Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

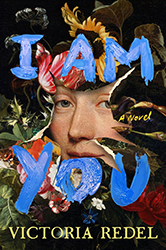

Young Woman Peeling Apples, cropped, Nicolaes Maes (Dutch, Dordrecht 1634 – 1693 Amsterdam), 1655

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Bequest of Benjamin Altman, 1913

The question asked as soon as people hear about I Am You—a novel of secrets, ambition, love, betrayal, and two women painters in the seventeenthth-century Dutch Republic — is, “Didn’t that involve tremendous research?” The obvious answer is, yes, of course, and with pleasure. I describe to them years of studying pigment, paint preparation, and the many books and articles I gobbled up, so that I’d become adequately fluent about daily life, law, food, global trade, and markets during this time.

Still, even after proving my researcher bona fides, I suspect lurking beneath the question is the unspoken one: “Why bother?” There are many ways I could answer. But most simply, it makes writing the novel more unexpected. Most of what I learn, admittedly, I’ll never use, but it’s still essential to fully understand both the physical and cultural landscape so that every detail is vivid and rings true. I hardly knew, for example, when I started writing I Am You, that a Portuguese Jewish family would play an essential role in the novel.

Gerta, the narrator of I Am You, has an identity that is secretive and ever-shifting because of external demands. She finds herself in dire circumstances where she needs to be cared for and harbored. I remembered reading about the Conversos, or hidden Jews, who’d fled Spain and Portugal, finding in Amsterdam a welcoming new home. I knew that there was a vibrant Jewish community in Amsterdam during the Dutch Golden Age. Rembrandt had paintings and etchings depicting both the wealthy and working-class Jews of Amsterdam, and almost a third of his paintings are of Old Testament themes. One of Rembrandt’s homes abutted the Jewish Quarter. Some scholars have even asserted that he converted to Judaism. By the late 1600s, there were Sephardic and Ashkenazi temples in the city, and Jewish merchants had established themselves as central to the thriving Dutch economy. And so it occurred to me, for both historical and metaphoric resonance, who better to take Gerta in, heal her, and provide safety than a family who, for the first time in generations, is living an openly Jewish life?

A crucial lesson I’ve learned over and over is that the connections created inside a book are never what is initially planned. It’s what makes the hours and years of writing so exciting.

During the months Gerta lives with the family, she has the opportunity to both learn their practices and have a sense of the peril they faced as Jews in Portugal. Helping the mother of the house cook for the sabbath, Gerta considers, “We are strange creatures — humans — that a dish of lamb neck, eggs, chickpeas, dates, garlic, cinnamon, mint and turmeric might send a person to her death.” Living under their roof, she undertakes to pray and practice as they do. She says, “I wore the lace veil, fumbled and mispronounced prayers. I, who understood a hidden life, prayed as a Jew with Jews.”

As a first-generation American Jew with one grandfather born in Egypt and the other in Poland, a grandmother from what is now Ukraine, a father born in Belgium, and a mother in Romania, the Jewish Diaspora is not unfamiliar to me. Nor is the fate of Dutch Jews in the Holocaust, where the Jewish population was decimated by 80 percent. I’ve always admired those families who took the risk and hid their Jewish neighbors. I couldn’t help but enjoy the tables turned when in I Am You the Jewish family bravely puts themselves in life-threatening danger by sheltering Gerta.

During my research, I encountered evidence of the remains of a seventeenth-century mikvah in Amsterdam. That led down more than a couple hours of rabbit holes —at worst, an example of my procrastination, at best, another bit of Dutch history I imagined I’d never use. I hardly expected that on one rainy night, Ximenes, the mother, and her three daughters would lead Gerta down the slick, narrow streets to bring her for a ritual purification. Suddenly all my “wasted” research came to life as the rainwater funneled through wood pipes, emptying into a wooden barrel, while the sisters carried buckets of heated water to fill the mikvah’s carved stone bath.

I never set out to include Jews and Jewish life in my novel about two Dutch women painters, and their stormy, complex relationship, and yet, the Jewish characters entered the book as inevitably as it might actually have occurred. Gerta, looking for an additional maid, notices the dark-eyed, quiet Diamanta and poaches her from another household with a large staff. That Diamanta is a Jew is not exactly insignificant to Gerta. She would have been aware of the restrictions on Jews in the city. Gerta hopes that Diamanta’s foreignness will make her less intrusive than gossipy Dutch girls.

A crucial lesson I’ve learned over and over is that the connections created inside a book are never what is initially planned. It’s what makes the hours and years of writing so exciting. My job and hope as a novelist is to look not just for my characters’ paths but to welcome the whole world, and in so doing to create a varied and textured encounter.

I Am You by Victoria Redel

Victoria Redel has written four books of poetry and six books of fiction. Her short stories, poetry, and essays have appeared in Granta, The New York Times, Los Angeles Times, and BOMB, and she’s received fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation, the National Endowment for the Arts, and the Fine Arts Work Center. Victoria is a professor at Sarah Lawrence College and splits her time between New York City and Utah.