Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

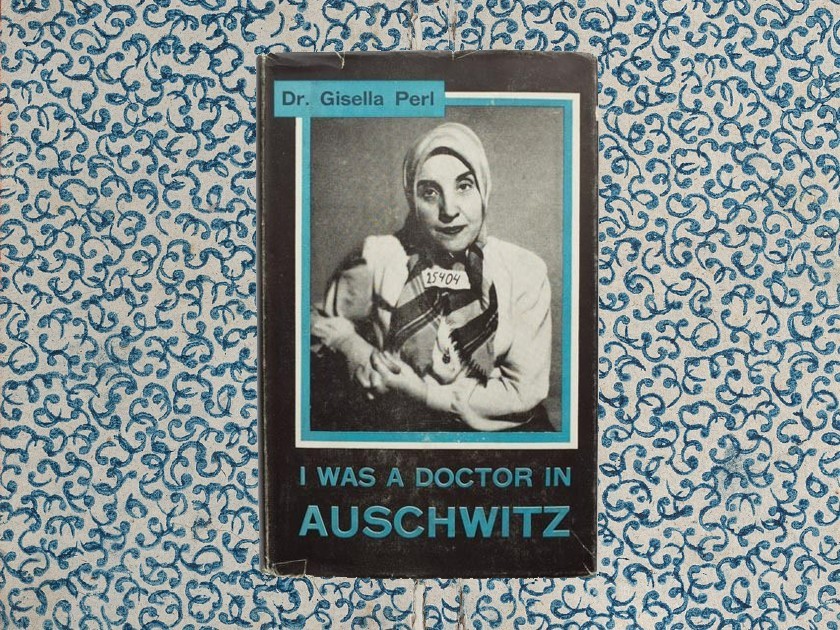

Book cover with blue curved line pattern

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1940

Gisella Perl was an extraordinary woman. She was a trailblazing physician and infertility researcher; a wife, a mother, a Jew, and a prisoner of the Nazis in the 1940s. Her memoir, I Was a Doctor in Auschwitz, was first published in 1948 (and re-released by Lexington Press in 2019) and offers a heartbreaking but important record of life in the death camps.

Written shortly after liberation, Perl’s memoir contains familiar elements found in so many personal narratives of the Holocaust. For instance, like millions of other families, Perl’s was separated immediately upon arrival at Auschwitz; she would never see her parents, husband, or young son again. Her abilities as a physician saved her from the gas chambers, but the physical and emotional despair she chronicles make it clear that life in a concentration camp was a hellish purgatory where one waited for death.

Perl’s time in Auschwitz (and later Bergen Belsen) offered her unique opportunities to help others. She and eight other women were forced to run a medical clinic where they were expected to care for fellow inmates without any medical supplies. They were overseen by Josef Mengele, the sadistic “Angel of Death,” as he was called, who performed cruel experiments on prisoners before killing them. Though this role was forced on her, Perl used it to do as much good as possible, such as sneaking out of her bunk at night to perform abortions, since pregnancy was punishable by death at Auschwitz.

In her influential book People Love Dead Jews: Reports from a Haunted Present, Dara Horn argues that Holocaust narratives only achieve wide readership if they downplay the pointlessness of the terror the Nazis inflicted on Jews and “teach us something beautiful about our shared and universal humanity, replete with epiphanies and moments of grace.” For example, The Diary of Anne Frank is an international best-seller, according to Horn, because it doesn’t contain any descriptions of the death camp’s atrocities. Readers glom on to phrases such as “I still believe, in spite of everything, that people are truly good at heart.” “These words are ‘inspiring,’” according to Horn, “by which we mean they flatter us. They make us feel forgiven for those lapses in our civilization that allow for piles of murdered girls.”

I Was a Doctor in Auschwitz forces readers to confront the suffering head-on through Perl’s detailed discussion of the women she knew in the death camps.

This is not a misrepresentation of the Holocaust by Anne Frank, but rather a misappropriation of it by post-war Western culture, where (mostly non-Jewish) organizations like publishing houses and educational institutions elevate some Holocaust narratives over others. Horn’s point is that most of the favored literature has been selected because it allows readers to feel good about themselves when reading it. These texts contain a veil between the reader and the worst truths of the Holocaust, often focusing on survivors rather than those that died, the good that was found amidst suffering, or even obscuring potential parallels between readers and the bystanders who allowed the murder of six million Jews. (The fact that John Boyne’s 2006 The Boy in the Striped Pajamas—long derided for its inaccurate portrayal of Auschwitz and sympathetic portrayal of Nazi characters — is getting a sequel seems to further prove this point.)

In light of Horn’s hypothesis, it is obvious why most people have never heard of I Was a Doctor in Auschwitz. Perl’s memoir breaks almost all the rules of polite Holocaust literature. While there are a few high points, such as the emotional connections she forged with fellow prisoners and the determination she felt in her mission to help the women in the camp, these moments are punctured by detailed descriptions of the hellscape in which they occurred.

For example, most of the friends Perl made were murdered, even those whose will to live seemed unbreakable. One woman, Ibi, wanted so desperately to live and find her son that she jumped off the truck taking her to the gas chambers six times. Despite Ibi’s determination and bravery — and Perl’s attempts to hide her friend from Nazi guards — she was eventually hunted down and murdered. Another friend, Lily, was convinced she would live to see liberation. “I want to live. I want so much to live!” she told Perl, “I have such faith that these barbed wires will fall, that these gates will open, that we will once more be free.” However, her attempts to avoid the gas chamber were also ultimately futile. Perl pulls back the veil between the reader and these women, forcing us to understand that the death camps were full of people who desperately wanted the lives that were stolen from them.

It’s as if Perl knew in 1948 that the collective memory of history would do its best to erase the existence of women like Lily and Ibi. That their stories would be too disturbing and upsetting, so they would simply be forgotten. Despite the number of times #neverforget is retweeted on Holocaust Remembrance Day, Yom HaShoah, people are forgetting about this genocide. Holocaust curriculum and books are disappearing from schools at an astonishing rate. According to one recent survey by the Claims Conference (a non-profit that works to compensate Holocaust survivors and fight antisemitism), over ten percent of Americans under the age of forty had never heard the word “holocaust,” and 63% did not know that six million Jews were murdered (an alarming percentage even believed that Jews caused the Holocaust).

This points to the importance of stories like Perl’s that do not shy away from bearing witness to the horrors Nazis inflicted on millions of individuals who deserve to be remembered truthfully. “Whenever I see the word ‘Six Million Dead’ or ‘Six Million Jewish Victims” printed in a newspaper,” Perl writes:

“My hands harden into fists and my heart beats stronger with revolt. Those six million dead are so many terrible, heartbreaking stories; they are Bettys and Roses and Annes, they are Julikas and Charlotte Jungers, each and every one of them represents not only the second of death, however horrible that is, but an entire, colorful, exciting, human life, past, and what is more, a future…”.

The ellipse makes readers acknowledge that the women and children of whom she writes had those futures stolen in the worst way imaginable. I Was a Doctor in Auschwitz forces readers to confront the suffering head-on through Perl’s detailed discussion of the women she knew in the death camps. Their stories matter because their individual lives — their hopes, dreams, sorrows, and pain — mattered.