The February Revolution of 1917 ushered in the emancipation of three million Jews in what had been Tsarist Russia. Under the Provisional Government, Jews were granted full political and civil rights, and the restrictions confining most Jews to the Pale of Settlement were lifted. For many Jews, this sudden emancipation — a possibility unimaginable to the generations that came before — took on a profound significance. In this first volume of a six-part series about Jewish life in the Soviet Union, Elissa Bemporad notes that in the former Russian capital of Petrograd (now Saint Petersburg), many families read the March 22nd emancipation decree at their Passover Seder in place of the Haggadah.

Russia’s Provisional Government lasted until the October 1917 Bolshevik coup. A power vacuum unleashed a civil war and hundreds of pogroms in Ukraine and Belarus. The scale and brutality had no precedent. Many Jews decided to support the Bolsheviks. This choice was a pragmatic one; as the war dragged on, Red Army troops became far less likely to commit acts of anti-Jewish violence. The Red Army’s victory and the establishment of the world’s first socialist state marked the beginning of a turbulent transition: from Russian Jews to the “New Soviet Jewish Man and Woman.”

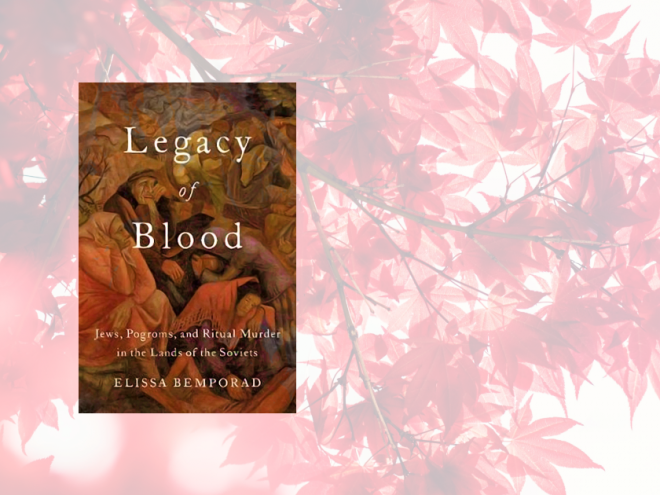

Few people are better equipped to write the story of the first decade of Soviet Jewish history than Bemporad, the author of two previous books about Jewish life in the nascent Soviet state and a leading scholar of the civil war pogroms that raged after the Russian Revolution. Her strength lies in pairing a wide historical sweep with vignettes drawn from the experiences of the Soviet Union’s new citizens. The result is a work that confronts the ambiguities that emerged in Soviet Jewish identity.

Contrary to the popular belief that Soviet Jews were completely severed from their religious and cultural practices, many families in the western borderlands preserved traditions — even amid ongoing antireligious campaigns. Somewhat paradoxically, they had help from the state. In its drive to indoctrinate the masses in Marxist ideology, the Soviet Union funded Yiddish-language schools, reasoning that children would learn better if they heard lessons in their first language. Among the ideologically-inclined young people who forged new lives in Russia’s growing cities — and who reached previously-unimaginable professional success — certain practices endured. Birth and death rituals, the preparation and consumption of Jewish foods, and circumcision, among other traditions, remained markers of Jewish identity.

In the 1920s and 1930s, freed from official restrictions, many Soviet Jews experienced rapid upward mobility across all aspects of their lives. Bemporad argues that in Europe, only German Jewry in the Weimar Republic fared better. For the Jews of Crimea, the Caucasus, Georgia, and Central Asia, the Sovietization project took hold much more slowly.

Taken together, these divergences and cultural negotiations produce a portrait of Soviet Jewry that is neither one of simple rupture and assimilation nor seamless continuity. Bemporad reveals a world suspended between violence, opportunity, and tradition — and a people remade not in a single revolutionary moment, but through a decade of uncertainty, adaptation, and survival.

Maksim Goldenshteyn is Seattle-based writer and the author of the 2022 book So They Remember, a family memoir and history of the Holocaust in Soviet Ukraine.