For Jewish Book Month, Jewish Book Council has teamed up with Yeshiva University to highlight new books in the broad field of Jewish scholarship. For many of us, scholarly books, particularly those on ancient times, belong only to the world of academia. But often, the history and thought in these books have direct relation to contemporary ideas, events, and rituals.

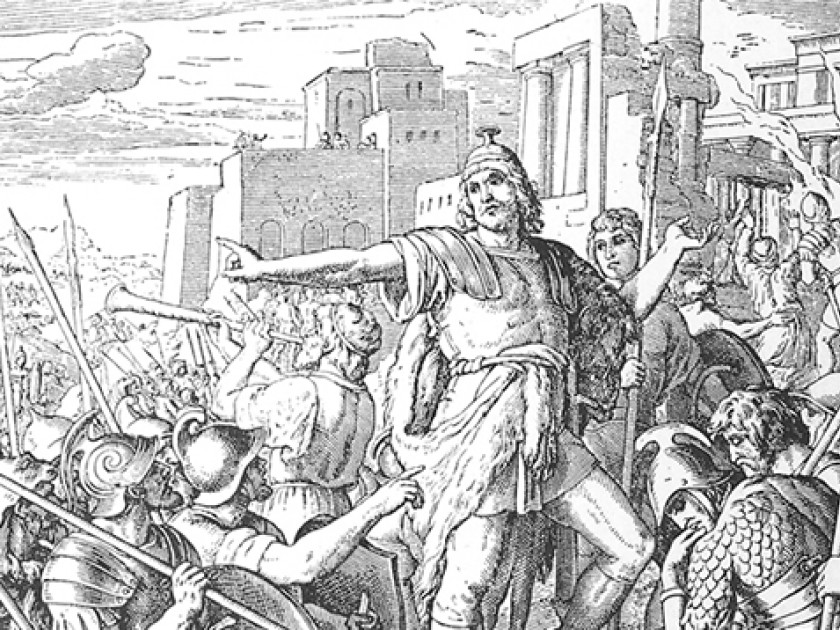

Every Jewish schoolchild knows of Judah Maccabee; perhaps they’ve even dressed up like him for a Hanukkah play. Similarly, every historian of the period places this fearsome military leader at center stage, regardless of whether they describe him as a heroic freedom fighter or as a fundamentalist religious terrorist. Remarkably, however, Judah’s name appears nowhere in all of rabbinic literature. This absence requires explanation, especially when contrasted with the heroic description of Judah in the Books of Maccabees, and his even greater aggrandizement in the four hundred paragraphs about his achievements in the writings of Josephus.

Nineteenth-century scholarship portrayed the Pharisees and rabbis as caring only about religious freedom rather than political sovereignty. The rabbis accordingly downplayed military activism, which might encourage a dangerous replay of anti-Roman revolts, in favor of religious and spiritual leadership. These scholars pointed to the lack of a Mishnaic tractate for Hanukkah, statements opposing non-Davidic kings, and the de-emphasis on the military victory in favor of the miracle of the cruse of oil as the basis for the holiday.

After the 1930s, however, historians questioned the earlier interpretation and instead emphasized pro-Hasmonean statements in rabbinic literature and assumed literary rather than political explanations for the centrality of the cruse of oil story. In part motivated by Zionist ideology, this scholarship paved the way for a positive view of the Hasmoneans as models for modern Israeli statehood. These scholars correctly noted that rabbinic literature is not historiography, and therefore omission of even significant events need not arouse attention. Nevertheless, Judah the Maccabee seems too central to miss even taking into account the spotty nature of the Talmud.

Vered Noam, in her book Shifting Images of the Hasmoneans: Second Temple Legends and Their Reception in Josephus and Rabinnic Literature, resolves this aporia and arrives at a more nuanced conclusion by separating individual Hasmonean leaders from their collective achievements: “The rabbis cherished the Hasmonean victory and the national freedom to which it gave birth, but steadfastly refused to regard military-political leaders as figures worthy of emulation. Instead of idolizing a fighter, the leader of a rebellion, they preferred to ignore him as an individual and to praise an anonymous victory.”

While the Talmud censors the names of the first generation of Mattathias’s sons, they do mention positively the second generation Hasmonean leader John Hyrcanus. But that is only because they are able to portray him as a rabbinized sage who received prophecy, drawing on an ancient tradition also cited by Josephus. For the next two generations, Talmudic stories vilify Alexander Yannai and his sons and defend the reputation of the Pharisaic leaders. In sum, the rabbis endorse the political aspirations of the Hasmoneans, but praise individuals Hasmoneans only if they fit into a Pharisaic/rabbinic model.

All of this contrasts with Josephus, who extols the Hasmonean leaders beyond even the praise lavished on them in 1 Maccabees, his primary source. He also introduces some criticisms of the Pharisees in order to mitigate the evil of the last generations of Hasmoneans. Josephus may have ended his days in the Pharisaic camp, but he also remembered his Hasmonean ancestry and, in a conflict, preferred the latter over the former.

With her typical erudition and insight, Noam reviews six significant narratives about the Hasmonean dynasty as recorded in Josephus and rabbinic literature. This book focuses less on what really happened and more on what Josephus and the rabbis thought of the Hasmoneans. She does this by peeling away each layer of these traditions so that they can be compared and contrasted side by side.

While previous scholars have assumed that the rabbis drew their stories directly or indirectly from Josephus, Noam’s project proves that rabbinic traditions stand independent of Josephus and that both draw upon earlier sets of traditions, many deriving from now-lost Pharisaic sources. Fascinatingly, this means that some details within rabbinic stories may retain greater historical accuracy than discrepancies in Josephus, despite the former composing their works centuries after the latter.

Having become one of the most popular holidays in the Jewish calendar, Jews today continue to celebrate Hanukkah and retell the stories of Judah the Maccabee and his family. Different people will choose to emphasize various aspects of these stories to reflect their own views on politics, power, sovereignty, and assimilation. But this is nothing new. As Noam demonstrates, each narrative retelling teaches us as much about their original Maccabean subjects as about the storytellers themselves.

Image via Die Bibel in Bildern / Wikimedia Commons

Rabbi Dr. Richard Hidary is Associate Professor of Judaic studies at Yeshiva University and author of, most recently, Rabbis and Classical Rhetoric: Sophistic Education and Oratory in the Talmud and Midrash (Cambridge University Press, 2017)