Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

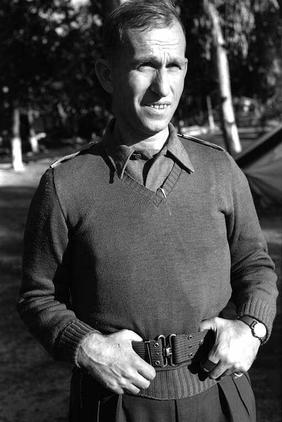

Chaim Sheba, a surgeon general of the Israeli army and later the director general of the Israeli Ministry of Health, was also a colorful, pioneering Israeli geneticist. Early in his career, Sheba stumbled into human genetics in the process of preparing to practice medicine in his adopted country. Born in Austria, he left for Palestine with a “still wet” medical school diploma from the University of Vienna expecting to “dry the uninhabited swamps.” Drying the swamps was a way to eliminate malaria, a disease common not only in Palestine, but throughout the coastal Mediterranean basin. While on the boat to Palestine, Sheba read a book about tropical diseases and learned that one of the major complications of malaria was blackwater fever. Typically, the “black water” urine of individuals with red blood cells disrupted by malarial parasites contained the dark-colored breakdown products of the oxygen-carrying protein, hemoglobin.

Chaim Sheba, a surgeon general of the Israeli army and later the director general of the Israeli Ministry of Health, was also a colorful, pioneering Israeli geneticist. Early in his career, Sheba stumbled into human genetics in the process of preparing to practice medicine in his adopted country. Born in Austria, he left for Palestine with a “still wet” medical school diploma from the University of Vienna expecting to “dry the uninhabited swamps.” Drying the swamps was a way to eliminate malaria, a disease common not only in Palestine, but throughout the coastal Mediterranean basin. While on the boat to Palestine, Sheba read a book about tropical diseases and learned that one of the major complications of malaria was blackwater fever. Typically, the “black water” urine of individuals with red blood cells disrupted by malarial parasites contained the dark-colored breakdown products of the oxygen-carrying protein, hemoglobin.

When Sheba arrived in Palestine, he learned about an unexpected springtime occurrence of blackwater fever caused by eating fava beans, a popular Mediterranean delicacy. Favism had been known in ancient Greek times with Pythagoras, Diogenes and Plutarch all warning about the dangers of eating fava beans. Eating the beans or even smelling the pollen caused a sudden illness of abdominal pains and vomiting, followed by pallor, jaundice and brown-colored urine – all resulting from the rapid breakdown of red blood cells. During the 1930s, all of the patients that Sheba observed with favism were Jewish males of Iraqi, Yemenite or Kurdish origin. During World War II, while serving as a surgeon in the British Army, Sheba observed men who experienced severe breakdown of red blood cells resulting from ingestion of the newly developed antibiotic and anti-malarial drugs. These reactions occurred primarily among Iraqi, Turkish, Greek, Yemenite and Kurdish Jewish soldiers, and were also common among non-Jewish Greek and Cypriot soldiers, and Italian prisoners of war. To Sheba, it was striking that Ashkenazi Jews did not share these sensitivities that were prevalent among their co-religionists.

The reason for this difference between the Ashkenazi and other Jews became apparent after the war — an inability to repair damage to red blood cells that resulted from exposure to agents that were non-toxic to the majority of the population. This inability occurred in individuals who are deficient for the enzyme, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD). As its name would suggest, G6PD normally breaks down the sugar, glucose, and, in the process, generates an antioxidant that repairs red blood cells. Although G6PD is produced and used by all of the cells of the body, only red blood cells are sensitive to the effects of oxidizing agents. The enzyme is encoded by a gene on the X chromosome and men who carry a mutant gene on their single X chromosome are susceptible to these exposures. Women who have two copies of the X chromosome are relatively resistant to this condition when one of their X chromosomes carries a mutant G6PD gene.

Over time, Sheba recognized that other genetic diseases (Tay-Sachs, Gaucher, familial Mediterranean fever) were found almost exclusively within certain Jewish groups, reflecting the unique history of those groups. He assumed that these diseases were caused by transmission of a mutant gene that occurred sometime in the distant past, and then transmitted by a group of “founders” who migrated to that site of the Jewish Diaspora. This phenomenon has come to be known as a “founder effect.” Sheba was fond of using Biblical genealogies and spoke of conditions being transmitted by the descendents of the sons of Noah or other, later Biblical characters. Thus, Sheba established the notion that these diseases serve as genetic markers for the populations in which they occurred. Although not all of the members of the population carried these mutant genes, enough do to recognize a shared genetic legacy.

Dr. Harry Ostrer is the author of Legacy: A Genetic History of the Jewish People. He is a medical geneticist who investigates the genetic basis of common and rare disorders. He is also known for his study, writings, and lectures about the origins of the Jewish people. He is a professor of Pathology and Genetics at Albert Einstein College of Medicine of Yeshiva University and Director of Genetic and Genomic Testing at Montefiore Medical Center.

Harry Ostrer, M.D., is the author of Legacy: A Genetic History of the Jewish People. Dr. Ostreris professor of pathology and genetics at Albert Einstein College of Medicine and director of genetic and genomic testing at Montefiore Medical Center. He previously served as director of human genetics at New York University School of Medicine.

Joseph Jacobs: Fighting Anti-Semitism, Genetically