Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

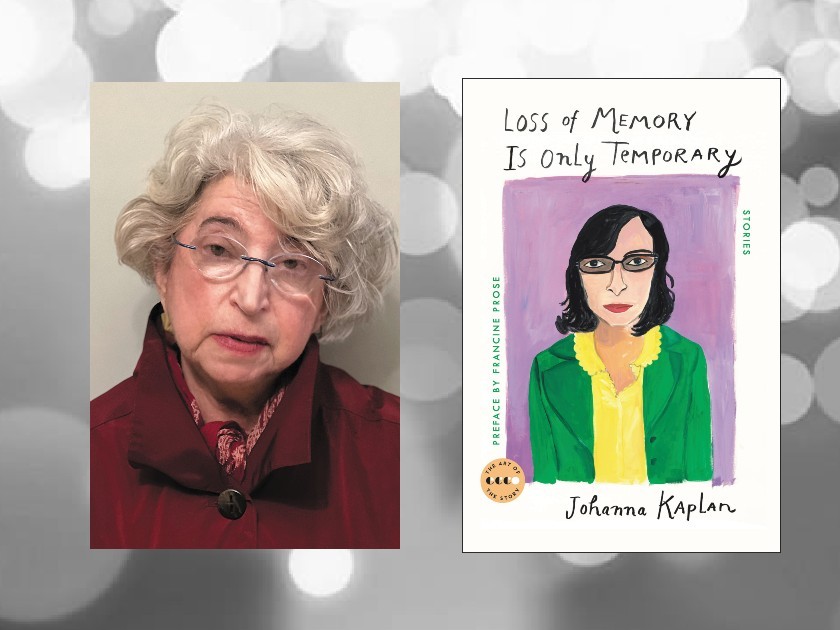

Author photo courtesy of the author

Francine Klagsbrun spoke with Johanna Kaplan about her latest book, Loss of Memory Is Only Temporary: Stories.

Francine Klagsbrun: Your stories are beautifully original; each seems to open up a universe of its own. What led you to fiction writing? Were there writers in your family before you? Did you start writing as a child and did your family encourage you?

Johanna Kaplan: I come from a story-telling family. Both my parents were unstinting in talking about their own lives, and the lives of their quite different families – their childhoods, their early work lives, and in my father’s stories, his Lower East Side childhood neighborhood. His accounts were filled with unique, wry humor and a near ventriloquism, his innate gift. My mother was a very different kind of narrator, intensely impassioned. She filled her stories with the intimate details of the troubles and triumphs of shtetl life from her own youth, and frequently included accounts of Europe’s Jewish past. Though I was a great reader as a child, I kept my wish to become a writer mostly to myself, since my Depression-battered parents did not encourage it.

FK: The characters in your short stories are very different from on another. Yet there is a sense of irony and humor that marks many of them. When writing a story do you begin with a character you want to create and let that being shape your narrative, or do you have a storyline in mind and fit your characters into it?

JK: Almost all my stories are begun with a phrase or a sentence I “hear” in my mind’s ear. Then I have to find out who that person is, to whom he or she is speaking, and what those lives are all about. From there, the story evolves. Sometimes I know from the start what a character is wearing, even if I don’t yet “see” the whole person clearly. I’ve found inspiration from other sources as well: a newspaper article, an obituary, the face of a person I’d see on the bus or in a store.

FK: Anyone who has read your work immediately notices your uncanny ability to convey perfectly the voice of your characters, whether the German-born Maria, in “Other People’s Lives,” or the Israeli playwright, Amnon, in “Sour or Suntanned…”. Is that “perfect pitch” in writing related in any way to the beautiful singing voice I happen to know you have? Or is it a desire and ability to really listen to people when they speak?

JK: I don’t have literal perfect pitch, but for singing and for listening to music my sense of pitch is wincingly accurate. Luckily, that same quality obtains for nearly anyone’s speaking voice, though for an unfamiliar accent, I do have to hear it many times to set it in my ear. The connection between music and creating dialogue? A good ear is the basis for both.

I think my stories resonate today because the pathways to the heart and mind are universal and unchanging, as is the hunger for stories.

FK: Several of your characters have psychiatric connections, such as Louise, the former mental patient, in “Other People’s Lives,” and Naomi, the young psychiatrist in the title story, “Loss of Memory…” In your own life, you taught children hospitalized for psychiatric illness. Was this always an area of interest to you? How did that interest influence your writing in general?

JK: My mother was a psychiatric social worker who missed her earlier professional life so much that she often talked about it when she was at home before she did go back to work. My father, a teacher, often brought home colleagues with “problems,” and my mother would close the kitchen door as she practiced her profession without charge. I had done some tutoring of children hospitalized for psychiatric illness in college, so that when it was time for me to earn a living, teaching these children seemed an easy choice. Much of my work reflects the distinct ambience and understanding I gleaned in my unusual teaching years since my classroom and students were located in the Child Psychiatry department of a major hospital.

FK: Your stories center on Jewish characters and frequently Jewish New York. Yet they resonate universally. Do you think Jewish writers have a special responsibility in the way they handle their subject matter?

JK: The majority of my stories, and my novel, O My America! center around NYC Jewish characters, both immigrants and American born, and all my stories reach across several generations. Yet, as a lifelong New Yorker, the vibrant, hectic voices of that great multitude of city-dwellers are always within my listening ear. I think my stories resonate today because the pathways to the heart and mind are universal and unchanging, as is the hunger for stories. Still, for me, as a Jewish writer, early imbued with the concept that all Jews are responsible for one another (Kol Yisrael arevim zeh la zeh), when I consider the recent shocking rise of antisemitism in our own “Golden Diaspora”, and am writing about Jews whose behavior is reprehensible, doesn’t some measure of ambivalence, if not conflict arise?

FK: How much Jewish education did you have – Hebrew school, Jewish camps? Do you speak Yiddish as well as Hebrew, or read Yiddish literature?

JK: My early Jewish education was limited to after-school Hebrew School, but Rabbi Israel Miller’s Hebrew School at the Kingsbridge Heights Jewish Canter was so superb that it came to be deemed a model. I did always go to Jewish camps, first Kindervelt, and then to Camp Habonim, the Labor Zionist Youth Movement’s summertime attempt at replicating kibbutz life, then in its heyday. It’s to Habonim’s year-round activities that I credit my mid-level conversational Hebrew, and a heightened overall Jewish/Hebrew/Israel education. As for the childhood Yiddish I once knew, it had long disappeared into mere partial understanding. Still, recently, I’ve found to my amazement, that solely at unsuspecting moments, a vagrant phrase or an entire Yiddish sentence will jump into my head and onto my stunned lips; that striking reveal means I know more Yiddish than I’ve realized. A result of the Pandemic’s isolation, perhaps?

FK: Readers often confuse fictional writing with a writer’s real life. In what way, if any, do you draw on your own biography in your writing? Did you really have a great-aunt who became a doctor and knew Isaac Babel, as in your story, “Family Obligations”?

JK: I did have a great-aunt who’d had to serve as a doctor on a Red Army train going to the battlefields of Eastern Europe in the 1919 – 20 civil war, but she was not on the same train as Isaac Babel, nor did she know him. But since Babel did travel on a similar train to the Front as a war correspondent (Red Cavalry), I put the two of them together on the same train, and had him write a fictional report – my imagined account of my great-aunt’s life in that period. Still, even sophisticated readers can confuse a story that appears to be autobiographical with the writer’s real life; in my stories, when there is an autobiographical kernel I’m aware of, it has always been greatly transformed. So fiction readers should keep in mind that a narrating voice is just that: the voice a writer has chosen to tell a particular story.

FK: Can you tell us something about what you are working on now?

JK: I’m working on a short story with an autobiographical root that then goes far afield (“Almost 1950”), and a novel, temporarily titled “Forbidden.” I’d put that book aside for a while because some of its characters, members of a very wealthy, very high-achieving Jewish family behaved in such shocking ways that it made me uncomfortable. But they kept talking to me anyway, so I have had to go back.

Francine Klagsbrun is the author of numerous books, most recently Henrietta Szold: Hadassah and the Zionist Dream, part of the Jewish Lives series published by Yale University Press. Her previous book, Lioness: Gold Meir and the Nation of Israel, was named the Everett Family Foundation Book of the Year for the 2017 National Jewish Book Awards. She was the editor of the best-selling book Free To Be…You and Me and wrote opinion columns for many years in both the Jewish Week and Moment magazine. Her writings have also appeared in such national publications as The New York Times, Boston Globe, Newsweek, and Ms.