As soon as Amos Oz could read, he sat down at his father’s typewriter and wrote the words “Amos Klausner sofer [writer].” He was five years old when he made the declaration that would come to define his life. Robert Alter, a long-time friend of Oz and a professor emeritus of Hebrew and comparative literature at Berkeley, has created a portrait of Oz using the writer’s own words and the words of those close to him.

Much of the background for Oz’s work can be found in A Tale of Love and Darkness, which he wrote when he entered his sixties. Oz describes growing up under the Mandate in a one-bedroom basement apartment in a rundown Jerusalem neighborhood. His parents, immigrants who met at Hebrew University, were unsuited for one another. His father was a pedantic aspiring scholar and a follower of the hard-right Herut party; his mother was a sensitive and romantic woman who told her son imaginative and spooky stories grew increasingly inward and disconnected. When Oz was twelve, she died by suicide, leaving an indelible mark on her only child. Two years after her death, he left the stifling apartment in which he grew up and joined a kibbutz. He broke with his father politically and changed his surname from Klausner to Oz, meaning “strength.” He wrote A Tale after having kept his silence about his mother’s suicide, and his haunting sense of abandonment, for almost fifty years.

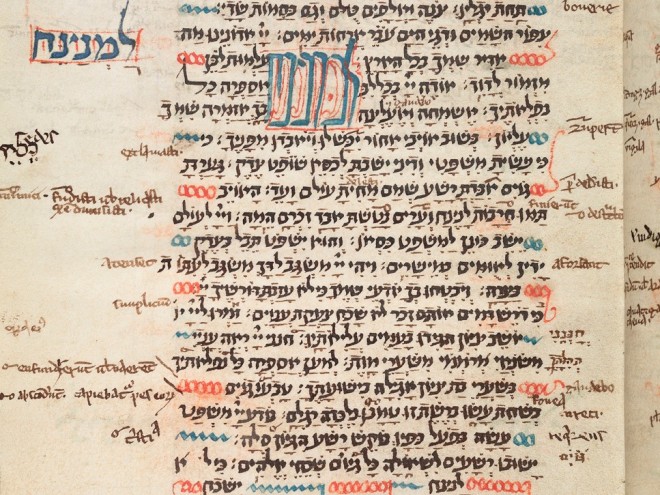

Poetry was Oz’s earliest genre. By age twenty he turned to fiction, but his poetic impulse is apparent all throughout his work. His first book, Where the Jackals Howl, is a collection of short stories set in a kibbutz. Published when he was twenty-six, it marked the arrival of a new voice in Israeli fiction. Unlike the first generation of native Hebrew writers, Oz, while writing in a modern voice, also draws on traditional Hebrew. His language is rich in adjectives, sometimes excessively so; he had the ability to create an extraordinary sense of place. Over the years, Oz responded to critics by toning down his style, but his masterful use of Hebrew remained a hallmark of his work.

From the time he was young, Oz was passionately engaged in Israel’s fraught situation, as were the major Israeli novelists A. B. Yehoshua and David Grossman. He lectured and wrote constantly — sometimes one or two opinion pieces a week. A Zionist but also an optimist and a realist, he believed in the two-state solution and hoped that the coming generation might find the solution to ending a century of bitter hatred. “We are not alone in this land,” he said. His biographer suggests that, in the end, Oz may have seen his legacy not as a novelist but as an advocate for peace and resolution.

Alter brings to this informal biography a portrait rich in candid memories. He deals evenhandedly with Oz’s youngest daughter’s angry and painful break with him, as well as the possibility that his mother’s death might have been an accidental overdose. The book’s strength lies in Alter’s close reading of Oz’s work and in his personal memories of both their friendship and Oz’s public voice. Amos Oz is an intimate and moving analysis of a complicated man, a lifelong activist, and one of Israel’s most prominent and widely read authors.

Maron L. Waxman, retired editorial director, special projects, at the American Museum of Natural History, was also an editorial director at HarperCollins and Book-of-the-Month Club.