Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

Photo by Lokesh B Masania on Unsplash

One afternoon in 1979, during the spring of my senior year at Vassar College, someone came knocking on the door of my dorm room, I opened it to find a woman in her late 30’s or early 40’s who said she had lived in the room during her senior year at Vassar, could she come in and look around? I said yes and once she was inside, I noted how she took in the posters I had tacked on the walls, the battered velvet armchair I’d bought at the local Salvation Army for ten dollars, and the books on the shelf. I could see the experience was important and meaningful for her and she thanked me for allowing her to have it.

When the door closed behind, I was left to go back to whatever I had been doing before. She seemed nice and I was glad to offer her the opportunity she’d sought. But I was puzzled too, though I had come to love Vassar and was happy there, I was also impatient to graduate, and for my real life, one that would, I hoped, include graduate school, jobs, apartments, boyfriends — some of the milestones of adult life — to begin. I couldn’t imagine coming back to this room in twenty years and asking if I could look around; by then, college would be the distant past and I imagined being firmly rooted in whatever I had been able to create. I couldn’t have known just how wrong I was — Vassar, and my time there, would not remain in the past; Vassar is very much with me still and, in some sense, created the person I am now.

I grew up in a middle class neighborhood in Brooklyn, NY. Our neighbors and friends were Jewish, as were most of my classmates. This being New York, there were, of course, other religious groups who lived nearby; they were mostly Catholic, either Irish or Italian. Those kids went to the Immaculate Heart of Mary, a nearby parochial school. There was no animosity between the groups but there was little interaction either. We stuck to our own.

There were plenty of Jewish students around me. Jewish faculty members too. But there was also a privileged class I had not encountered before, and certainly not in any significant numbers.

Fast forward to 1974, when I entered Vassar as a freshman. There were plenty of Jewish students around me. Jewish faculty members too. But there was also a privileged class I had not encountered before, and certainly not in any significant numbers. These were the WASPs and Vassar was teeming with them. This group was foreign to me, and in their own way, exotic to me. The Muffys and the Taffys, the Chips and the Skips (Vassar had been coed for a few years by this time). I felt intimidated, envious, and disdainful all in a swirling, not entirely comfortable mix. And while I didn’t experience much overt antisemitism (my freshman-year roommate informed me that my people had killed Christ, while another student complained about how Jews never stopped talking about the Holocaust) these instances were occasional and not especially wounding. What was more corrosive was the gradual awareness that Vassar had been founded, in part, on excluding people like me. Jewish girls had not gone there in the nineteenth-century and attended only in capped numbers well into the twentieth. Once I knew this, it wasn’t something I could unknow and as much as I loved the institution and felt proud to be a part of it, I had to accept my historic exclusion, and it forever colored my experience.

This intersection of Jewish/non-Jewish life at Vassar shaped the way I saw the world and how I found my place in it. The Jews’historical refusal to become Christian, our Bartleby-like stance, off to the side, saying no, we’d prefer not to, had come to define us. Being at Vassar made that abundantly clear.

So being a writer, I started writing about it. In 2018, HarperCollins published my novel, Not Our Kind, which was about the unlikely relationship between a young Jewish woman who grew up on Second Avenue and the Park Avenue matron who becomes her employer. I set the book in the late 1940’s because that was a time when these lines were even more sharply drawn — the word restricted was used widely and without shame to let people know that if they didn’t like Jews — or Blacks — they need not have worried as the hotel/resort/town did not admit them.

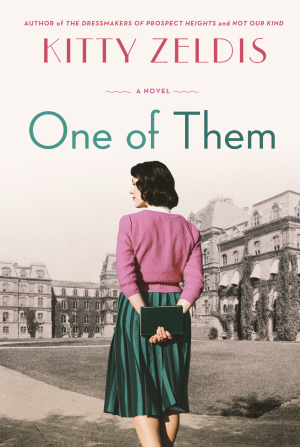

That novel allowed me to examine and explore these issues and now, with my new novel, One of Them, I’ve returned to the subject. The time period is the same, but this novel is set at Vassar and is about two girls who live their Jewishness differently. Despite appearances to the contrary, Anne Bishop decides not to tell anyone at Vassar that she’s Jewish, or that her father changed the family’s name to pave his way in the world. Delia Goldhush has no such refuge, and she’s subject to the scorn and malice of her classmates. The choices these two girls make, how they deal with their backgrounds and identities, let me tease out the issues. I’ll always be interested in the subject of identity and exclusion and I hope, by telling Anne and Delia’s story in the most specific, relatable way I know how, that both Jews and non-Jews will share that interest with me.

One of Them by Kitty Zeldis

Born in Chadera, Israel, Kitty Zeldis is the pseudonym for an award-winning author of eight novels and over thirty-five books for children. Her essays, articles and short fiction have been published in many national and literary publications. She is also the Fiction Editor of Lilith Magazine. Zeldis lives in Brooklyn, NY.