Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

Rome, found via Pixlr

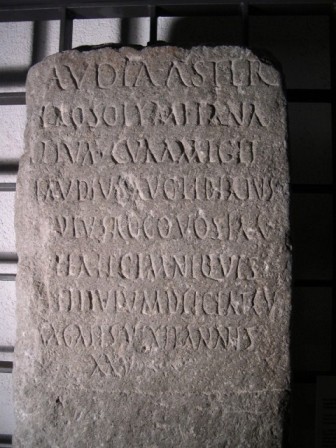

“Claudia Aster, captive from Jerusalem. Tiberius Claudius Masculus, freedman of the Emperor, took care (to set up the epitaph). I ask you, make sure that you take care that no one casts down my inscription contrary to the law. She lived 25 years.”

Epitaph for Claudia Aster

The inspiration for my historical novel, Rebel Daughter, was the two-thousand-year-old gravestone of a Jewish woman named Claudia Aster. Presumably, she was captured after the fall of the Second Temple in 70 CE and brought to Rome as a slave. Discovered in southern Italy, her gravestone was a major archaeological find, providing concrete evidence of both the existence of Jewish captives in Rome and a very unlikely romance.

In this ancient inscription, the Roman freedman Tiberius begs the reader to take care of the remains of the woman he loved. Although only a few Latin words are chiseled on the marble slab, historians and archaeologists have been able to piece together their remarkable story. They assume that Aster, or Esther in Hebrew, was sold in Rome after the failed Jewish rebellion against Rome, a time when the survival of the Jewish nation was at stake.

When I learned about the stone, I had to know more. How did a Jewish woman and a Roman man — whose peoples were fierce enemies — find each other? And how did they fall in love?

On the stone, the Latin word “captiva” confirms that Aster was captured in war, meaning she became a slave regardless of her previous station in life. Her first name, Claudia, is certain proof that Tiberius Claudius Masculus liberated her, since freed slaves were given the middle names of their former masters. Romans were not in the habit of commemorating their liberated slaves; this gravestone, which Tiberius erected, indicates a special connection between the two of them. Interestingly, from Tiberius’s middle name, we also know that he himself had been a slave at one time, and had been liberated by the emperor Claudius.

How did a Jewish woman and a Roman man — whose peoples were fierce enemies — find each other? And how did they fall in love?

From the epitaph, we also know that Aster died at the age of twenty-five, which was below the legal age for manumission. According to Roman law, it was illegal to free slaves under the age of thirty, except in very specific circumstances. The only exception that could conceivably have applied in this case was marriage, and the only plausible reason for their marriage was love. As her owner, Tiberius would legally have been entitled to have Aster perform any kind of work for him. For example, he could have had children with her as his concubine. Of course, Tiberius could have freed her just out of kindness. But it seems likely that he loved her and wanted to have legitimate Roman children with her. That, according to scholars, is the most logical interpretation of these two-thousand-year-old words.

I spent more than ten years researching the period in which Aster’s story — and that of the tragic fall of Jerusalem — unfolded, consulting with some of the world’s leading scholars and archaeologists along the way. I felt an obligation to the real-life individuals to bring their story to life as accurately as possible. Aster, Tiberius, and Josephus (an ancient Jewish Roman historian, and also a character in the novel) were eyewitnesses to, and participated in, events that permanently altered the course of history. They survived the destruction of Jerusalem, which forever changed Judaism from a Temple-based to a community-based religion centered in the synagogue and beth midrash, or house of study. Their struggle for survival, freedom, and love is still relevant today, as so many people around the world are caught in war zones. And unfortunately, the civil discord and religious fanaticism of the first century are issues we’re still facing.

In many ways, I didn’t find Esther’s story. Her story found me. Rebel Daughter is my attempt to tell it. But even after years of research, we can never really know what happened. What we do know for sure is that Esther and Tiberius were two people who weren’t supposed to find each other, but did. I hope you find their story as compelling as I did.

As soon as she learned of the first-century tombstone that inspired Rebel Daughter, Lori Banov Kaufmann wanted to know more. She resolved to bring this ancient love story to life. Before becoming a full-time writer, Lori was a strategy consultant for high-tech companies. She has a BA from Princeton University and an MBA from Harvard Business School. She lives in Israel with her family.