Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

Photo by Carlos Torres on Unsplash

The first magician I ever saw was my grandfather, Saadia Cohen. He never called himself a magician, but he was one — a poet, musician, and dreamer who kept fifty homing pigeons in two large brass cages on his roof terrace in Safi, Morocco, the town where I was born. One day, we painted their wings red, blue, and green, and set them free to burst into the sky. “Fly, little birds, fly!” he said.

Later, I wondered what it was about that moment that moved me so deeply. It was wondrous and beautiful, but also poignant. My grandfather climbing to his roof every day, his refuge — to watch his pigeons fly to places he could not go; the cages were always unlocked, yet the birds always returned. By painting their wings dazzling colors and sending them whirring into the sky like a living rainbow, he gave us all a chance to fly with them. People talked about it for years afterward.

And I never forgot.

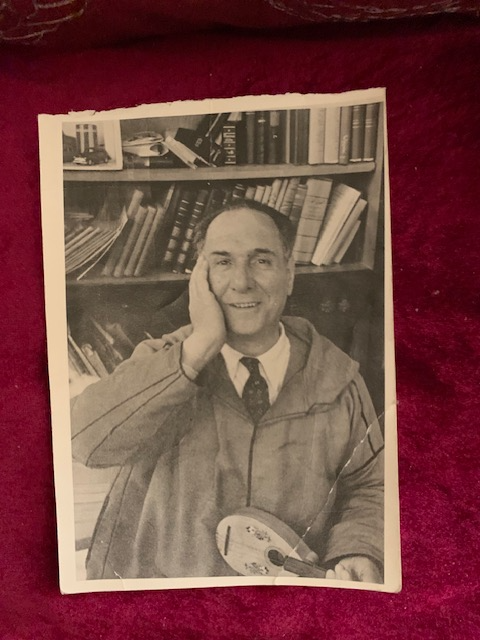

Author’s grandfather.

That day on the rooftop became the seed of a lifelong fascination with transformation for me — the power to turn the ordinary into the extraordinary. Years later, while working on a novel set in Israel during the Yom Kippur War, a character known simply as the Magician kept appearing, though he had nothing to do with the story I was writing. Finally, in frustration, I searched online: “magician – Israel – 1970s.” That was how I found Uri Geller, the controversial psychic-magician known for bending spoons and stopping watches with his mind.

Uri was like a guide beckoning me into the world of magic that would inform my novel, Zigzag Girl. I was fortunate to be welcomed into its secret house and to study with some of the world’s greatest magicians, including Teller and Jeff McBride, and brilliant Jewish magicians like Max Maven, Larry Hass, David Blaine, and Asi Wind.

I read everything I could find — especially about Houdini, born Erik Weisz, the son of a rabbi, whose very name became synonymous with escape. On July 7th, 1912, shackled in handcuffs and leg irons, he was locked inside a packing crate weighted with two hundred pounds of lead and dropped into the East River. In less than a minute, he emerged, free.

There was the Great Nivelli, born Herbert Levin, who performed tricks for children at Auschwitz to help them forget where they were. And David Copperfield, born David Seth Kotkin, whose illusions — making the Statue of Liberty disappear, walking through the Great Wall of China — embody both grandeur and hope. His Project Magic program uses illusion to heal, rooted in the Jewish concept of tikkun plam.

Perhaps it’s no coincidence that so many magicians are Jewish. We come from a tradition of wonder and questioning, of hidden meanings and miraculous escapes — from Egypt, persecution, despair. In our stories, the ordinary world can crack open at any moment to reveal mystery and light.

The author in Marrakesh at the Mamounia. Photo courtesy of the author.

I once went with a magician who volunteered in a children’s cancer ward in Washington, D.C. I’ll never forget the eleven-year-old girl — a pink baseball cap perched on her shaved head, her frail hand touching the Magic Coloring Book. When the black-and-white pages suddenly bloomed with vivid color, her eyes widened, and her mouth fell open in silent awe. In that instant, I understood that magic doesn’t deny reality — it redeems it.

Later, I was sawed in half, sawed in thirds, and locked in a straitjacket — and I learned, not just intellectually but in my bones, that magic is the art of breaking free. When Houdini escaped from jail cells and locked trunks, he showed us that no chains can hold us, no locks can keep us trapped. Magicians are escape artists who remind us that the key to freedom is in our own hands.

All of this research and contemplation led me to write Zigzag Girl, a contemporary mystery set in Atlantic City and the eerie New Jersey Pine Barrens. When magician Lucy Moon finds her friend’s body in a Sawing a Woman in Half Box, she must discover the killer before he strikes again.

I created a small band of fierce, brilliant magicians — Lucy Moon, Stormie Weather, Van Kim, and the mysterious Elvis Jones. For Elvis Jones, a wild magician who works with an unruly seagull, magic isn’t about tricks or deception: “It’s about pushing the limits of who we are and what we can do.”

And then there is Cleo West, a magician who performed on the same Atlantic City stage as Lucy, Stormie, and Van — but seventy-five years earlier during World War II. Every night Cleo was sawed in half before an audience of wounded soldiers, many of them amputees, and every night she rose whole and triumphant. For those men, it was a miracle. A promise that being broken doesn’t mean being destroyed.

The late, great magician Eugene Burger wrote: “Conjuring, at its best, functions symbolically to awaken us to another realm of experience: the magical dimension that points toward the Mystery that lies behind and beyond all experience.” His legendary performance of the centuries-old Gypsy Thread is a masterpiece of simplicity — a strand of thread broken into pieces, then restored in the magician’s hands. To me, this deceptively simple illusion captures the promise of magic.

It may seem ironic that magic — an art once condemned for daring to imitate the gods — turns out to be the most human of arts. It captures our need to believe, even for a moment, that we can transform ourselves, conquer death, and free ourselves from any prison. In the hands of a master, the magic spills from the stage and illuminates the audience, inviting us to share in wonder, possibility, and hope.

A single strand of thread, torn and restored.

A man bursting up from a river, freed from death.

Children watching magic in a place of horror.

Painted birds flying from a rooftop.

And a writer feeling her grandfather’s hand on her shoulder as she sets her book free — to fly with the birds.

Born in Morocco, Ruth Knafo Setton is the author of the novels, The Road to Fez, and Zigzag Girl—which won Grand Prize in the ScreenCraft Cinematic Book Competition and First Prize in the Daphne du Maurier Awards. Her TV pilot based on Zigzag Girl won First Prize in the LA Crime and Horror Film Festival, and her feature screenplays have received honors from the Austin Film Festival, Sundance Screenwriters’ Lab, and CineStory Foundation, among others. she has taught Creative Writing at Lehigh University and on Semester at Sea. An NEA fellow, she has published award-winning fiction and creative nonfiction in many print and online journals and anthologies.