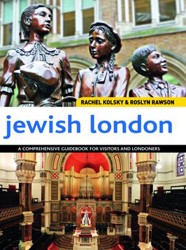

In 1955, Professor Dov Noy resisted the push for a homogeneous new Israeli society that would downplay the traditions of immigrants from the Diaspora. With a team of his folklore students, he began collecting and preserving stories from newcomers and longtime resident Israelis under the aegis of the Museum of Ethnology and Folklore. Today, the Israel Folklore Archives, holding 24,000 tales in Hebrew, continues its work as part of the University of Haifa. Haya Bar-Itzhak, the longtime director, along with coordinator and researcher Idit Pintel-Ginsberg, celebrated the fiftieth anniversary of the many narrative voices in the archive with the publication of The Power of a Tale in Hebrew in 2008. Now in 2020, shepherded by Professor Dan Ben-Amos, comes the English translation of that jubilee collection.

With voices of fifty-one narrators from twenty-five ethnic groups, forty-one transcribers, and thirty-eight scholars from Israel and the United States, The Power of a Tale toasts the founder of the IFA and honors his memory. The book does not have one particular audience in mind, and not every entry or conversation may offer individual insight or allure, but there is something here for everyone—folklorists, anthropologists, storytellers, academics, psychologists, historians, rabbis, literary and cultural appreciators.

The fifty-three very different stories here represent traditions of Ashkenazi, Sephardic, and Israeli Jews, along with Druze, Bedouins, Christian Arabs, and Muslims. The greatest number of ethnic narratives come from Poland and Morocco. Story genres and themes include legends about place, history, sacred people, and miraculous salvation of Jewish community, plus myths, wonder tales, demon tales, realistic narratives, and moral and cautionary tales.

Reflecting the breadth of the collection, the opening tale from Lithuania about a young woman who escapes marriage to a demon is followed by a set of three short legends from Iraqi, Polish, and Israeli Sephardi cultures about sacred stones in and from the Western Wall. In a surprising Druze tale, the gift fish delivered by a fisherman’s daughter spits tar at the queen; the sheikh advises her to tell the king that if the fish is forced to say why, the queen will be sorry. In other contributions, readers will discover contrasting views on how the village of Tarshiha was named, how the flying camel became a symbol for the international Levant trade fair of the 1920s and ’30s, and a sympathetic story of the baby who became the legendary Carpathian Mountain robber Dobush.

Narratives arrive from many voices and range from four-sentence, outline-like prose to professionally shaped, ready-to-share tales. Some of them may be known to readers: the Ethiopian woman who seeks the hair from a lion’s mustache in order to improve her relationship with her husband; a broken oath made by a woman rescued from a well and witnessed by a weasel; and the triumph of a riddle-solving daughter over the stubborn arrogance of her husband, the king. But most will be new to English readers. Others, like the Moroccan version of Rapunzel, demonstrate how stories jump across cultures.

Myriad approaches to commentary abound in the essays. These include Esther Scheely-Newman’s feminist analysis of the positive female protagonist in “Mother’s Gift Is Better Than Father’s Gift” and Peninnah Schram’s discussion of the place of riddles in Jewish oral tradition in “The King and the Old Woodcutter.” Other scholars have analyzed the tales they chose by their deep structure and psychic implications. Many explain customs, geographical locales, and story sources. Some read more smoothly in English than others. Extensive bibliographies and notes support their interpretations.

In the simple story of a Polish immigrant’s encounter with a snake across the threshold of his rural settlement house, the recent director finds a universal truth about how resourceful newcomers make use of whatever is at hand to come to terms with their new worlds by turning “chaos into cosmos.” In the simple story of a Polish immigrant’s encounter with a snake across the threshold of his rural settlement house, the recent director finds universal truth about how resourceful newcomers make use of whatever is at hand to come to terms with their new worlds by turning “chaos into cosmos.” So it is with The Power of a Tale itself. The multitude of voices here tell, present, and analyze fifty years of stories from various perspectives. From “chaos into cosmos”— the collection challenges and excites, bringing the reader to a new home.

Sharon Elswit, author of The Jewish Story Finder and a school librarian for forty years in NYC, now resides in San Francisco, where she shares tales aloud in a local JCC preschool and volunteers with 826 Valencia to help students write their own stories and poems.