Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

Cover image: University of Pennsylvania Press, Copyright © 2020.

Firecrackers burst into the air and zigzagged erratically across the ground. Masked revelers poured into the streets. Men, women, Christians, Jews, enslaved and free, filled the air with the chaotic sounds of shouting and singing. Adults and children donned “indecent” costumes, some beating drums. The pungency of intoxication wafted through the tropical breezes. No, this was not the commemoration of national independence, a marking of the end of war, or New Year’s Eve in a pleasure garden. This was the Jewish holiday of Purim, as celebrated in the Dutch Caribbean two centuries ago.[1]

Purim is a minor holiday that commemorates the overturn of a decree of genocide against the Jews of Persia in the fifth or fourth century BCE, plotted by the villainous Haman. Drawn from the biblical Book of Esther (the only volume of the Hebrew Bible that does not contain the name of God), the holiday falls on the fourteenth day of the Hebrew month Adar, variably coinciding with late February, March, or April of the Christian calendar. Preceded by the “Fast of Esther,” Purim is commonly observed for one day throughout the Jewish diaspora and is typically marked by spirited merriment that encourages inebriation and masquerade. In the Dutch colonies of Curaçao and Suriname, however, Purim lasted up to two weeks. It created so much ruckus among its multiethnic celebrants that both synagogue authorities and the local government curtailed its celebration starting in 1775.

The ecumenical celebration of Purim is not wholly unusual in Jewish diasporic history. In early modern Italian cities, for example, Christians and Jews danced the night away in the world’s first ghettos, their masks and mixed dancing flouting church-imposed separation between the two faiths. But unlike elsewhere, most Purim carousers in the Dutch Caribbean were enslaved people of African ancestry. Both Suriname, located on the South American mainland just north of Brazil, and Curaçao, an island off the coast of Venezuela, were slave societies.

A slave society, as opposed to a society with slaves, was fundamentally reliant on unfree labor. Were slavery to have been abolished or slaves suddenly expelled, killed, or freed, the entire economy would have collapsed. In such societies, slavery informed every aspect of life, from religion and language to sartorial norms and leisure activities. Both Suriname and Curaçao were overqualified for the label of slave society, with upwards of ninety and sixty percent of their populations, respectively, in chains.[2] In each of these colonies, Jews formed from one to two thirds of the white population and enjoyed political privileges collectively unparalleled in the Jewish diaspora, including the liberty to convert select slaves to Judaism. If slavery was an unavoidable fact in these Dutch colonies, so was Jewishness.

Purim is a vivid example of the entanglement of Jews with the majority population. Purim in these two colonies rivaled all major holidays of the Jewish calendar, including the Day of Atonement. In Suriname’s two Portuguese synagogues, more candles were illuminated on that holiday than on an ordinary Friday night — a brilliant display of forty-eight lamps and four tapers. The colony’s annual almanac, published beginning in 1789, frames Purim as the most prominent Jewish celebration, citing it first in a list of Jewish holidays. Aside from Tisha B’Av, it is the only minor Jewish holiday consistently mentioned in that periodical. Among the colony’s Jews, privately owned biblical scrolls were invariably the Pentateuch, but the Book of Esther was a notable exception. Among their owners was a Eurafrican Jewess called Roza Mendes Meza. Born a slave, the wealthy Meza listed in her 1771 inventory a Historie van Hester.

Purim in these two colonies rivaled all major holidays of the Jewish calendar, including the Day of Atonement.

As her library suggests, the ancient narrative was important to Surinamese people of African descent. In 1759, a “Jewish negro” belonging to the Portuguese Jew Joseph, son of Abraham de la Parra fled into the rainforest, carrying a “so-called History of Esther in Hebrew.” A government expeditionary force soon located the rolled parchment among the huts of Maroons, enslaved Africans who absconded to the colony’s interior and founded their own autonomous communities. Did this refugee regard the object as a talisman to protect him from capture, or did he aim to inflict financial and emotional distress on his master? Perhaps he stole the scroll as a reminder to his owner that the fates of perpetrators and victims were abruptly inverted in the biblical narrative’s denouement.

Other slaves of African descent could identify even more strongly with the Jewish holiday. Purim was the only Jewish holiday imposed as a slave name by Jewish masters across the Caribbean. The most visible of these Purims was a native of Suriname who labored as a sawyer in the Jewish village of Jodensavanne (“Jews’ Savanna”), some thirty miles south of the capital city of Paramaribo. In the 1770s, this man caused an uproar by attacking both fellow slaves and members of the slaveholding Jewish community. On one occasion, he murdered a bondman charged with keeping order among slaves during the synagogue service. The following year, he physically and repeatedly threatened a Portuguese Jew named Jacob Cohen Nassy in the presence of multiple witnesses. By all counts, Purim was acutely aware of the significance of his name. His actions coincided with the weeklong festivities of the Jewish holiday. By then, most of the village’s residents had complained about him on various occasions. Purim was ultimately whipped and banished from the Jewish village, only to return in 1782.

By all counts, Purim was acutely aware of the significance of his name. His actions coincided with the weeklong festivities of the Jewish holiday.

That year, Purim roiled the village once again. A resident discovered “the negro Purim” slaughtering a goat, later identified as the property of one Isaac Lopes Nunes. When Meza attempted intervention, Purim violently resisted. The communal minutes do not detail Purim’s motivation in killing the quadruped, but it is possible that he was sacrificing the animal to a god, or in veneration of one of his ancestors, a practice common to many communities in Angola and other regions of West Africa where Purim likely traced his ancestry. Purim would have had numerous occasions to appeal to higher powers for intervention or protection, starting with his periodic subjection to physical discipline. One Portuguese Jew, tasked with administering corporal punishment, later testified that he “was exhausted from” giving Purim “a severe beating.” By this time, Purim had already witnessed several slaves owned by his mistress released from bondage after her death and probably realized how slim his own chances were as a “negro” man, as opposed to the “mulatto” women and children so often favored in manumission cases. Purim must have understood the inevitability of severe corporal punishment, as well as a second banishment from the Jewish village that threatened to be worse than the first. Yet did not the holiday of Purim teach one to hope for sudden, unforeseen salvation?

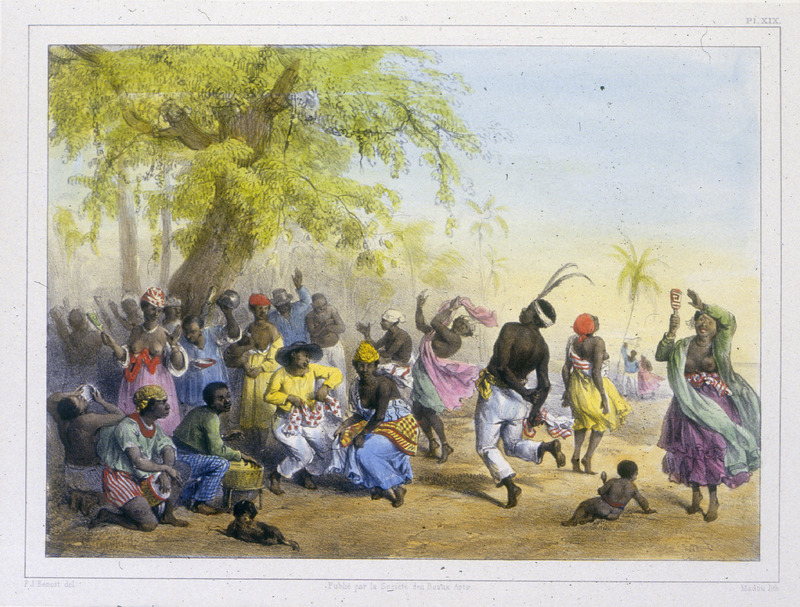

Slave participation in Jewish religious life in the colony was likely a constant — as legislation attempting to curb such involvement suggests. Slaves owned by Jews sometimes incorporated a Portuguese Jewish cultural worldview into their own. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the celebration of the Purim holiday itself. As early as 1711, Suriname’s colonial legislators complained of the great numbers of slaves in Jodensavane who gathered on Jewish holidays to “drum, dance, and play,” activities that caused “many disorders.” But in the capital city of Paramaribo, these celebrations were much more exposed to the public than downriver in the Jewish village of Jodensavanne. Starting in 1775, the colonial government issued successive edicts banning outdoor celebrations of Purim in the city. By 1807, these decrees had entirely lost their efficacy and the disruption was worse than ever. Not only had the merrymakers walked up and down the avenues “very indecently with masks,” but they had also paraded in decorated military costumes, to the beat of drums, sounding an alarm, an act forbidden by a colonial placard. Moreover, some male Jews donned “inappropriate and indecent costumes,” parading “almost naked and in the form of Indians and Bush Negroes” through the streets. The enslaved were among the most enthusiastic participants, circling the Jewish celebrators and pulling wagons laden with costumed Jews and their domestic bondmen, their shouts and singing reverberating through the city.

“Le Dou, ou grande fête des esclaves” (“The Dou, or Great Festival of the Slaves”), figure 38 in Pierre Jacques Benoit, Voyage à Surinam; description des possessions néerlandaises dans la Guyane (Bruxelles: Société des Beaux-Arts de Wasme et Laurent, 1839).

What, then, did Purim celebrations mean to Suriname’s multiethnic enslaved population? In early modern West Africa, masquerades and communal dances constituted crucial life-cycle rituals, including initiations. Taking part in masked Purim celebrations may have been a means by which slaves could inculcate ancestral values to their immediate community and transmit those to their descendants. Until it was outlawed, Purim carousing may have served as a sanctioned outlet through which slaves could invoke or refashion their ancestral masquerade and communal dance traditions. Alas, communal records do not record the motivations of African-descended roisterers. But it is clear that by the last quarter of the eighteenth century, Purim had become a joint cultural production with strong West African overtones, an Afro-Surinamese festival akin in many ways to what scholars and several contemporary observers in the Caribbean have understood as local varieties of Carnival. By the 1800s, Purim in Suriname had become the patrimony of Suriname’s ethnically diverse population. Its denouncers could do little more than reissue ordinances that had been ineffectual since the eighteenth century, when the joyful celebrations of Jews and African-origin slaves first began to converge.

[1] On the social function of fireworks in early modern Europe and its colonies see Simon Werrett, Fireworks: Pyrotechnic Arts and Sciences in European History (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010).

[2] Ben-Ur, Jewish Autonomy in a Slave Society, 5, 335n159 (late eighteenth century).

Copyright © 2021 Aviva Ben-Ur.

This synopsis is generalized for readability. For specific details see chapter 6 of Aviva Ben-Ur, Jewish Autonomy in a Slave Society: Suriname in the Atlantic World, 1651 – 1825 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2020) and “Purim in the Public Eye: Leisure, Violence, and Cultural Convergence in the Dutch Atlantic,” Jewish Social Studies 20: 1 (Fall 2014): 32 – 76. This synopsis is published with permission of the University of Pennsylvania Press, Jewish Social Studies, and Indiana University Press.

Aviva Ben-Ur is Professor in the Department of Judaic and Near Eastern Studies at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, where she holds adjunct status in the Department of History and in the Programs of Spanish and Portuguese, and Comparative Literature. She is the author of Jewish Autonomy in a Slave Society: Suriname in the Atlantic World (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2020).