state of dislocation lingers, affecting her relationships and her sense of purpose. Although Celia’s experience as a fighter against Nazi terror demonstrates tremendous strength, it is clear that the wounds she suffers are far from transient. In this context, Greene’s commitment to bear witness to Celia, and to Shoah’s other victims and survivors, takes on a deeper urgency.

Emily Schneider writes about literature, feminism, and culture for Tablet, The Forward, The Horn Book, and other publications, and writes about children’s books on her blog. She has a Ph.D. in Romance Languages and Literatures.