Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

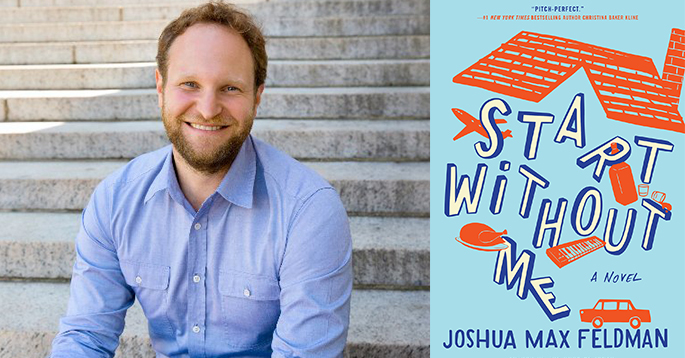

The following is from Joshua Max Feldman’s novel Start Without Me. The author of the critically acclaimed The Book of Jonah explores questions of love and choice, disappointment and hope in the lives of two strangers who meet by chance in this mesmerizing tale that unfolds over one Thanksgiving Day.

Adam looked up at the basement ceiling, not sure how long he’d been awake. There was no clock in the basement — never had been, for as long as he could remember. He pushed himself up on his elbows. Weak grey light filled the line of slender windows at the top of the wall. He’d been dreaming; something had woken him up. Then he heard the gurgle of a toilet flushing. A child appeared in the doorway in a corner across from the couch: a boy, five or six, in blue underpants and a Spider-Man T‑shirt, dark hair matted on one side, a sour, suspicious look on his face. “Who are you?” the boy demanded.

“I’m Adam,” Adam said. “Uncle Adam,” he clarified.

The boy shook his head solemnly. “My uncle’s Travis. He lives in Texas.”

“I’m your other uncle. Your dad’s brother.”

“Why are you on the couch?”

“Kristen’s — your cousins are sleeping in my room. My old room. What used to be my room.” The boy scowled, as though none of this added up, and Adam had to admit it didn’t sound very convincing.

“Uncle Adam,” he repeated. “You don’t remember me?”

The boy’s eyes narrowed. “Are you the uncle who smashed the piñata?”

“Jesus, that’s what you remember?” Did he actually owe apologies to the kids, too?

“The candy went all in the — ”

“It was a piñata, it was meant to get smashed. And if they didn’t want me to smash it, they shouldn’t have given me a turn.”

The boy made a slow movement of his thumb beneath his chin, which, in the mental squint of just waking, looked to Adam downright menacing, like a mafioso’s throat-slitting gesture. “Nobody’s allowed to download mods on my dad’s computer,” the boy intoned.

This nonsense alerted Adam to the absurdity of the conversation: The kid didn’t even know he was awake. “It’s okay, man, go back to sleep,” he said — would have preferred to use something more personal than “man,” but he wasn’t entirely, entirely sure whether this was Toby or Sam. Still, the child wordlessly obliged. He leaned his shoulder against the wall, padded back into the bedroom, leaving the door open — a gesture Adam found unreasonably touching, as though it were proof the boy didn’t hate him, didn’t fear him, after all.

He lay back down and stared up at the pocked tiles above him. The basement had a lurking, familiar odor: plaster and lavender air freshener locked in combat with something vaguely musty. He remembered what he’d been dreaming of: Music. Playing. Some sense of the sound still filled the corners of his memory: taut, sharp notes, like from a harpsichord, tripping down a thrumming baseline: a half song, half-remembered.

Once upon a time, he’d have made the effort to recall it, tried to reach into the cracks between sleep and waking to pull the chimerical sound out — sing it into a voicemail, the way you fixed a butterfly to a board with a pin. Occasionally, what he’d listen to an hour or so later wasn’t even half-bad. More often, though, what he heard was nonsense, and even before he stopped playing he’d concluded that it was a waste of time. He wasn’t actually dreaming of music — he was only dreaming of playing it: the texture and resistance of the keys under his fingertips, the beer residue in the metal mesh of the mic on his lips, the bass rumble from the stage through his torso, and more and more lately that rarest feeling, of getting picked up and carried by the music itself: no more distinction between him and the keyboard, between him and those he played with, between crowd and band, all of them racing along with the same roar — the communion of that, the freedom.

The paisley sheet his mother had made up the couch with had gotten tangled around his thighs in the night. He yanked it up toward his chin, but without much hope of getting back to sleep. The stillness of the house was deafening somehow — like all the sleeping people were vibrating at a frequency only he could hear: his family, ringing in his ears.

He kicked off the sheet and sat up, grabbed his jeans, crumpled on top of his duffel bag, and took out a sweatshirt. He climbed the carpeted stairs as he pushed his arms through the sleeves. Above the rail to his right were taped a dozen or more crayon drawings on white paper: houses and suns, oceans and triangle-sailed boats, violent inchoate swirls that resembled things he’d seen when he dropped acid in the Mall of America before a show in St. Paul. “The fridge just isn’t big enough when we all get together!” his mother had exclaimed as she’d led him down the night before — as though he were some kind of stranger, as though she were a tour guide, explaining to a foreigner what it was like when “they” were together. But he reminded himself: If he’d been absent for so long, he had only himself to blame. Fixed on the door at the top of the stairs was more kid art: brown, hand-shaped cutouts of different sizes, with glued-on elaborations (yellow feet, red-orange waddles, plastic googly eyes) to establish that these were turkeys. “Happy Thanksgiving!” one of his nieces or nephews had written in careful elementary school cursive on a piece of construction paper, masking taped above the doorknob. For some reason, it struck him like an ultimatum.

He opened the door a crack, listened: more tinnitus quiet, no one else was up. He moved as softly as he could down the corridor toward the front hall. When he was a teenager he’d snuck out so often, and apparently so needfully, he’d been able to make this trip without turning on a single light: the twelve stairs up from the basement, left and down this hall to the front door, his hand reaching the knob in the dark by pure muscle memory. Then he’d get into his father’s car, put it in neutral, and roll down to the end of the driveway, only then turning on the engine. And from there it was off to some friend’s or to some agreed-upon clearing in the woods, bottle caps and butts littering the ground like pine needles, or if there was nothing going on he and his friends would drive around the campus of the local state college, hoping to stumble on a party, smoking weed and listening to cassettes of Mudhoney, Guster, Pearl Jam, NWA. He knew he shouldn’t look back on those nights quite so fondly. But he couldn’t help it. Yes, it was drugs-and-alcohol- laden fun — but it was still fun.

He carefully opened the coat closet; the old ski jacket that his mother had pulled from somewhere was hanging next to the blue peacoat he’d worn from San Francisco. Within sixty seconds of his walking in, his mother had declared the peacoat “too nice” for the game of touch football planned for the following afternoon, and bustled around upstairs until she produced the ancient jacket. He’d tried to tell her he’d bought the peacoat for forty bucks at a thrift store almost a decade ago, and anyway, there was no reason to find an alternative at eleven o’clock at night. But she ignored him, and when she held out the ski jacket, of course he took it, of course he tried it on, and though the synthetic fabric was so stiff with age it was almost sharp, he declared that it was perfect, and thanked her, and thanked her some more. Why? Because he wanted to be agreeable — amenable, he thought as he took his cigarettes from the pocket of the peacoat, zipped up the ski jacket to his throat.

His pair of ratty Converse was on the drip tray amid a double line of neatly ordered Velcros and snow boots. He tied his laces and pulled open the door. And the instant the door parted from the jamb, the cat appeared out of nowhere and slid outside. “Fuck!” Adam said, making a flailing attempt to grab the animal by its tail as it darted out. He lost his balance and fell on his hip, knocking over the drip tray, one arm stuck outside.

He sat there for a moment, waiting for the whole house to wake up: doors flying open, shouts of alarm. As the quiet continued, he tried to assess what key of crisis, major or minor, this cat situation represented. Was it an outdoor cat or an indoor cat? Had it ever been to the house before? If so, was it allowed to roam the yard? It was Kristen’s family’s cat. Adam could imagine her twin daughters wailing when they heard; he imagined spending the whole day searching the neighborhood for the animal, only to discover its bloody corpse fresh from the maw of some displaced mountain lion or overzealous rottweiler or whatever. In short, the day ruined, and all his fault.

The open door was letting the cold air in; that had to be against the rules. He pulled himself up, went outside and shut the door behind him. With what the cigarette had cost him, he figured he might as well smoke it. And as he lit it and sat down on the top step, there was the cat — perched erect and expectant at his feet, swishing its tail, regarding him as though it were on to him, too: He didn’t know what he was doing. He didn’t know how to be an uncle or a son or a brother — not here, not anymore. Not without a drink. The cat sauntered up the steps; Adam opened the door and it vanished inside. “Asshole,” Adam muttered after it.

And then he smiled, because it was funny he’d called the cat an asshole. The whole thing was kind of funny, if you looked at it the right way: Uncle Adam, freaking out about the cat getting out, but the cat spent lots of time outside! It knew when to go out and come back in. Maybe proving he belonged wasn’t so much a matter of mastering every last rule for who slept where, when the cat was allowed to go out, what to do with the surplus crayon drawings, but rather knowing what it was okay to laugh about. “You’ll never believe what happened with me and that fucking cat!” he could tell them over breakfast. He took another pull on the cigarette, blew the smoke upward to try to warm the tip of his nose. The spruce trees at the end of the yard, planted by his parents when he was a kid to block the sight of Parr Street and the McReedys’ garage, were so still in the cold they appeared frozen solid. A bright layer of frost had settled over the grass of the lawn and over the slope of blacktop where the cars were parked:

Kristen and her husband Dan’s minivan; Jack and his wife Lizzy’s Tahoe; and last in line the cobalt blue Chevy Adam had rented in Hartford, because he hadn’t wanted anybody to have to come and get him from the airport. They’d offered, everybody’d offered; but again, he’d been trying to be amenable — so amenable they’d hardly notice he was there.

He smacked his fingers against his palms, finally fixed the cigarette at the corner of his mouth and stuck his hands under his armpits. Smoking without your hands was one of the easier things you could learn to do at a piano. He should’ve found a pair of gloves in the closet, though. Even when they weren’t squeezed in his armpits on a freezing New England November morning, the joints of his fingers ached when he first woke up. He’d met an older jazz guy in Miami who’d had to stop playing altogether because of the arthritis. All things considered, though, you had to have a pretty lucky career for arthritis to force you out, and not the mile-below-the-poverty-line money, or the burnout from the road, or the booze and the bars, not to mention all the harder stuff you could get with as little as a mutter to the right promoter, hanger-on, somebody-on-the-bill’s girlfriend. He remembered at a party after a Kiss and Kill show in New Orleans, in some sweltering shotgun crash-house, he’d wandered into a back room and stumbled on a shirtless, comically mulleted guy poking at the thighs of a glassy-eyed redhead, her jeans around her ankles. It took Adam a moment to register the syringe clasped between the dude’s teeth. He looked up at Adam and grinned around the syringe like the fucking Cheshire cat.

“What about you, amigo?” he asked, taking the syringe from his mouth. “You’re in the band, you want one on the house?”

Earlier in the night, he’d introduced himself as a friend of Johanna’s. And maybe he was. You could never guess who her friends would be — where they came from, what they wanted. Adam couldn’t say whether he’d been too smart, or too scared, or simply plain lucky to have refused that offer — that and the thousand others like it, escaped all those choices even worse than the ones he’d made to make it back here: the steps of his parents’ house, on Thanksgiving morning. The juxtaposition of the two moments — heroin in the back room, the sleepy home on Thanksgiving day — somehow made both of them seem ridiculous, maybe made him seem ridiculous, too, with the clumsily stitched-together persona he’d carried on with for so many years: the rock keyboardist, the nice suburban kid from western Massachusetts.

But what did he care if he’d turned out to be ridiculous? He ought to be thrilled to be nothing worse than ridiculous! And he wished he could explain something like that to Jack, or to his dad, or to any of them — that he was grateful, grateful almost to tears, to be here: sober for nine months and four days (as of this morning), invited back for a family holiday. From the moment they closed the door behind him, though, it’d been awkward. His mother giggled painfully after she asked him if he wanted anything to drink. His father kept announcing how glad he was to see Adam while clasping his hands together and shaking them in front of his chest, like a politician pleading for racial harmony. The only other person who’d waited up was Jack, and Adam couldn’t help wondering whether his older brother had stayed up on the chance Adam would show up blotto, and they’d need to throw him out. When Adam said after five minutes he was exhausted and just wanted to get some sleep, he could tell they were all relieved.

He put the cigarette out on the bottom of his shoe, slid the butt into the pocket of his jeans. As he opened the door, he saw above it was hammered a strip of sanded wood with the words “The Warshaws” painted in blocky purple letters. The loneliness he felt looking at that sign was at once so predictable and so unaccountable all he could do was stand there. Then he went back inside.

He took off his sneakers, righted the drip tray and the scattered shoes, hung up the ski jacket, and went into the kitchen. The table was already set up as the children’s table: orange paper tablecloth, paper plates with cartoon Pilgrims, the centerpiece a fan-tailed, leering paper turkey. He surveyed the family photos on the shelves above the sink, images spanning from his and his siblings’ childhoods to the birth of Kristen’s twins. There were a few photos of him playing: a recital when he was six, looking freakishly tiny at the keys of a six-foot grand; the time Kiss and Kill played Late Night in the Conan era. (His mother must have cut the photo to leave Johanna out; pretty tactful, he had to admit.) The most recent photo of him was maybe five years old, some solo show he’d done: his back bent, his face down near the keys, eyes shut, lips curled in concentration — the Artist at Work, or trying to look that way. He’d lost weight since then — his face at thirty-five narrower, the angles of chin and cheek sharper. He had an impulse to hide his pictures behind the others, but his mother being his mother would notice, and he’d have to explain what he’d done. Why should he feel humiliated? she’d want to know. She had the pictures out because they were proud of him (which, of course, was the most humiliating part of all).

He dropped the cigarette butt into the trash can under the sink, and shook the can so the butt jiggled under a banana peel. He pulled opened the refrigerator, looking for he wasn’t sure what. The shelves were stacked with casseroles and tin-foil-covered pots, ready to be reheated. A couple green glass bottles sat wedged in the door: sparkling cider, he saw from the labels. He had a hunch they’d even gotten rid of the cough syrup.

He imagined making himself useful — tidying up, putting away. But everything was spotless: the countertops wiped down, the cereal boxes on top of the fridge lined in descending order. A piece of yellow legal paper was taped to the handle of the dishwasher, on which one of the kids had written “Clean!” Adam lifted the paper. On the back was “Dirty!” with some comically grubby plates and glasses, flies buzzing around them in the air. He smiled again. He loved these kids.

He didn’t know which one had made the sign, so he felt his love for all of them collectively — felt it as a form of relief. He switched the sign over to “Dirty!” and opened the dishwasher. But as he took out the first pair of clean plates, he realized he didn’t know where anything went. There was a coffee pot in the top rack; the coffee maker was plugged in on the counter. Okay, this he could do. He could make them coffee. He could fill the house with the smell of freshly brewed coffee in the morning. Who could object to that?

He took the glass coffee pot from the dishwasher and set it on the counter by the coffee maker, took out the plastic lid and the filter basket. He opened some cupboards, got lucky and found the filters. The coffee was right there in the freezer, like he’d guessed. So far, so good. He slid the filter in the basket, spooned in the coffee grounds, snapped the basket into the coffee maker, and poured in the water. He even imagined himself doing it all with a certain finesse — the practiced grace of his hands. And maybe this idea made him careless, or maybe it was something else, but as he tried to snap the pegs of the lid into the holes of the pot, the pot slipped from his hands. It made a balletic turn on the counter and spun off the edge.

He didn’t even bother to watch whether it broke, only listened, with hope that bordered on prayer. Silence followed the shattering sound. Then he heard from somewhere in the house, “Dad!” And then the same voice, more desperately, “Moooom!” And he heard doors opening. He knew he ought to pick up the larger pieces of glass, find a broom and a dust pan, be there to warn anyone who appeared about the shards and apologize for depriving them all of coffee on a holiday morning. He ought to do a thousand things that real members of a family would do without thinking. But he found he lacked the will to do any of them. He went back to the closet, put on his peacoat, and went outside. Sunlight was slanting through the needles of the spruce trees. Maybe he should go out and get coffee — that would make up for all of it. “Don’t worry, Uncle Adam got coffee from town!” Someone would clean up the glass; surely, no barefooted child would step on the pile of glass, need stitches — shit, for all he knew, lose the foot.

This was called catastrophic thinking, he’d been taught at Stone Manor, the Maine rehab he’d been through at the beginning of the year: His mind had a compulsion to seek out the worst possible outcomes. Why did it do that? Harder to say. But the point was, he shouldn’t trust his fear that breaking the coffee pot would lead to one his nephews losing a foot. He could have another cigarette, and in a minute he’d go back inside and clean up the glass — and explain.

But that was the part he couldn’t summon the energy for: the explanations. Having to say, over and over and over — to Jack and his mother and father and Kristen and Dan and Lizzy and Emma and Carrie and Toby and Sam and the baby whose name he forgot, and hell, to the cat while he was at it — tell them all about his meager hopes of making them coffee, and how with his graceful hands, he’d fucked it up.

No, he couldn’t do it. Not after one cigarette, not after a hundred. Not sober. He dug in the pockets of his peacoat and found the keys to his rental car. He walked across the lawn and got in, put the car in neutral, rolled down the drive, stopped at the bottom of the hill, and started the engine.

From Start Without Me. Used with permission of HarperCollins Publishers. Copyright © 2017 by Joshua Max Feldman.