Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

They had never heard of the Holocaust.

I was standing in front of four hundred and fifty kids— fourth, fifth, and sixth graders — in Phoenix, Arizona.

And they had never heard of it.

I was in Chandler, a wealthy neighborhood of Phoenix. I’d spent the morning watching the sunrise from Hole in the Rock, the most famous red rock formation in town. I’d seen two teenagers — who maybe had been up all night — stumble up the scree slope to get a perch looking eastward. They climbed with arms wrapped around each others’ waists, laughing sweetly. The girl wore Doc Martens and baggy jeans and her hair had streaks of magenta. The boy had tight cropped hair, skinny jeans, and a semiautomatic pistol holstered at his side.

After my morning visit, I ate lunch at a private golf club near the school, as it seemed the most likely place to find a salad. Most of the cars in the lot were white, many were BMWs. From my table in the shade I watched retired men practice their putting and then sit around tables with beer and gourmet burgers. I imagined that they were amicably debating the new tariffs levied against Mexico and Canada, but I was too far away to hear for sure.

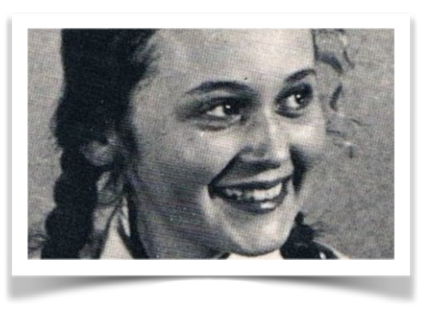

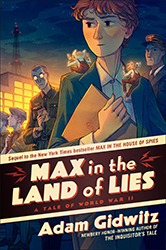

I was nervous about the talk I was planning to give that afternoon. I would be presenting my new book, Max in the Land of Lies, a story about a Jewish boy who escapes Nazi Germany only to return as a spy. His private mission is to try to find his parents, but his official assignment is to infiltrate the Funkhaus, the center of Nazi propaganda. In addition to trying to write a gripping spy thriller (I hope!), the book asks the question: “How did a whole nation of modern, educated people become Nazis?” And my talk in particular would focus on one girl, Melita Maschmann, a middle class German girl not much older than my audience, who had devoted her life to Nazism and had spent the war with a whip in one hand and a German shepherd on a chain in the other, getting Poles and Jews out of their homes and onto trains. I would show them this picture of her:

All photos courtesy of the author

I would tell her life story. And then I would ask them to reflect on how a girl their age, like them in so many ways, could have played such an active role in ethnic cleansing and mass murder.

I was particularly nervous because I had been giving this talk typically to middle schoolers. I wasn’t sure how aware of the historical background the fourth and fifth graders would be.

It turned out that I was right to be nervous. The school was public and the physical amenities did not match the serene wealth of the surrounding neighborhood. But the librarian was lovely — as just about every librarian is — and as the kids filed in and I introduced myself to them, I was struck yet again by how consistent young people’s behavior is, whether they live in Brooklyn or Phoenix or Bangalore. Kids is kids is kids.

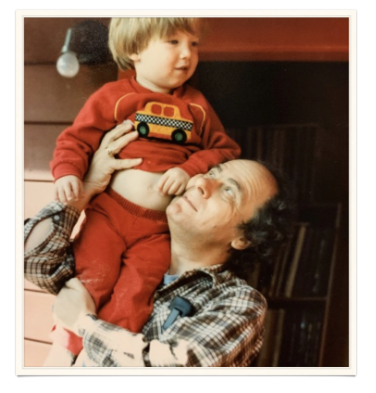

I started by talking about my other books. And then I showed them this photo:

That’s me, with the cute belly, and Michael Steinberg, a close friend of my family’s. Then I showed them this photo:

It’s a picture of Michael Steinberg when he was ten years old, in Berlin, 1938. His mother had just put him on a train that would take him to a ferry that would take him to England, a country he’d never been to, where he barely spoke the language, and he’d live for eight years without knowing if he’d ever see his mother again. And then I asked the students if they had a guess about why his mother would put him on this train that would take him to England.

Right away, someone suggested World War II. I said that was close, but the war hadn’t started quite yet. There were other guesses. (Innocent little girl: “He was poor?” One wise guy: “His mother didn’t like him very much?”). Finally, someone mentioned the Nazis.

“Right,” I said. And then, as I always do, I gave them some background, so we were all on the same page. I mentioned Hitler. Nods all around the room. They’d heard of him. I mentioned the Nazis. Fewer nods, but still plenty. I told them some of what the Nazis believed: that they hated Jews, immigrants, non-white, LGBTQ+, and disabled people. Pretty much anyone who wasn’t a Nazi. The nods faded. The kids’ faces began to look uncomfortable and upset. Some, I imagined as I watched the transformation, because they identified with the groups I was naming. Others, perhaps, because they recognized the rhetoric from home, the neighborhood, or the news. I am not sure of this. But anti-immigrant speech in particular had been pretty heated in Chandler, Arizona. And everywhere else in the United States.

Next, I told them that between 1939 and 1945, people from all these groups, and particularly Jewish people, would be rounded up and put in concentration camps — which were like giant prisons, I said — and then many of these people were killed. There was an audible gasp. Dozens of mouths fell open, or were covered with a hand. (My mother once complained about my writing that I sometimes have someone’s mouth “fall open”; “Does that even happen in real life?” she demanded. It very literally did in Chandler.) I said, “Millions and millions of people were killed.” The mouths stayed open, their faces stricken.

If it had been just the fourth graders who acted so shocked, maybe I would understand. But fifth graders and sixth graders, too, stared at me like I had shown them a terrible truth that they could never unsee. I hadn’t shown them photos of Auschwitz, or even piles of shoes. I’d just said that hatred had turned to murder.

How did we get to a point where a majority of kids in a school in Arizona have heard of the Nazis — and yet were completely blindsided by the fact of the Holocaust? Have we turned the Nazis into such cartoon villains, such tropes of Hollywood storytelling, that the nature of their villainy has been erased from the public memory?

And what can we do to remind the young people of our nation — strike that, the people of our nation — strike that, the people of our world—that rhetoric leads to hatred, and hatred leads to murder?

One thing we must do is stop hiding uncomfortable truths from our young people. When we ban a book because it might make a child uncomfortable, we are excising from our collective memory a wrong that, forgotten, we are liable to repeat. We Jews like to say, “never again,” but if students in Department of Defense schools can no longer read 1984 or Fahrenheit 451, if the students of Chandler don’t know why it’s terrifying when a presidential candidate says “one more child to sacrifice on the altar of open borders” (for the record, because accusations of children sacrificed to immigrants is inspired by the Blood Libel), if we prevent protesters who make us feel like the bad guys from pointing out that, from time to time, we may in fact be the bad guys… then “never again” becomes an empty phrase. And the Holocaust and its hallmarks — demonization, mass roundups, incarceration without trial, violence against a scapegoated minority — will happen again. If kids don’t learn what happened, in honest, uncomfortable detail, it will not only happen again — it’ll be much closer to home this time.

Max in the Land of Lies: A Tale of World War II by Adam Gidwitz

Bestselling author Adam Gidwitz was a teacher for eight years. He told countless stories to his students, who then demanded he write his first book, A Tale Dark & Grimm. Adam has since written two companion novels, In a Glass Grimmly and The Grimm Conclusion. He is also the author of The Inquisitor’s Tale, which won the Newbery Honor, and The Unicorn Rescue Society series. Adam still tells creepy, funny fairy tales live to kids on his podcast Grimm, Grimmer, Grimmest—and at schools around the world. He lives in Brooklyn with his wife, daughter, and dog, Lucy Goosey.