In Always Carry Salt, Samantha Ellis crafts an urgent and tender exploration of cultural extinction, maternal inheritance, and the impossible task of preserving what history threatens to erase. Ellis is the daughter of Jewish refugees who fled Iraq — her father in 1951, a decade after the Farhud, and her mother in 1971. Ellis grew up in London surrounded by the distinct sounds of Judeo-Iraqi Arabic, a language now teetering on the edge of oblivion. When she realizes she cannot pass these linguistic treasures to her son — that he won’t understand if she tells him he’s “living in the days of the aubergines” or warn him to “always carry salt” — the floodgates open to a profound meditation on loss, resilience, and intergenerational trauma.

The book’s title, a Judeo-Iraqi phrase meaning “to be prepared” and “to carry protection,” becomes a metaphor for the entire project of cultural preservation. Ellis asks not just what we carry forward, but how we carry it, and at what cost. This and other colorful idioms, like “chopping onions on my heart” (rubbing salt in the wound), reveal a linguistic richness that defies easy translation, each phrase encoding entire worldviews and emotional registers that disappear when the language dies.

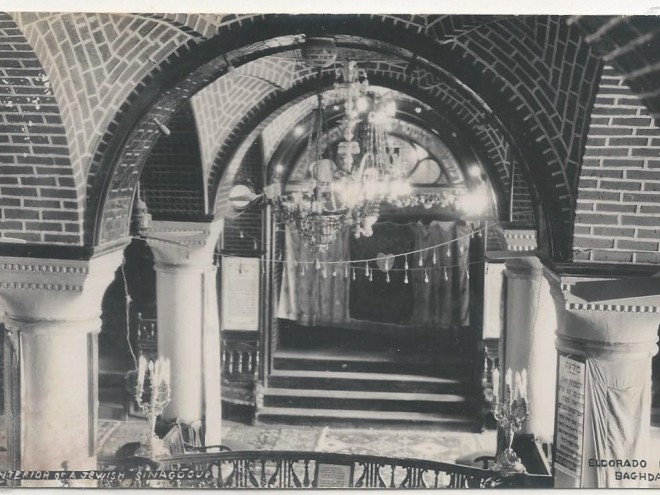

Ellis’s journey is both scholarly and deeply personal. As she says early in the book: “It feels important to tell our story because it is not over. Its consequences are still reverberating — and not just for us.” She travels from the British Museum’s collections to the Oxford School of Rare Jewish Languages, goes from examining ancient demon bowls to standing on the banks of the River Tigris. Throughout, she grapples with questions that resonate far beyond her specific diaspora experience: How do we transmit heritage without transmitting trauma? What must we release to preserve what matters most? Will her son ever love mango pickle as much as she does? These seemingly small questions — about food preferences, about whether certain words will survive — carry enormous emotional and existential weight.

The memoir’s strength lies in Ellis’s refusal to romanticize or simplify. She writes with clear-eyed honesty about childhood shame — trading pita and black eggs for cream cheese on white bread to fit in — and the complicated pride that comes with reclaiming what you once rejected. Her prose balances humor and heartbreak, moving fluidly between intimate family stories and broader historical context without becoming didactic. Discussions of kohl’s dangers and celebrations of fusion food serve as windows into a culture’s adaptability and persistence.

What makes this work particularly resonant is its universality. While Ellis traces the specific contours of Iraqi Jewish displacement, she illuminates an essential aspect of the immigrant experience in the contemporary world. The aching sense of cultural loss, the weight of being a bridge generation, the anxiety about what gets carried forward and what gets left behind — these are concerns that transcend any single community. Her exploration of Jewish generational trauma beyond the Holocaust narrative expands our understanding of diaspora and displacement.

Ellis, an accomplished playwright and author of How to Be a Heroine, brings a theatrical sensibility to her memoir, creating scenes that are immediate and immersive. The book stands alongside works by Marina Benjamin and Claudia Roden in documenting the Mizrahi Jewish experience, but with a distinctive focus on linguistic preservation that feels especially urgent in our present moment.

Always Carry Salt is more than a memoir — it’s an act of cultural rescue, a love letter to a disappearing world, and a meditation on what it means to carry ancestral memory forward into uncertain futures.

Shamar Hill, an Ashkenazi and Black writer, is the recipient of numerous awards, including a New York Foundation for the Arts Fellowship, a Cave Canem fellowship, and a fellowship from Fine Arts Work Center. He is working on a memoir and poetry collection.