Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

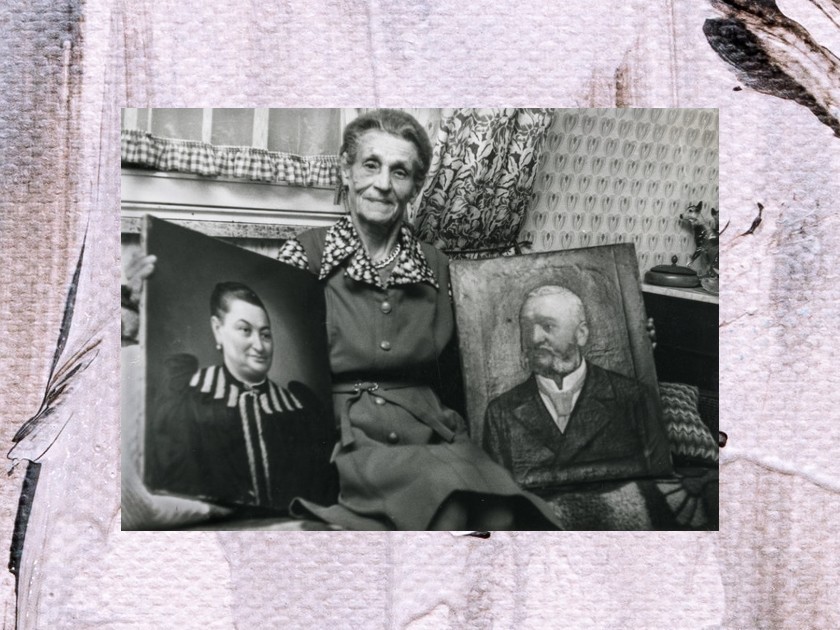

Emma Fischer, a former housekeeper in the author’s grandfather’s (Otto Kupfer) house in Weiden, Bavaria, holding the portraits of the author’s great grandparents Eduard and Fanni, which she had been safeguarding for forty years. Photo taken ca 1980. Image courtesy of the author.

The following is adapted from my recently published book, The Glassmaker’s Son: Looking for the World My Father Left Behind in Nazi Germany (Amsterdam Publishers, November 2022).

Much has been written about efforts to reclaim art looted from Jewish families during the Holocaust. Many of these stories involve valuable works by well-known artists such as Gustav Klimt and Camille Pissarro. But this is a Holocaust art story of a different stripe. The paintings in question have little commercial value, but to my family and me, they are priceless.

My father, who immigrated to the US in 1937, rarely spoke about his life in Germany before the war. In 1979, three years after he died, I decided the time had come to satisfy my curiosity about the world he had left behind. I wanted to see the house he had lived in, walk the streets he had walked, perhaps even meet some of the people he had known.

Shortly after visiting Dad’s hometown in Bavaria, I received a letter from an elderly woman named Emma Fischer, who had been a housekeeper in my grandfather’s house. Frau Fischer wrote that when my grandfather Otto and his sister Mina were forced to sell their house in 1939 under the Nazis’ Aryanization policy and move to Frankfurt, they asked her to safeguard a pair of oil paintings of their parents, Eduard and Fanni Kupfer, until they could return to reclaim them. Alas, Otto and Mina — along with six of their siblings and millions of other Jews — were deported and died in concentration camps (he in Theresienstadt, she in Treblinka), and never returned to Weiden, the small city near the Czech border where they had lived.

Fischer, who was ninety and nearly blind, did not learn about my visit to Weiden until after I had left. Had she known, she wrote, she would have invited me to stay in her apartment. “It would be a pleasure to give you these pictures in person,” she added. “I would like to speak to you personally because I have so much to say to you.”

Unfortunately, I wasn’t able to return to Weiden for four years. By then Fischer had died and the paintings had been inherited by a niece, a woman I’ll call Frau S. When I went to see her, S. demanded 30,000 DM, or about $12,000, a sum she claimed was based on an appraisal by a Munich art dealer.

I tried to reason with her, pointing out that my grandfather had entrusted the portraits to her aunt with the understanding that she would return them after the war. Moreover, Frau Fischer had clearly stated her intention to return the paintings to me. But S. insisted the paintings belonged to her and that she desperately needed the money. Besides, she added sharply, I came from a wealthy family and could well afford it.

It was hard to believe that nearly seventy years after my grandfather had been forced to give them up, Eduard’s and Fanni’s portraits would finally be reunited with their family.

While it was true that my father’s family had once been wealthy — the Kupfers had been important players in the Bavarian sheet glass industry for generations and at one time owned a dozen factories in the region — the Nazis had robbed them of most of their wealth and nearly wiped out the entire family.

But even if I had been the rich American she thought I was, I was not going to pay her even a pfennig. The paintings belonged to my family, after all, and had ended up in her hands only because of Nazi persecution. Besides, according to an independent appraisal, they were worth far less than she claimed, no more than $2,000 each.

After my visit, several community leaders, including the mayor, the head of the Catholic diocese, and the president of the local Lions Club appealed to Frau S. to return the paintings, but she adamantly refused.

As the years passed, I all but gave up hope of reclaiming the portraits. Then, in 2006, while visiting Munich, I decided to call Inge Roegner, a journalist in Weiden who had written several articles about my quest to uncover my family history. Our conversation soon turned to the subject of the portraits. “Peter, we must find out what happened to those paintings!” Inge exclaimed. She promised to investigate and get back to me.

Several weeks later, I received an email from Inge reporting that Frau S. had died many years earlier and that the paintings were now in the hands of her son, a man I’ll call Hubert. “Both paintings are hanging in his living room in Weiden!” Inge wrote. “Every day he and his family are admiring the pictures of Mr. and Mrs. Kupfer.

My cousin, Paul Sinclair — another great-grandson of Eduard and Fanni, who is fluent in German — wrote a letter to Hubert asking him to return the paintings. Two weeks later, Paul received a startling response from his wife, a woman I’ll call Audrey. Hubert had been killed in a motor scooter accident a few days earlier. But there was a silver lining to the tragic news. “With a very heavy heart,” Audrey wrote, she would return the paintings to the Kupfer family so that they would “again find a place where they belong.”

Franziska (Fanni) Kupfer and Eduard Kupfer portrait

The following year I met Paul and another cousin, David Mangel from Paris, in Weiden. As Inge drove us to Audrey’s house, chills darted up and down my spine. It was hard to believe that nearly seventy years after my grandfather had been forced to give them up, Eduard’s and Fanni’s portraits would finally be reunited with their family.

Audrey greeted us cordially and led us into her living room. Set in matching antique gold frames, the portraits were hanging above the sofa, commanding the attention of anyone who entered the room. Eduard, sporting a neatly trimmed gray beard, a dark velvet jacket with wide lapels, a high-collared white shirt, and a gold tie, looked every bit the captain of industry that he had been. Fanni, wearing a ruffled black dress trimmed with white embroidery, looked equally imposing.

Considering all they had been through, the paintings were in surprisingly good shape. Audrey explained that Hubert had had the paintings restored and placed in new frames. Save for a few cracks and blemishes, one would never have guessed that they had spent decades in hiding.

Audrey insisted that she hadn’t known who the subjects of the paintings were until she received Paul’s letter. But when we took the pictures down from the wall, we found some papers tucked behind one of them that told a different story. They were photocopies of articles about the Jewish community in Weiden, with passages about the Kupfers highlighted in yellow. So clearly Hubert had been aware of the provenance of the paintings, even if his wife had not.

We presented Audrey with five-by-seven reproductions of the paintings that Inge had made, along with a letter signed by Paul, David, and me thanking her and her family for caring for the paintings and agreeing to return them.

When we got back to the car, the three Kupfer cousins exchanged high-fives. “Wunderbar!” Inge exclaimed. “At last, the paintings are back where they belong.” Then we had a celebratory lunch and drank a champagne toast to Eduard and Fanni.

That evening, as I stood alone on the balcony of my hotel room, I thought about the long journey that had brought me back to Weiden. It took more than a quarter-century from the time I first heard about Eduard’s and Fanni’s portraits to get them back. Amid all the losses the Kupfers had suffered in the Holocaust, salvaging this piece of the family legacy felt like a small but important victory. And, of course, I thought about my father. I pictured him looking down on me and smiling, and I felt closer to him than I had in a long time.

Peter Kupfer is a freelance writer, editor, and photographer. His stories about business and technology, art and culture, travel, and other subjects have appeared in major newspapers and magazines, including the Washington Post, the Los Angeles Times, the New York Observer, and Metropolis magazine. He was a copyeditor at the San Francisco Chronicle for many years.