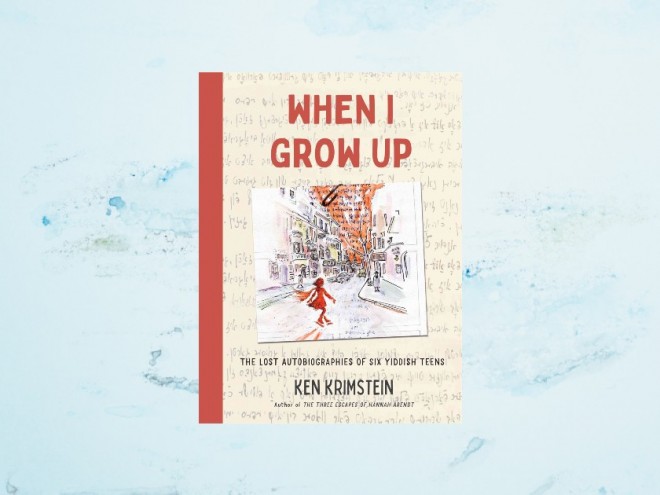

Jewish history is full of unbelievable moments. In 2017, thousands of pages of previously unknown documents were discovered in the basement of a Lithuanian church. Included among them were personal essays submitted to a contest sponsored by the Yiddish scholarly and cultural organization, YIVO. Author and cartoonist Ken Krimstein, with the help of translator Ellen Cassedy, has written and illustrated a graphic nonfiction narrative based on six autobiographical reflections of young Jews written on the verge of the Holocaust. More than an adaptation, Krimstein’s book is a transformation of these works into an utterly original form. Each author speaks from the past with the honesty and introspection of early adulthood, not knowing that the world in which they have grown up is about to be destroyed.

Underlying Krimstein’s project is a commitment to conveying the richness of Eastern Europe’s Yiddish-speaking communities in the early twentieth century. In his “Preface: Crossing the Abyss,” he describes this geographical and cultural entity as “Yiddishuania.” Not a nation, but an intersecting set of choices united by the Yiddish language, this place and time includes religiously observant Jews, secular Zionist, socialists, and many other conflicting Jewish identities. Krimstein’s awareness that this world is now lost, and probably unfamiliar to many readers, forms the framework of the book. His language and images acknowledge that world’s remoteness, but render its voices accessible and relevant today.

Each memoir represents the unique voice of one individual, but also his or her place on the spectrum of experiences in Yiddishuania. “The Eighth Daughter” recounts a nineteen-year-old girl’s role within her large family, her literary aspirations, and her emerging feminism. Forbidden by traditional Judaism to say kaddish, the memorial prayer, for her father, she begins to question the irrational basis for excluding women from ritual. Krimstein demonstrates how the writer’s feminist consciousness is her intrinsic response to orthodoxy, not a twenty-first century idea imported into the past. “The Letter Writer” offers a glimpse into the Yiddish press, as well as the Kafkaesque ordeal of a twenty-year-old Jew fighting American legal restrictions against immigration. The author of “The Boy Who Liked a Girl,” is tormented by the conflict between his romantic feelings and his spiritual aspirations, and by the irreconcilable differences between secular and religious Jews. Krimstein’s footnotes to each document are an ingenious mechanism. He deliberately steps outside the narrative, inviting the reader, through his informative, ironic, and humorous comments, to a dialogue with the past.

Stunningly imaginative images add a new dimension to the stories. A huge hand tries to engulf the letter writer, dwarfed in size, as he struggles against an unjust system. The eighth daughter becomes one candle on a Hanukkah menorah, lighting her father’s cigarette as he occupies the place of the shamash. A lone figures skater, torn between competing Zionist and socialist movements, finds freedom as a shadowy silhouette freely moving among scenes of different possibilities. Readers will leave this book with a sense of gratitude for Krimstein’s innovative vision of a time and place, rescued from oblivion.

Emily Schneider writes about literature, feminism, and culture for Tablet, The Forward, The Horn Book, and other publications, and writes about children’s books on her blog. She has a Ph.D. in Romance Languages and Literatures.