Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

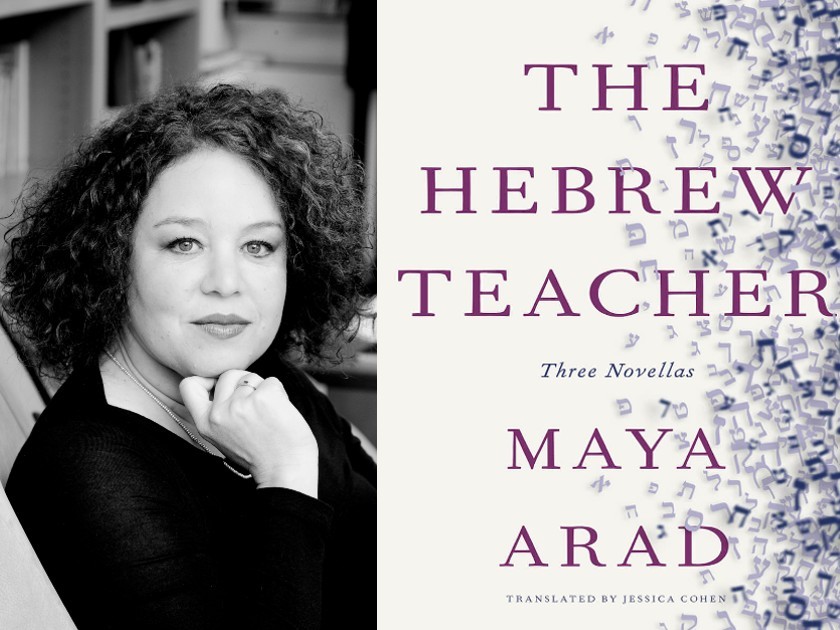

Author photo by Mira Mamon

Ranen Omer-Sherman speaks with Maya Arad about her book The Hebrew Teacher, newly translated into English and out from New Vessel Press. Omer-Sherman and Arad discuss the experience of Israeli expatriates in the US, academia and aging, and the evolution of Hebrew literature.

Ranen Omer-Sherman: It is such a pleasure and an honor to have this exchange. You are highly regarded by so many of my colleagues (and critics!) not only as the most accomplished Hebrew writer living outside of Israel but one of the best of all contemporary Israeli novelists. The Hebrew Teacher offers such deeply affecting portrayals of various forms of estrangement, missed connections, and distances. I’m aware that in much of your earlier work you didn’t tackle the experience of Israelis living in America in such a sustained way. When did you first realize that you were ready to shift your focus from Israel to the lives of expatriate Israelis? Have you reached the point where you felt you had less to say about Israel or were you simply more drawn to the latter?

Maya Arad: I think my work has always touched on the possibility of living outside Israel. But it’s more than that: it was living outside of Israel that made my work possible. My first book was a novel in verse, Another Place, a Foreign City. It had to be written in “a foreign city” (Cambridge, Massachusetts, and Geneva, Switzerland, where I was living at the time). It made no sense within the terms of contemporary Israeli literature and I wrote it in complete isolation from any literary scene. And so it’s quite natural that it ends (mild spoiler) with the protagonist moving to Vancouver. Weirdly, that book became a success. The Israeli reading public wanted this different angle.

It would be fair to say that over the years, the experience of Israeli expatriates in the US has moved from the background to the foreground of my work. I don’t think there was a point when I decided, consciously, that I have less to say about Israel. It’s true that as I spent more time in the US I found that there are so many stories to tell about Israelis living in California – an entire Comédie humaine, and I had so many ideas for books I wanted to write. I do remember, though, a point where this decision became more conscious: after I published the novel Master of the Short Story (2009), about the life and work of a writer living in Israel, people came to me and said, Wow, I would never have guessed you don’t live in Israel. It was meant as a compliment, and I thought: is it really a compliment? Do I want to pretend I am living in Israel? To ignore the fact that my life is based in the US? The novel I published right after that book, Suspected Dementia (2011), about an elderly childless Israeli couple living in California, puts immigration and expatriate life at its center.

I should add that this is a relatively new thing for Hebrew literature. When I was growing up, there were no Hebrew writers outside the US that I knew of, and Hebrew literature itself was geographically largely contained within the borders of Israel. I didn’t come across characters who were Israeli expatriates in the books I read when I was growing up, except one or two examples of yordim (the derogatory name for Israelis who left Israel), who were often presented as miserable and uprooted. But it’s not so much about ideology as about geography. Israeli culture was really focused on the Israeli space. Perhaps the best example is one of the finest Israeli films which came out in 1972, But Where Is Daniel Wax? (directed and written by Avraham Heffner). It’s about a visit to Israel by an expat musician, Benny Spitz. The film literally ends, in one of the most famous scenes in Israeli cinema, with Spitz on his way back to the US, riding up the escalator beyond border control at Ben Gurion Airport. The Israeli imagination ended there. I am so glad that is no longer the case. There are now quite a few Hebrew-speaking authors who live in Europe and the US.Recently there’s been an abundance of books that deal with the Israeli experience in the US. The Wolf Hunt by Ayelet Gundar Goshen, Hunting in America by Tehila Hakimi, Big Fish by Ruby Namdar, to name a few. I don’t take it for granted that I can have my books published and read in Israel while I live in the US, and I feel very fortunate that I came of age as a writer at a time when Hebrew literature has expanded its coverage (both geographically and metaphorically) beyond the land of Israel.

ROS: I especially admire the way you successfully navigate having gentle fun with recognizable sociological types while retaining the complex humanity of all of your characters in the captivating complexity of the three novellas that compose The Hebrew Teacher. You seem to be that rare kind of writer who achieves the fraught balancing act of including both pathos and comedy. But do you ever find yourself asking if you’ve gone too far in your characterizations and forcing yourself to pull back a little?

MA: I’ll answer this one very briefly. Usually, the work required in editing is the opposite of what you describe. Believe it or not, I find it hard to be cruel to my characters and often I re-read and realize I did not extract all the comedy and pathos I could out of the situation, and that I need to add to the unpleasantness. This usually makes characters more human, not less; more realistic, less caricatured. People are awkward, and my job as a writer is to look at that without flinching.

ROS: In thinking of the title story, I felt that those of us in academia cannot help worrying about the fate of Hebrew studies in the university. Even before the current war, things seemed precarious. As your poignant protagonist, Ilana, reiterates, “It wasn’t a very good time for Hebrew.” It seems so woefully representative of our inauspicious cultural moment. Does that mournful sentiment express where you see things going?

MA: Mournful sentiment is my middle name. People often mention this in relation to my writing. Sometimes they call it nostalgia. But to the question itself, yes, of course enthusiasm for Hebrew learning is diminishing, but so is enthusiasm for Russian, Italian, literature, history, philosophy, and so much more. My husband, a professor of Classics, thinks of The Hebrew Teacher as an elegy to the humanities in American research universities. I wrote about Hebrew because this is what I know and what I feel close to, but I think it’s just a special case of a process we see all over, in academia, literature, and other areas too. And this, of course, is not happening only in America. As a Hebrew writer, I feel the difference between the status of literature when I was a reader, growing up in the 1980s, and today. Literature used to be the crown jewel of Hebrew culture. It had a special status, perhaps undeservedly, that other forms of art didn’t have. Things are different today – literature is less prominent than other forms of art, and people read less than they used to. This is the place where I feel a deep connection with Ilana, although in many other ways we couldn’t be more different: something we care deeply about (whether it’s Hebrew instruction or literature) is being marginalized, and there’s little we can do about it.

So, for me, “The Hebrew Teacher” is on one level a topical story about the status of Hebrew in American universities today, but on another level it’s a story about growing old and seeing your life’s work losing relevance in today’s world, and this is the level I am more interested in.

“The Hebrew Teacher” is on one level a topical story about the status of Hebrew in American universities today, but on another level it’s a story about growing old and seeing your life’s work losing relevance in today’s world.

ROS: I think that for many readers, Ilana in “The Hebrew Teacher” is such a recognizable and even beloved figure. Born in 1948, the year of the founding of Israel, she has a seemingly endless reservoir of enthusiasm for immersing her students in Israeli culture, or at least that of Arik Einstein and the past generations she knows intimately. But after forty years of working in the trenches she remains an adjunct and her colleagues are eagerly moving ahead with the hire of her least favorite candidate, the distinctly non-Zionist Yoad, who neither shares her enthusiasm for Hebrew literature or Israel itself and is in fact an active proponent of BDS. He refuses any contact with Hillel or Jewish adult learners in the community and seems to have only contempt for her. Though his cringe-making research on “Heidegger as a Jewish writer” might seem to some readers like near parody, this character in fact seemed all too real to me, a character I recognize from my own institution. Is his extreme advocacy of anti-Zionism something you see transforming the nature of Jewish and Hebrew studies? Presumably, things are healthier at Stanford University where you are Writer in Residence at the Taube Center for Jewish Studies. Just how does the atmosphere and morale feel lately in your sphere of academia?

MA: I feel fortunate to be at the Taube Center for Jewish Studies at Stanford. And, in general, I feel supported by the Stanford administration. I do feel the shockwaves, however, through my eldest daughter, who is an art student at Cooper Union in New York and must deal with very unpleasant anti-Israeli and antisemitic harassment, in a few cases directed at her personally.

“The Hebrew Teacher” was written not long after Operation Protective Edge in Gaza, in 2014. I remember thinking for a moment, after October 7, that this story had become irrelevant – the words “war in Gaza” have now taken on such a horrific new meaning. But in fact the opposite happened: people find it more relevant than ever to the current experience on college campuses. Perhaps literature does have a way of being prescient. There is the sense of Ilana’s shock, of no longer having a minimal shared worldview between her and people on the far left like Yoad. But I think the story tried to capture something a bit more complex than just a political and ideological battle between two rival sides. The story is told from Ilana’s point of view, which is very Zionist and pro-Israeli. But we see that there are moments where she is in agreement with Yoad on certain issues, and she is also portrayed, through some parts of the story, with a certain irony. We know that the world is complex and that sometimes the Yoads of the world have valid points, sometimes the Ilanas do, and most of us have both an Ilana and a Yoad struggling inside each of us at any given moment. Most Israeli expats, especially in academia, find themselves these days oscillating between anger towards the American far left and anger towards Israel, with the one constant core being the love of the Hebrew language and culture that we share. That’s probably Yoad’s one fatal flaw, from the point of view of the story – he doesn’t care about Hebrew literature!

ROS: How often do you visit Israel these days? Have you been back since the October 7 atrocities? I read somewhere that you spent your early years on Kibbutz Nachal Oz (I used to have family there too), which was one of the communities so viciously attacked by Hamas. Were any of the people you grew up with victims of that assault? Friends of mine lately have been saying Israel is now almost unrecognizable, so pervasive is the level of gloom and despair. Are you optimistic that the society will eventually recover its former confidence, optimism, and tenacity?

MA: I remember seeing, sometime in September, that Kibbutz Nahal Oz, where I grew up, was planning to celebrate its seventieth anniversary on October 7 and thinking, I wish I could be there. I have such fond memories from the thirtieth anniversary celebration that I attended as a child. Then of course this celebration never happened. Naturally, I know quite a few of the victims and those kidnapped. Some of my classmates lost their parents or children. My sister’s classmate was murdered with her entire family, only the youngest child being spared. I haven’t been back to Israel since October, but I also hear of gloom and despair everywhere. I grew up in the shadow of the trauma of the Yom Kippur War, but my parents, who were adults at the time, tell me that 1973 felt like nothing in comparison with this.

You ask if I’m optimistic. Oy, have you got the wrong number… Optimism isn’t my strong suit. If anything, I am the opposite. In 1996, while I was a graduate student in the UK, I went to Israel to vote. That was when Netanyahu was elected for the first time. The shock was so great – I couldn’t imagine that only a few months after Rabin was assassinated, the person who incited and – in my view – helped bring about the murder – was elected – that I felt something was irretrievably broken that day. That was the point when my husband and I decided not to go back to Israel, and we ended up in California. One of the good things about being a pessimist is that you are sometimes pleasantly surprised, but sadly, in this case, I was right. Things have been going from bad to worse for years, and October 7 was just a quantum leap. To answer your question – October 7 was a life-changing event that happened very recently. I’d be a complete fool if I were to make predictions about whether Israeli society will eventually recover. What does “recover” even mean in the aftermath of October 7? I think things will have to change. Hopefully for the better, but, as I said, I am a pessimist…

ROS: “Make New Friends,” the alternatively scorching and tender family drama that concludes the book, bears so many rich psychological insights when it comes to parenting in the time of cellphones and the cruelties of middle school. I’m a parent of two so it also felt like it must have come from achingly personal experience. Did you experience anything like the angst and overprotectiveness that drove Efrat, your protagonist who defiantly crosses the line?

MA: You’d be surprised, but the seed for this story was planted years ago, when my daughter was a toddler and social media was still toddling as well. In 2006, I read an article about a thirteen-year-old girl, Megan Meier, who committed suicide after being harassed online by a boy she met in a chat room. It later turned out that it was an adult woman in her fortieswho pretended to be that boy. She was the mother of another teenage girl, to whom Megan Meier had been mean at school. This was her revenge. I couldn’t stop thinking about that, but as a writer, you can’t just decide “now I will write this story.” It somehow has to come naturally to you. And it never did. And then my older daughter started middle school and all of a sudden this story was the most natural thing to write. But the truth is, at its core, this is not a story about middle school social life. It’s a story about people realizing their own limits, which is a universal experience that is made very palpable through becoming a parent. We wish to be able to provide everything, and we usually bungle it.

ROS: You write with such compassion and insight when it comes to the disappointments of aging characters, especially your portraits of older women and their relationship to the past. Are there any classic portrayals of women in world literature you find yourself revisiting? And when it comes to rendering the challenging psychology of aging, do you feel that you’ve become a better writer over time?

MA: Alison Lurie and Barbara Pym are two authors I love, who often write not so much about old age as of late midlife, that point when you’re old enough to realize your dreams won’t come true, but still have a long time ahead of you to mourn those unfulfilled dreams. I’ve read Foreign Affairs by Lurie four or five times. Its protagonist, Vinnie Miner, a fifty-four-year old single woman who is described as “homely” and “elderly” and portrayed as selfish and even unkind. I just admire Lurie’s ability to create a character that is so unlovable, yet so touching.

I wrote Suspected Dementia, about a California-based Israeli couple in their late sixties, when I was in my late thirties. I tried to imagine what life would look like thirty years from then. In retrospect, I think I was about to enter midlife, writing about a couple who are at the very end of that stage and about to enter their elder years, and I used my own experience of transitioning through life to write it. I am now mid-way between those two stages, so I am slowly getting closer in age to my characters and at some point I will know if I got it right. Regarding the other question, I am in no position to testify about my own work. I’ve been a published writer for more than twenty years, and I do feel more experienced now. There are mistakes I made in the past that I wouldn’t make today. But I wonder if I also lost something along the way – being fearless, daring to be more experimental, not feeling obligated to live up to readers’ expectations. As I said, it’s not for me to say.

ROS: Another lifetime ago it seems, I was a former combat soldier. Where I live, I’ve often been asked to speak to the media, also community groups, about recent horrific events. Sometimes those occasions are highly charged. Late last year I spoke at an interfaith gathering at a church before a predominantly Arab and Muslim audience and things got a little rough. The most jaw-dropping moment came when a Jewish leftist of my acquaintance stood up to deny that the atrocities of October 7 even occurred. How difficult are conversations in your world currently? In your position, are you ever pressed to take positions on Middle Eastern politics, and if so, what have you been saying or thinking lately?

MA: I feel that my world has turned upside down. Often I don’t know what to say and I don’t know what to think. And that’s okay with me. In fact, I am quite suspicious of people who are certain beyond any doubt about their beliefs currently. My fundamental beliefs – that everyone has the right to live in peace and dignity – have not changed. But it’s going to be a lot more difficult now to implement this in practice. I feel that people like me are currently under attack on several fronts: Hamas and its atrocious terrorist acts of October 7, the far left which minimizes or completely ignores Israeli victims, and the current Israeli government, the worst the country has ever had, which makes it extremely difficult to defend Israel’s acts. So, as you can imagine, I have many conflicting thoughts and ideas that are not always compatible with each other, and if I don’t have to, I don’t say anything. As the Bible says, “Therefore the prudent keep quiet in such times, for the times are evil.” I do not initiate conversations. When I am confronted with a blatant denial of facts (like the pro-Palestinian activist who denied that Hamas terrorists committed rape but claimed that hundreds of Palestinian women were raped by IDF soldiers on October 7), I stop the conversation immediately. There is a limit to what I can deal with. Most people are sympathetic to what Israel went through, and express sadness about the human lives lost on both sides, with which I certainly agree.

ROS: You’ve been living outside Israel since 1994 and in this country since 2002. Do you read more in Hebrew or English these days? Are there novelists or other writers working in Israel today that you especially admire? And in developing your own craft, have you been more inspired by writers in Hebrew or other languages?

MA: I read some English, but mostly Hebrew. Partly it’s because I read Hebrew about five times faster than English, making it so much more convenient and rewarding to read Hebrew. But mainly it’s because I’m a Hebrew writer, and I like to keep up with what’s being written in Hebrew. I recently came to realize that it’s not just that I happen to write in Hebrew, I am part of Hebrew literature. That’s what I grew up reading, that’s how my writing was shaped. If my brain were to be rewired and my mother tongue changed into English overnight, I still wouldn’t be an English writer in the sense that my upbringing, my sensitivities, my whole world, were formed within Hebrew literature. I once served as a judge in a short story contest for students writing in English, along with two other Jewish American writers. Things they found insensitive I found harmless, other things I thought were cliched they thought were touching. It could be just a difference between people, but I felt it also had to do with us coming from very different cultural backgrounds and literary contexts. I have many writer friends in Israel whose work I love and admire – too many to mention here, so I’ll just pick two women writers who are also close friends: Ayelet Gundar Goshen, whom I mentioned already for The Wolf Hunt, and Noa Yedlin, whose novel, Stockholm, came out in translation last fall in the US. I could mention many authors I love and read extensively, but it’s hard for me to tell who inspired me – that is for other people to observe. Writers I go back to again and again are the Israelis Aharon Meged (a wonderful Hebrew writer, author of many books I love, including the 1965 Great Hebrew Novel The Living on the Dead) and the playwright Hanoch Levin; the Russian writers Nabokov and Tolstoy; and then Lurie and Pym, mentioned above.

ROS: Finally, I suspect that readers of The Hebrew Teacher, so elegantly translated by Jessica Cohen, will find your playful and unpretentious voice utterly irresistible and will wish to seek out more. You have eleven books of Hebrew fiction including a recent mystery novel set in California. So obviously your English readers have just reached the tip of the iceberg when it comes to your highly acclaimed books. Are there current plans for future translations that you can share? And are your works out in other foreign versions? And given your enormous popularity among the Hebrew readers I know, not to mention your prolific output, do you have any ideas about why you’ve only just begun to be translated?

MA: It’s a very good question. The short answer is, I don’t know. It’s always a mystery why some books get translated and some don’t (or, for that matter, why some books sell and some don’t). Jessica Cohen, the book’s wonderful translator, once shared with me her theory that when publishers consider books in translation, they are looking for something extra, something specific to the language and culture of that book. There are enough English novels about marital strife or midlife crisis – no need to translate any more of those. In the case of Hebrew literature, this means that it’s books about the Kibbutz, the IDF, or the Holocaust that tend to get translated. I am so thrilled that New Vessel Press decided to publish The Hebrew Teacher, and I can now share that my most recent novel, Shanim Tovot, will be published in 2025 by New Vessel under the title Happy New Years.

Ranen Omer-Sherman is the JHFE Endowed Chair in Judaic Studies at the University of Louisville, author of several books and editor of Amos Oz: The Legacy of a Writer in Israel and Beyond.