Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

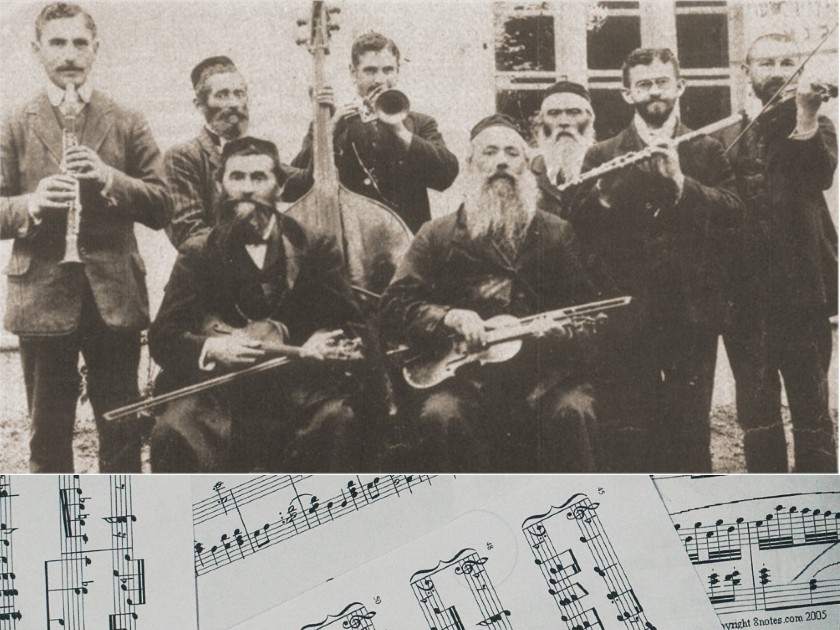

Jewish family of musicians from Rohatyn, modern-day western Ukraine, most of them members of the Faust family, 1912; edited by Simona Zaretsky

Tina Frühauf’s book, Experiencing Jewish Music in America: A Listener’s Companion, follows the question of what Jewish music can, should, and ought to be, by providing snapshots of an extensive range of musical genres and styles that have been central to the Jewish experience on US soil, beginning with the arrival of the first Jewish immigrants in the sixteenth century and the chanting of the Torah, to the sounds of pop today.

Imagine you are visiting a record store, actual or virtual, looking for “Jewish music in America.” What would you find? In the same rack there might be cantorial classics sung by Yossele Rosenblatt and klezmer music; you might find Israeli folk music, and songs in Yiddish and Ladino; you might see one of the CDs by Hasidic pop star Lipa Schmeltzer or stumble over John Zorn’s experimental sounds; you will certainly find an abundance of classical music by composers of Jewish heritage. The inventory of a record store is as much a microcosm of Jewish music, as the United States is a microcosm for the Jewish cultures of the world, from the Bukharian Jews in Queens, to the Syrian Jews in Miami, and the Persian Jews in Los Angeles. This diversity began in the eighteenth century. Earlier, Jews in the New World were largely Sephardim; the Ashkenazim arrived thereafter, followed and then paralleled by Jews from North Africa and the Middle East. In the twentieth century, other groups such as Yemenites and Ethiopian Jews settled in the United States as well. Within these groups some are religious to various degrees and some are secular. Diversity is inherent in Jewish culture, musically and otherwise.

Given this diversity, how does one understand the category of Jewish music? Like many terms, “Jewish music” is a construct, a concept that emerged in later modernity. In the United States, it first appeared in print in Sam L. Jacobson’s (1873 – 1937) essay, “The Music of the Jews” of 1898, published in the monthly magazine Music. Since then, attempts to define Jewish music have faced many difficulties and have stirred up controversies.

Like many terms, “Jewish music” is a construct, a concept that emerged in later modernity.

In the early twentieth century, Abraham Zvi Idelsohn, an ethnologist, musicologist, and composer born in Latvia, perpetuated the idea of the underlying cultural unity of the Jewish people throughout and in spite of their geographic dispersion over centuries. He put forth the notion that the music of the various Jewish communities conveys the linearity of a history dating back to ancient Jerusalem. This view has been contested based on the evolving heterogeneity of the Jewish people in various Diasporas. More so, many Jews did not merely continue existing traditions; rather, they created new ones — a process difficult to accept by some communities, where preservation, not creation, is the defining norm. Music, used in sacred and leisure contexts, has played a key role in ideological debates about tradition and innovation.

Considerations on the meaning of Jewish music took a new turn when the modern State of Israel was founded in 1948. Curt Sachs’s famous definition in 1957, “music by Jews, for Jews, as Jews,” celebrated for its poignancy and widely applied, has also received much criticism. It begs an answer to the overarching question of who is a Jew, and an answer that depends on who you are asking. For some, Jewishness is in the genes, transmitted based on matrilineal succession since the time of Ezra; for others, Jewish identity is constructed by society, whether by members of the group or outsiders. Indeed, what does it mean to be Jewish in the modern world? Capturing Jewishness broadly, it can be understood as a racial, cultural, ethnic, or religious category. The dilemma of Jewish music comes down to what is considered Jewish and by whom.

The answer then, to what “Jewish music” is, all depends on who defines it, when, and under what circumstances. Some insist on a Jewish ritual context and traditional languages — Hebrew, Yiddish, Ladino — or melodies; others see the Jewish heritage of the musicians as sufficient even when non-Jewish musical influences are dominant, and still others embrace music by non-Jewish musicians based on Jewish themes. The term also carries expectations of “authenticity” or rather, originality, sometimes leading to heated debates in the evaluation of musicians, composers, and their works, especially in recent years when musicians pushed the limits of “Jewish music” through ever more eclectic borrowing from surrounding cultures. But music can also serve to deliberately preserve and promote Jewish culture in an ever-increasingly assimilated world.

Still, “Jewish music” remains the overarching working term of record in scholarship, the synagogue, and communities, used as shorthand for an expansive and disparate series of conversations. It encompasses a complex and multifaceted relationship between Judaism and sound from ancient times to the present day. This timespan alone attest to music’s role as a product and process through which cultural identity can be constructed and Jewish consciousness kept alive both inwardly and outwardly.

Whether one defines it as music made by Jews, for Jews, in a Jewish style (whatever that may be), or music with Jewish subject matter, there will always be counterexamples for any such singular definition. Jewish music is accepted as diverse, defying any one definition. It ranges from religious music to classical music; it includes folklore and popular music — all relating to the notion of Jewishness. As such, Jewish music is omnipresent in America, ready to be approached and enjoyed with an open mind and with respect.

Tina Frühauf is Adjunct Associate Professor at Columbia University and serves on the doctoral faculty of The Graduate Center of the City University of New York. She is the editor of the award-winning Dislocated Memories: Jews, Music, and Postwar German Culture (Oxford University Press, 2014) and has published widely on Jewish musical cultures. Her book Transcending Dystopia: Music, Mobility, and the Jewish Community in Germany, 1945 – 1989 is scheduled to be released in January of 2021.