Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

Teddy Bear stuffer, circa 1912

I started the research for my book, Playmakers: The Jewish Entrepreneurs Who Created the Toy Industry in America, thinking I was writing a simple history of my family: my great-great-uncle Morris Michtom fled the Russian Empire, opened a candy store in Brooklyn, and, eventually, invented the Teddy Bear and started the Ideal Toy Company. But as I dug into my family history, I found that the Michtoms’ story wasn’t all that unusual. In fact, pretty much every single toy company at the turn of the twentieth century was started by first-generation Jews in America: Hasbro, Marx, Pressman, Mattel, Arranbee, Madame Alexander, Effenbee, Lionel trains.

Why were so many of the inventors, marketers, toymakers, sellers, artists, writers, and scholars — the cultural and professional arbiters of this new childhood — Jews? And not just “any” Jews, but first-generation Jews? Why in America but not in England or continental Europe? What does being Jewish have to do with any of this?

This is not a Hollywood fairy tale – although it’s probably worth noting that most of those Hollywood films with those happy endings were also produced by first-generation Jews, as Neal Gabler’s book, An Empire of Their Own: How the Jews Invented Hollywood, so ably detailed. Instead, Playmakers chronicles a story of both triumph and ambitions thwarted and unrealized. As much as these men climbed the ladder of success, they were never fully accepted into the elite circles they yearned to enter. As Jews, they were always outsiders, no matter how close they got to the hallowed inside. Thus, theirs is a quintessentially American story, a story of men who devoted themselves earnestly to the American Dream, achieved great success, only to find, as have so many others, that there is a hollowness and a limit to this fiction. What could be more American than that?

My book is not a triumphalist parade of famous and not-so-famous first-generation Jews that somehow attributes their success to some cultural, ethnic, or even biological “gift.” Nor am I claiming that every great creator of this new American childhood was a first-generation Jew. But it is incontestable that many of them were first-generation Jews, and that this number is far out of proportion to the actual percentage of Jews in the population.

To be sure, Benjamin Spock, Walt Disney, Charles Schulz, and Theodore Geisel had as much to do with the creation of American childhood as any other quartet I can think of – and none of them was Jewish. (Disney, in fact, was rumored to be antisemitic, or at the very least, an ally to known antisemites of his day. It is true, though, that a couple of Dartmouth fraternities rejected Geisel because they thought he was Jewish.). They all saw childhood as a world unto itself — enchanted, inhabited by wild creatures, animated by the eternal struggles of good and evil, in which the good guys inevitably triumphed (except, of course, for dear, sweet, pathetic Charlie Brown, the loser as Everyman). They all imagined a reality that might magically transport children to realms of beauty and safety.

However, these first-generation Jews who became titans in toymaking shaped a new understanding and vision of childhood in the US. That vision of childhood was a significant departure from the prevailing ideas of child-rearing at the turn of the last century in the US. Ever since the Puritans, Americans had seen children as inherently willful, perhaps even wicked, and the entire point of child-rearing was, quite simply, to “break their wills.” Physical affection was discouraged; physical violence was necessary. Sometimes a baby “will cry so hard” they may “have a convulsion,” counseled one 1915 best-selling advice book. When you see this, “turn it over and administer a sound spanking and it will instantly catch its breath.”

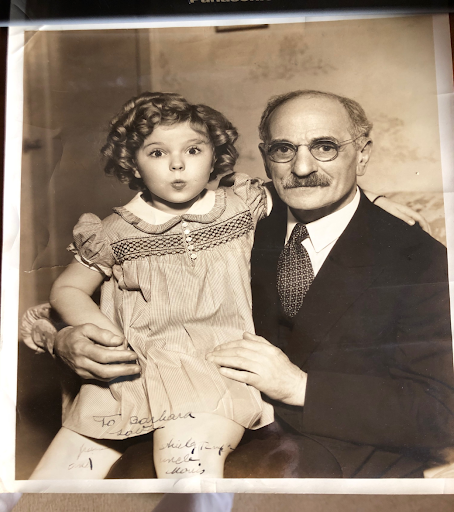

Photo of Morris Michtom and Shirley Temple (photographer unknown) Photo courtesy of Michael Kimmel

While this may not have troubled many of the German Jewish families that had immigrated in the mid-nineteenth century, it did not sit well with that second wave of Eastern European Jews, the Yiddishkeit Jews like Isaac Bashevis Singer, who saw in children’s precocity and wonder the miracle of life itself. Children were a blessing — creative, curious, precious. It was the Yiddish-speaking Jews from the Pale of Settlement, who fled pogroms only to live in squalid tenements on the Lower East Side and other ghettos, who gave contemporary childhood both its form and its content. (Of course, many of these families were fully patriarchal, though so many of these tenement-dwelling men were, themselves, failed patriarchs.)

As I conducted my research and found these commonalities in toymakers, I saw a certain confluence among the various experiences of being a Jew, an immigrant, and being a child. All are outsiders; they look into a world that they cannot enter, but one into which they want desperately to fit. The child looks at the adult world with both wonder and fear, as the American newcomer looks at a world of unparalleled opportunity with anticipation, hope, and fear of discrimination or violence.

Taken together, this group of first-generation Jewish toymakers, artists, writers, child development experts, and others created the idea and material reality of childhood that came to dominate — indeed, that defined—the world of American children for the rest of the twentieth century. Their legacies carry through to today, where seven of the top ten toy companies in the world are either Mattel and Hasbro proper or their wholly owned subsidiaries like Barbie, Fisher-Price, Nerf, and Hot Wheels.

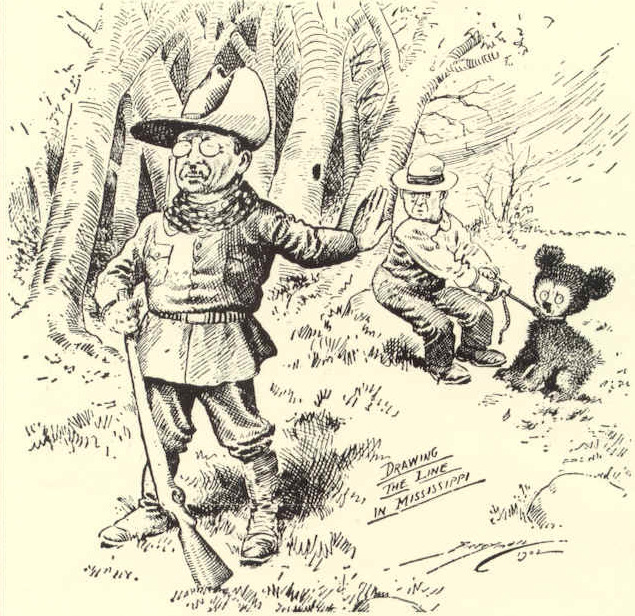

”Drawing the Line in Mississippi” by Clifford Berryman in Washington Post, November 16, 1902. Library of Congress

In my research, I followed these Jewish toymakers first from the shtetl to the Lower East Side, and later to wealthier suburbs. We watch as Morris Michtom creates the Teddy Bear and almost single-handedly starts the modern American toy company. We read how a clever young engineer, Joshua Lionel Cohen, changed his name and invented the world’s most successful electric train set. We listen to African-American celebrities, urged on by Eleanor Roosevelt, as they finally persuaded Ideal’s executives to create the first mass-manufactured Black doll. We sit with a group of wide-eyed young men drawing comics creating the superheroes whose exploits dominated the interest of many youths and whose namesake toys animated so many childhoods. We meet the nefarious “toy king” who simply copied other toymakers’ designs and then undersold them. And we watch an artist couple fleeing the Nazis with a portfolio full of sketches for Curious George. Follow along as three brothers named Hassenfeld took their scrap material business and branched out into, at first, doctor and nurse kits, and eventually, Mr. Potato Head. And marvel when Ruth Handler took a rather risqué German “adult” model doll and created Barbie, the best-selling doll in history — and how every other company kept trying, and failing, to imitate her success.

Some of these stories may already be familiar to you, others less so. But once you hear these pieces of history, I predict you’ll never again be able to look at a comic book, a toy, or a parenting manual again without wondering if it, too, was created by a first-generation Jew. Beyond offering a simple tally of those cultural artifacts and their creators, it’s important to understand the impact of these first-generation Jews who created so many of our childhoods — and, even more importantly, why it matters that they did.

The great-grandnephew of the founder of the Ideal Toy Corporation, Michael Kimmel is a SUNY distinguished professor emeritus of sociology and gender studies and founder of the Center for the Study of Men and Masculinities at Stony Brook University. The author of Guyland, he lives in Brooklyn, New York.