“Falls in Love, or Reads Spinoza,” a poem from my 2017 collection Line Study of a Motel Clerk, is in conversation with H. Leivick’s cycle on Spinoza and Charles Reznikoff’s “Spinoza” (1934). It is also in the tradition of rebelling against T.S. Eliot, joining Emanuel Litvinoff’s “To T.S. Eliot” (1951), Hyam Plutzik’s “For T.S.E. Only” (1955), and Philip Levine’s decision to skip meeting Eliot at a bookstore in 1953 after spending “a sleepless night wondering what I might do if Eliot were suddenly to blurt out a racist remark.” I anticipate anti-Semitism when reading Modernists, so I was prepared for Eliot’s overtly problematic poems, but nothing prepared me for this line in “The Metaphysical Poets” (1921): “The latter falls in love, or reads Spinoza, and these experiences have nothing to do with each other…”. That is, unless, Spinoza is part of your worldview. That is, unless, you have a father who reads Spinoza relentlessly, who leaves a copy of Ethics on the back of the toilet so “the latter” might take a shit and read Spinoza, let alone fall in love. But Eliot didn’t grow up in my home. And he certainly didn’t have my father.

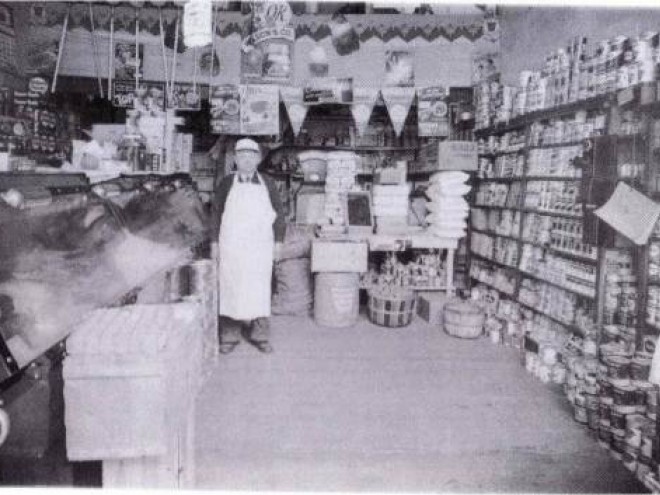

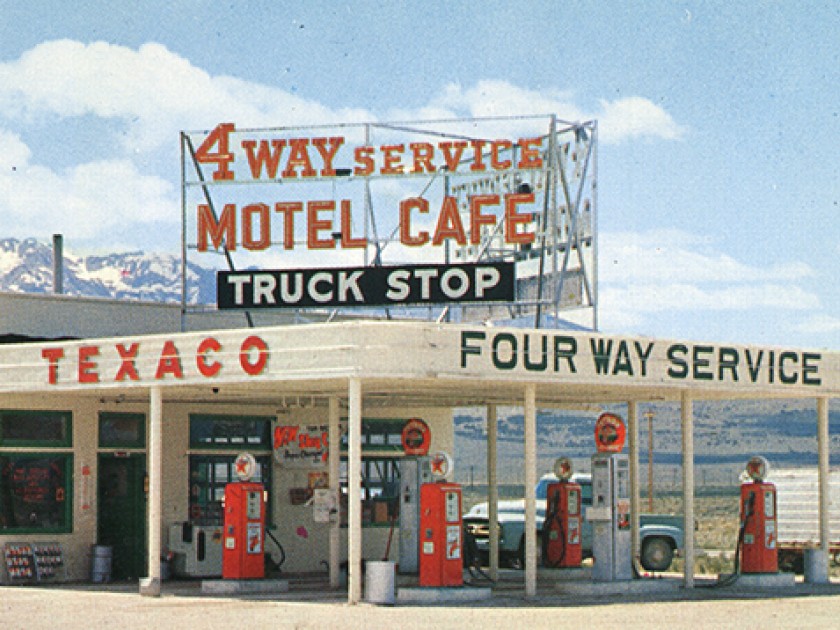

The kind of Judaism that shaped my collection was handed down to me by my father and uncle, who run a trucking motel in the Rust Belt. It was originally opened in 1960 by my grandfather, the eponymous “motel clerk” of my collection. To the casual onlooker, the motel isn’t Jewishly marked. The mezuzah is painted over (by accident? for safety?) and we only sell Manischewitz through the beer-and-wine drive-thru before Passover. My father’s perpetual head covering is a baseball hat, not a kippah. But the motel is where, behind spare ashtrays and wooden tire thumper, my old Jewish Studies books line the bookshelf. Where, between checking in drivers, my father wrote his address for my sister’s bat mitzvah. Where I drove to at dawn the morning of my wedding to pick up my grandma, fresh in from Deerfield Beach, and originally from Montreal, where she was raised down the street from Mordecai Richler.

Beside the motel is a roadside restaurant — the setting for my poem “The Marquee Is Empty at the Big Rig Saloon.” My father and I have been eating at the restaurant since we’ve been babies. Currently, its interior includes deer heads and a steady stream of country music and Fox News. It is perhaps not a likely place to find a man with a name that you don’t hear outside of Canadian Jewish nursing homes and his poet-daughter, but when I’m home, it’s where my father and I go after work for a drink. Whatever we talk about ends up being about the Holocaust because my father, when not reading about Spinoza, reads about the Holocaust. He reads books with titles so grim that he tapes paper over them when reading in public so people don’t give him looks. When we walk into the restaurant, truck drivers around the bar offer to buy him beers. We sit in a booth, drink Coors Lights, and then we stop passing as normal customers because we are drunk and talking too loud about Treblinka.

I wrote that poem and this essay because I suspect that there are readers like me who find nothing strange about love and Spinoza, about Coors Light and Treblinka. If there is a particular strain of Rust Belt Jewish culture, perhaps it’s in “Once” (1999) when a weary Philip Levine shows up at a restaurant in the Lower East Side and the owner exclaims, in disbelief, “They got Jews in Detroit!” It’s Murray Saul, the 1970s-era DJ in my poem “The Motel Clerk’s Son Gets Bad Reception of Cleveland 100.7 FM,” who welcomes in Shabbat stoned and gurgling with his own ferocious spit. It’s mothers writing beautiful, cursive notes excusing their children from school on the High Holidays only to have the attendance workers stare at the graceful lettering in suspicion. It’s parents naming their children “Allison Davis” so we “don’t seem too ethnic.” It’s the economy never recovering from post-industrialism, the persistence of racial and class inequalities. It’s everyone leaving town, and synagogues struggling to make minyans. It’s knowing that Jewish culture will only survive if you shoulder part of the weight, or rather, as you’re born with the extra weight already on you, it’s accepting the gravity, accepting that if you escape it will be at the expense of never feeling grounded again.

I sensed this obligation at a young age, one day in the motel office, when my uncle, after a particularly frantic series of phone calls, told me “Allison, there are two things you should never do: run a trucking motel or be the president of a synagogue.” Yet, all over the Rust Belt, countless people like my uncle are doing what it takes to keep businesses and synagogues open, because the region is our spiritual home, our diaspora once removed from the coasts. It has its own beauty and wilderness, and its authors are navigating it in all of its diversity and complexity. The rest of America can fly over the middle, but not without missing critical literature of our time.

Image via Allen/Flickr

Allison Pitinii Davis is the author of Line Study of a Motel Clerk (Baobab Press, 2017), a finalist for the Berru Poetry Award and the Ohioana Book Award.