In 1980, the British philosopher Michael Dummett authored the essential scholarly book on the history of the Tarot: the perpetually out-of-print The Game of Tarot: From Ferrara to Salt Lake City. Dummett’s primary thesis, presented with an encyclopedic array of evidence, is that Tarot cards were used exclusively for game playing and gambling for centuries before anyone ever thought to use them for fortune telling. His secondary thesis, expressed with a surprising degree of venom, was that the writers of the occult Tarot — Eliphas Lévi, Aleister Crowley, and others — were charlatans and frauds.

A review of The Game of Tarot by historian France Yates published in The New York Review of Books (February 19, 1981) disputed Dummett’s blanket rejection of the possibility that the early Tarot could have served as a vessel for secret knowledge. The correspondence of the twenty-two major arcana with the twenty-two Hebrew letters, she wrote, “introduces the possibility of a Cabalist interpretation.” Furthermore, she offered that on La Papesse, the female Pope card that eventually became the High Priestess, the curtain behind the figure’s head could possibly be a Torah scroll “now unrolled or unveiled in Cabalist interpretation.” Appreciate that Yates felt the need to repeat the words “Cabalist interpretation,” lest the reader err in wandering off in a different interpretive direction with Hebrew letters and a secret Torah scroll.

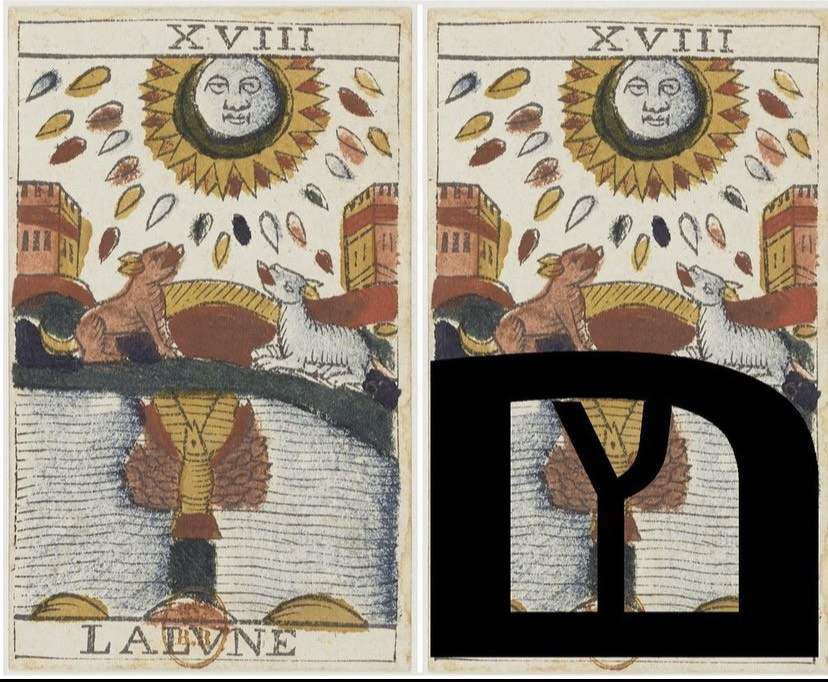

La Lune (The Moon) contains a secret depiction of Passover. In the card’s body of water and lobster are concealed the Hebrew letters mem sofit ם and tzadik sofit ץ. Mem and tzadik are the first two letters in the Hebrew words for Egypt — Mitzrayim מצרים and matzah מצה.

My new publication, The Torah in the Tarot, comes out from Ayin Press in October of this year. In it I argue that both Dummett and Yates — the Tarot historian and Tarot esotericist alike— failed to discern the Tarot’s foundational secret. Furthermore, I demonstrate that when we use a Judaic interpretative lens, one specific historical deck, the Jean Noblet of 1650 Paris, reveals itself to be an ingeniously designed secret vessel for Hebrew letters, Torah stories, Judaic ritual objects, and Jewish holy days, a realization that entirely upends our current understanding of Tarot history. And, most importantly, I show that the Jean Noblet Tarot is a singular masterpiece of Jewish resilience that deserves to be widely known and deeply studied.

For years, I have corresponded with Tarot scholars — ranging from amateur enthusiasts to accomplished authors — about the possibility of a significant Jewish contribution to the evolution of the Tarot, based on recognizable Jewish symbols in the Noblet and other historical decks. Not everyone has agreed with my thesis; the most frequent counter argument offered is that Judaism was too obscure — and by implication, too foreign — to possibly have played any role in the Tarot’s development. Another objection that I often hear is that the Jews of Europe had no need for a secret tool for preserving the language, holy days, and rituals of Judaism. Overall, my interaction with the Tarot community has been an education on how challenging it is for the non-Jewish world to incorporate Judaism into their narratives of history and how faintly the world remembers the centuries of antisemitism that preceded the Holocaust.

Karl Marx observed that history repeats itself, once as tragedy and a second time as farce. True to Marx’s words, we find in the Tarot an instance of history repeating as farce. Just as many Christians are shocked to learn that Jesus was Jewish, the occult community struggles to acknowledge that many of its venerated symbols, such as the Tree of Life, were originally Jewish. Just as the Church of the Middle Ages purged Judaism from the Old Testament, Eliphas Lévi purged Judaism from his syncretic Cabala. And just as the Church enshrined Latin as the sacred language of the Torah, so Arthur Waite — the designer of the famous Rider-Waite-Smith Tarot of 1909 — apparently, knowingly repurposed the Tarot’s Judaica for his own spiritual project.

Thankfully the Catholic Church of 2025 is not the Catholic Church of the Middle Ages. Catholicism evolved and found ways to reconcile the theological worlds of Judaism and Catholicism. And, so, I hope for history to repeat itself once again for the Tarot community; perhaps not as farce, but in miniature. I hope that Tarot theorists, historians, and enthusiasts can open themselves to the possibility of a unique Jewish contribution to the symbolic world of the Tarot, and that they greet this new realization not as a narrowing of the Tarot’s horizons, but rather as a dramatic expansion of its spiritual depth.

For the Jewish community, The Torah in the Tarot presents a different challenge. The wise cynics among us will understandably suspect that this story is too fantastical to possibly be true; others will find it challenging to see beyond the Tarot’s firm cultural anchoring as a device for fortune-telling. But if we can set our skepticism aside for a moment and approach the Noblet Tarot with entirely fresh eyes, I suspect we will be collectively astounded and enchanted by what has been quietly hiding in the cards for nearly four hundred years.

Stav Appel is a data scientist and a lifelong student of Torah. Earlier in his career he was the director of the Israeli-Palestinian coexistence organization Nitzanei Shalom, and the director of International Service Programs for American Jewish World Service. He holds an MBA from the Yale School of Management and has studied Biblical Hebrew at Hebrew University and Yale Divinity School.

After a chance encounter with an old deck of Tarot cards, Stav began to explore the origins and meaning of the biblical references he recognized in its images. He is now a frequent speaker and popular writer on the Torah in the Tarot, the lost and forgotten Judaic origins of the mysterious Tarot de Marseille. He currently resides in North Salem, NY. Find Stav on Instagram @torah.tarot.