Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

The author’s grandparents, Nana Aziza and Abba Naji

Photograph courtesy of the author

My Iraqi grandmother’s hands shone with olive oil and faded burn marks. They were always moving — kneading, crushing, chopping, sautéing, pouring, and spooning — the turquoise-studded gold bangles around her wrist a glorious jangle. When I was a little girl in Sydney, she would sometimes massage my back. I could not speak Judeo-Arabic or Hebrew, and her English was a pidgin mix. Our language was that of our hands.

I wrote Shoham’s Bangle because I wanted to tell the story of my grandmother’s bangle, which I now wear around my own wrist. It wasn’t until later that I realized that the book also spoke to a larger shift in Iraqi Jewish women’s history.

Every family deals with the past differently. My family chose silence. Although I was fed Iraqi Jewish food, sung Iraqi songs, and heard Judeo Arabic, I was not told about Iraq or the rich Babylonian Jewish community that had lived there for 2,600 years. I was not told about Operation Ezra and Nehemiah, the airlift of over 120,000 Iraqi Jews to Israel. I was not told why they had to leave. I was told, “Be quiet and study hard.”

So instead of asking questions about my roots, I absorbed Iraq through my grandmother’s open home, teapots of cardamom tea, cheese-filled sambusek, ba’aba tamar date cookies, and the delicate, simmering spices of cumin, baharat, and turmeric. Perhaps I always felt there was something more to these spices. Inside every kubbeh ball was a hidden tale.

I knew from a very early age that I wanted to be a writer. I read words wherever they appeared — milk cartons, cereal boxes, street signs. Books like Enid Blyton’s The Faraway Tree and Sydney Taylor’s All-of-a-Kind Family series offered magical other worlds and immigrant tales. It never occurred to me as I buried myself in books that my grandmother and other family members also had a story.

The author’s grandparents with their five children in Baghdad, 1951, before their flight on Operation Ezra and Nehemiah

Photograph courtesy of the author

I got married young (like a good Iraqi Jewish girl), left Sydney, and moved to Johannesburg. I had four boys. I called my grandmother and scribbled down her recipes. After she died I lost something very dear, which I only rediscovered when I moved to Israel seven years ago. I began to research the story of the Iraqi Jews, especially the women, whose lives changed dramatically with the plane ride from Iraq to Israel.

Shoham, the protagonist of my book, would have gone to school in Baghdad. I like to imagine that she went to the Laura Kadoorie School for girls, which by 1950 had over 1300 students. While she studied, her bangle would have jingled, a reminder of generations of Jewish women stretching from Babylonian times through the Ottoman Empire. There were no banks in Ottoman times, and so jewelry was the depository of family wealth worn by women, who were safely guarded at home. Home was still a girl’s destiny in 1950’s Iraq. Shoham was to be an Iraqi Jewish wife and mother, the heart of the family.

In Israel, however, these strictly defined traditional roles were broken. Refugee poverty meant that Shoham’s mother, like many Iraqi Jewish women, had to work in factories, in low-wage jobs. In Iraq, this would have been a dishonor and embarrassment. In Israel, it was survival.

This shift in expectations meant that girls could have a different destiny from their mothers. They had the opportunity to leave their homes earlier, to envision meaningful work and professions. A life beyond the stove. Yet, I imagine that even as Shoham entered the freedoms of an Israel where girls wore shorts, and mixed freely with boys, her bangle would clink on her wrist, as it does on mine.

She would remember that her bangle was smuggled from Iraq by her clever Nana. She would remember that her bangle is the symbol of many wise, female hands, who guarded family and wealth before her. And I wonder if her bangle jangled her consciousness as it does mine.

The bangles on my wrist remind me of my illiterate grandmother whose wisdom ran deeper than words. My bangles echo in the silence of my kitchen. What have we lost? I wonder. It’s in the empty space next to me at the stove where my grandmother once stood — where I feel not just the loss of the Iraqi, Babylonian Jewish community’s language and history, but also the lost female secrets, the absent mother, the silenced chatter of generations of women cooking together.

For me, this is the tension of Shoham’s plane ride from Iraq to Israel, the cultural clash of East and West. It is the question that jangles on my wrist between the stove and the computer screen. It is why I want to feed my children poetry, why I want to feed them kubbeh bamya stew. It is why I want to continue the Iraqi Jewish legacy of my grandmother who didn’t know how to read or write, but knew the secret of chopping onions joyfully.

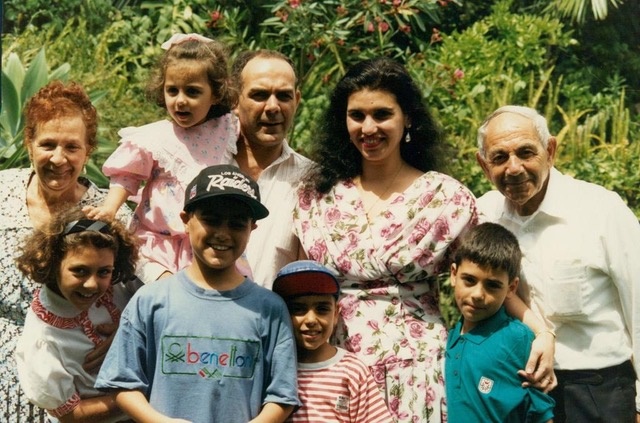

The author’s family, including Nana Aziza and Abba Naji, in Sydney, Australia

Photograph courtesy of the author

Sarah Sassoon was raised in Sydney, Australia, surrounded by her loving Judeo-Arabic speaking Iraqi Jewish immigrant family. When she married, she immigrated to Johannesburg, South Africa and with her husband and four sons, made Aliyah. She lives in Jerusalem. Sarah loves writing poetry and stories about crossing borders and other worlds. Shoham’s Bangle is Sarah’s first children’s book.