Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

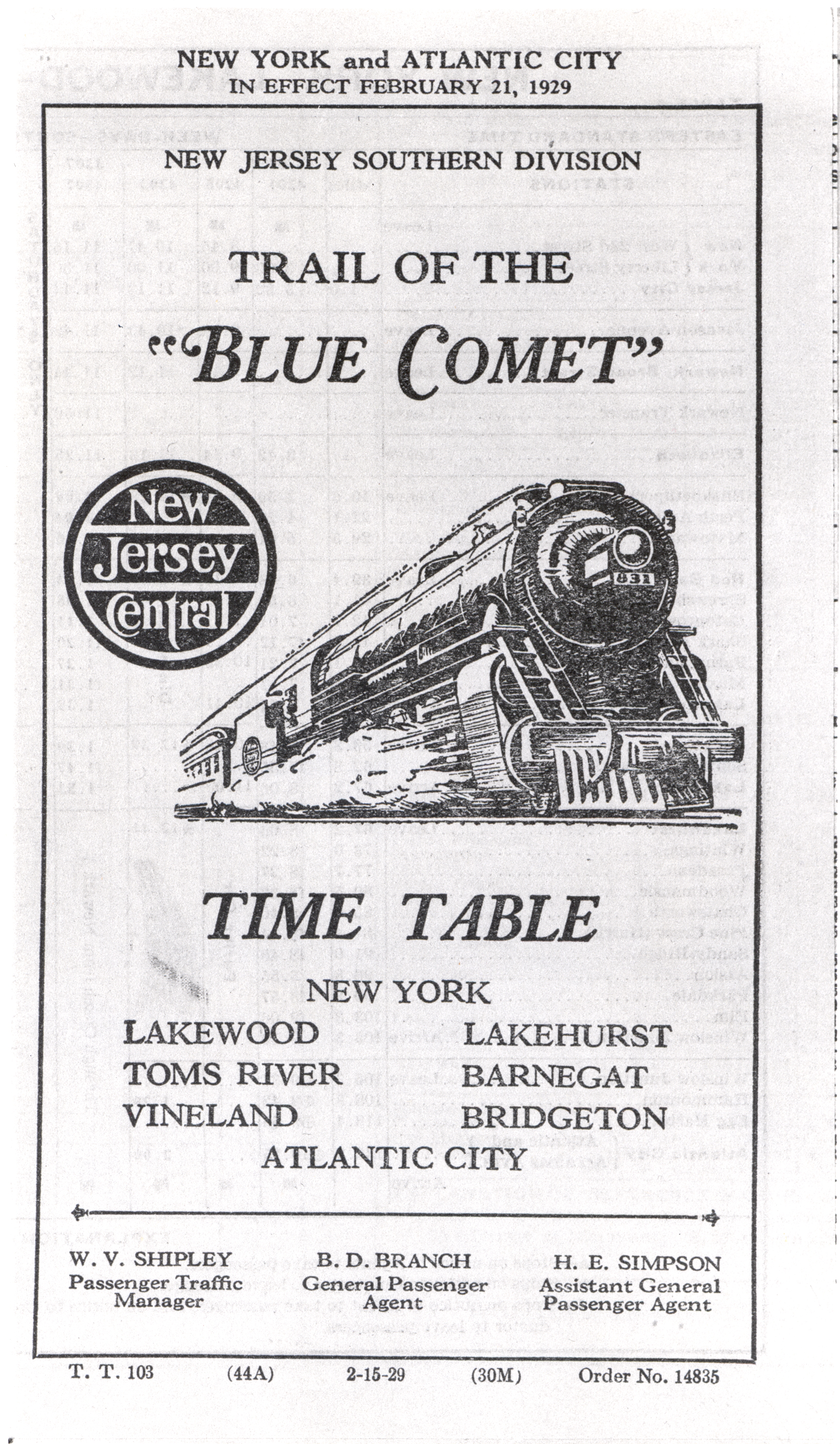

Courtesy of the Atlantic City Free Public Library’s archives

My novel opened at a train station, or at least it did, before my editor asked me to rewrite the beginning.

The story, which is set in Atlantic City in the summer of 1934, follows a Jewish family — not unlike my own — as they mourn the loss of a beloved daughter who drowned training to swim the English Channel.

“Have you ever considered opening the novel in a different setting?” My editor asked on a phone call the week the book went to auction. “Not at the train station. Maybe the beach?”

She was referencing Atlantic City’s Union Station, an eleven-track terminal that opened at the corner of Arctic and Arkansas avenues, in late June of 1934. The original terminal was built in 1854, when the island was just a spit of soft sand, at the corner of what would become Atlantic and South Carolina avenues.

I had considered several different opening scenes. Like so many first-time novelists, I’d written and rewritten those early pages. It’s hard to tell, until you get to the end of a draft, if you’re doing it right.

But never, in all those drafts, did I introduce my title character, Florence Adler, to readers in any location other than the train station. I was dying to work with this brilliant editor, but for some reason, the idea of cutting that scene from the manuscript left me heartbroken.

I argued, diplomatically, that I needed the train station for any number of reasons — to convey tone, to provide historical context, to bookend the story — but nothing I said to my editor on that first phone call got at how I really felt. To be honest, I’m not sure I even knew how I really felt.

A month later, when I received my editorial notes, I breathed out a sigh of relief. “I know we discussed over the phone the possibility of starting with a different opening,” wrote my editor, “but I’ve changed my mind.” The train station would get to stay.

Over the next several months, we made our way through three rounds of revisions. With each revision, the manuscript got better and the edits more granular, until I began to relax into them. No longer were we chopping scenes, or even sentences. In the margins of the document, we typed notes back and forth to each other about lobster salad and my blatant overuse of the word things.

In the margins of the document, we typed notes back and forth to each other about lobster salad and my blatant overuse of the word things.

When the manuscript was nearly letter-perfect, and I was certain that the train station would stay put, my agent called. “They’ve decided they want you to cut the first chapter,” he said. “To pick up the pace.”

All I could do was groan.

It can be hard to let go of good writing. There’s this expression, “Kill your darlings,” which was coined by Sir Arthur Quiller-Couch in his 1916 book, On the Art of Writing, but that has since been adapted by every writer from William Faulkner to Stephen King. Sometimes, we use it to reference individual words or sentences that are so florid they stand out, other times we talk about cutting entire scenes that, while beautiful to read, don’t advance the plot.

As a writer, I prided myself on being able to make merciless cuts. So, when, I wondered, had the train station become a darling I couldn’t kill? And why?

Partly, I blamed my own research, which was exhaustive and hard to let go of. On my computer, there was a file labeled “train” in which I’d amassed scores of photographs and timetables, maps and newspaper clippings. To go along with all that source material, I’d created a long document that carefully charted the consolidation of the Camden & Atlantic Railroad with the Philadelphia and Atlantic City Railway, the Philadelphia and Reading Railway and the Pennsylvania-Reading Seashore Lines. I’d visited the Atlantic City Free Public Library, where an archivist had helped me search for photographs of both stations, as well as other train-related ephemera. When I was in the throes of the project, I could have told you the cost of a ticket to Camden or where you needed to change trains to get to Salem — details that, if I’m honest with myself, never ran the risk of making it into the book.

The history of New Jersey’s rail network is a complicated one but, without it, I found it impossible to understand Atlantic City’s meteoric rise to prominence in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries — or my family’s place in it.

The history of New Jersey’s rail network is a complicated one.

As late as 1852, Absecon Island was a quiet barrier island, accessible only by boat. Just seven houses dotted its shoreline. A group of speculators saw the island’s potential — the chance to sell salt water and sea air as a health tonic to city dwellers — and bought up the land, simultaneously lobbying the New Jersey Legislature for a railroad charter to access it more readily.

The train went in quickly, spanning the Thorofare’s marshes as if it were a wide-winged shorebird. Speculators built a two-story excursion house to receive the train’s earliest passengers and got to work surveying the surrounding area, which they optimistically named “Atlantic City.” By 1860, the island boasted 700 residents and could accommodate 4,000 tourists a day. The first boardwalk — a skinny strip of wood — was built in 1870.

In 1876, the president of the Camden & Atlantic Railroad stepped down to establish the competing Philadelphia and Atlantic City Railway, and in a bid to undercut the competition, dropped fares from Philadelphia to Atlantic City from three dollars to a dollar and twenty-five cents. Suddenly, a trip to the shore became an affordable outing for the working classes. By 1888, more than 500 hotels and boarding houses had sprung up; on a busy weekend in the summer, crowds could eat the local establishments out of meat, milk, and bread.

The train was a moneymaker for speculators and a source of delight for tourists, but as I researched my novel, I became interested in what the train did for Jewish immigrants. My great, great-grandfather, Hyman Lowenthal, immigrated to the United States from Galicia and tried working as a peddler in Chattanooga before he caught a train to Atlantic City and never left. He opened a jewelry and pawn shop on the corner of Virginia and Atlantic avenues, was a founding member of Community Synagogue, raised six children in a house on States Avenue, and died in 1928, at the age of sixty, the year before his youngest daughter drowned.

My great, great-grandfather, Hyman Lowenthal, immigrated to the United States from Galicia and tried working as a peddler in Chattanooga before he caught a train to Atlantic City and never left.

Courtesy of the Atlantic City Free Public Library’s archives

My grandmother always called Atlantic City a Jewish town, and as I researched the city’s history, I came to understand what she meant. Atlantic City’s birth coincided, quite precisely, with the crush of Jewish immigrants, who had escaped poverty and persecution in Prussia, and later, Eastern Europe. Atlantic City was a new frontier, in need of a working class, and America’s Jewish immigrants were a working class, in need of a new frontier. For the price of a train ticket, they could start their lives anew.

“Everyone we knew was Jewish,” my grandmother once told me. When I scan old city directories, they tell the same story. Dannenbaum’s Bakery. Mayer’s Jewelry Store. Casel’s Delicatessen.

A 1918 survey of the United States’ Jewish population, conducted five years before my grandmother was born, found that, among small cities with a population of between 50,000 and 60,000 residents, Atlantic City’s Jewish population of 4,000 people was the largest. By the time my grandmother married, that number was closer to 10,000. My grandmother was eleven years old when the “new” train station opened. The Atlantic City Press described Union Station’s waiting room as large enough to “facilitate the handling of large crowds visiting the resort, particularly during the summer season.”

And for thirty or so years it did.

But by 1965, train ridership had begun to dip. America had fallen in love with the automobile and, during his presidency, Dwight Eisenhower had given the go-ahead on the construction of a system of interstate highways that would drastically reduce the time it took to drive from one place to another. Then there was air travel, which had become more affordable. People who once summered on the Jersey Shore could fly to Florida, the Caribbean, or even Europe with comparable ease.

In Atlantic City, a smaller passenger rail terminal was built on Bacharach Boulevard, and Union Station was converted into a bus depot. By 1997, the building was demolished to make room for the Atlantic City Expressway’s off ramps.

In recent years, passenger rail has experienced a renaissance. In fact, before COVID-19 curtailed Americans’ travel plans, the American Public Transportation Association had forecast that, in 2020, rail would account for more than fifty percent of all passenger trips on public transportation — surpassing travel by car and bus for the first time in decades.

But take a train to Atlantic City and you won’t find the Jewish community that once thrived there. Congregation Beth Israel moved to Northfield, and Community Synagogue eventually shuttered as families moved down the beach to the communities of Margate, Ventnor, and Longport. My grandparents met and married in Atlantic City but they left for better employment opportunities and never returned to the island to live.

But take a train to Atlantic City and you won’t find the Jewish community that once thrived there.

After I nixed the train station and rewrote the opening of my novel, I emailed the pages to my editor. In the email, I told her that I was almost prepared to admit that I liked the new opening better than the original one. The novel opens at the beach, and I’ll admit that the pacing is considerably improved.

Was I still a little sad to lose the train station?

Definitely.

Without the train, my story could never have begun.

Rachel Beanland is the author of the novel Florence Adler Swims Forever. She is a graduate of the University of South Carolina and earned her MFA in creative writing from Virginia Commonwealth University. She lives with her husband and three children in Richmond, Virginia. She has taught creative writing at the College of William & Mary and Virginia Commonwealth University and is the 2023 – 2024 Writer in Residence at the University of Richmond.