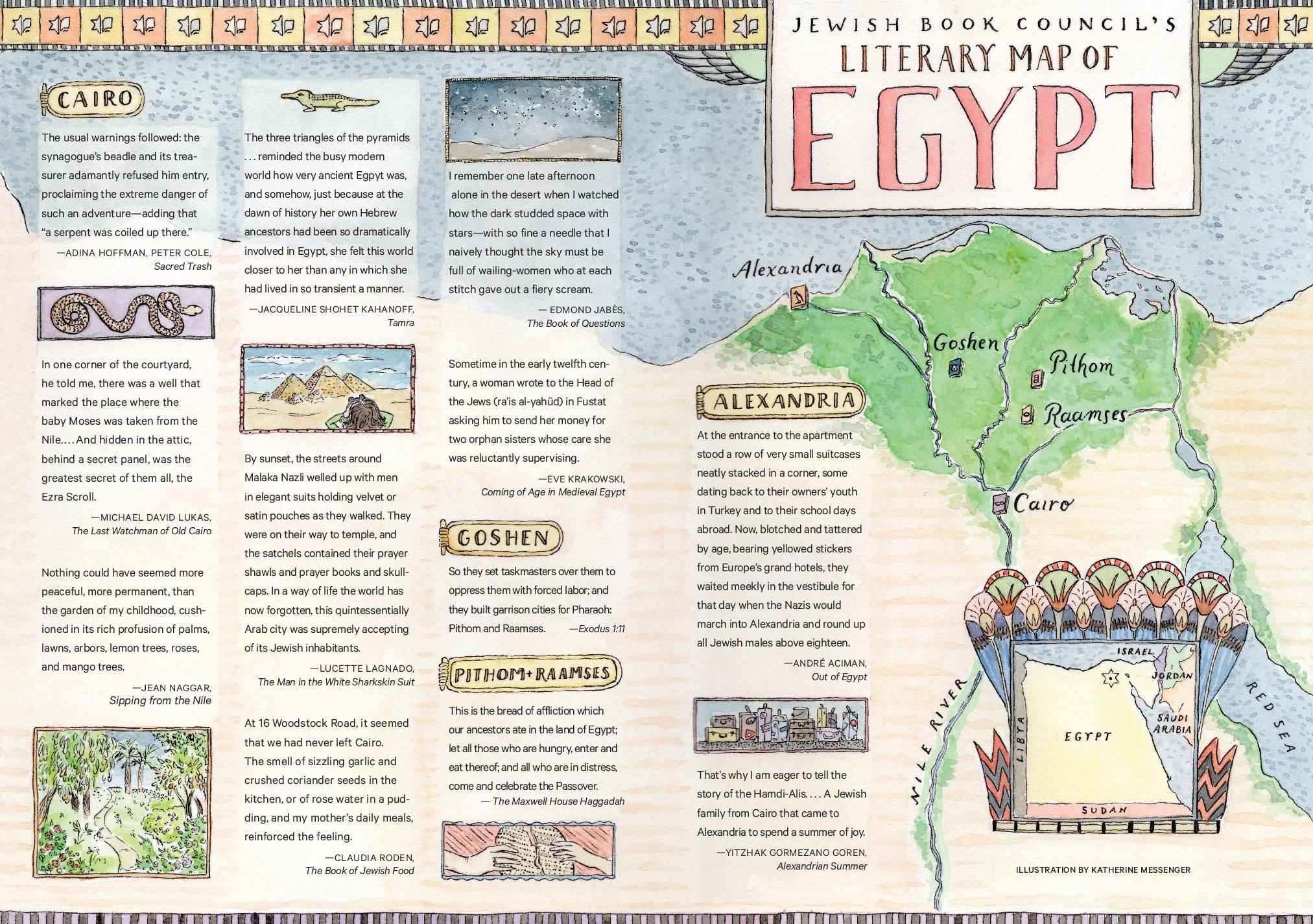

Click here to see larger image. Image by Katherine Messenger

“This is the bread of affliction which our ancestors ate in the land of Egypt,” we read in the Haggadah, which tells the story of the Jews’ biblical exodus from a country where they had risen to be Pharaonic counselors and ended as slaves. The existence of Jews in Egypt — and literature concerning it — stretches far into the past. It is also inextricable from loss and exile.

As Adina Hoffman and Peter Cole relate in Sacred Trash, the Cairo Geniza — a trove of documents and religious texts discarded by Cairo’s Jewish community — was discovered in an attic above the Ibn Ezra Synagogue in 1896. These documents, which attest to a thousand-year span of Jewish life in North Africa and the Eastern Mediterranean, have inspired modern-day writers to examine overlooked eras of the region. Scholar Eve Krakowski, for example, has used them to reconstruct the life of adolescent Jewish girls in Egypt in medieval times.

The 1700s saw an influx of Jewish immigrants — some from Europe, others from Syria, Turkey, Iraq, and elsewhere in the Middle East — who settled in Cairo and Alexandria. Many of them embraced Egyptian nationality, and enjoyed comfort and opportunity for generations. Jacqueline Shohet Kahanoff, born in 1917 in Cairo, grew up at a time when the country was still home to a pluralistic, cosmopolitan society. Although she emigrated when she was in her twenties, she remained deeply attached to her Egyptian origins. For the young protagonist of her unfinished novel Tamra, the “three triangles of the pyramids, outlined against the sky, or dimly perceived through a veil of haze” have become a source of nostalgia, linking her to a more distant past: “because at the dawn of history her own Hebrew ancestors had been so dramatically involved in Egypt, she felt this world closer to her than any in which she had lived in so transient a manner.”

Nostalgia is also a predominant emotion in literature written by Jews who were forced to leave the country decades later. My own paternal ancestors were among those who settled in Egypt in the 1700s. Seated at our seder table in Cairo in the mid-twentieth century, my family never considered the Haggadah prophetic. But in 1956, the religious freedom and diversity encouraged during the Ottoman occupation of Egypt vanished. Within a few years after the Suez Crisis, approximately 25,000 Jews were expelled from or fled the country, many losing their Egyptian passports as well as the land they considered home.

Nostalgia is also a predominant emotion in literature written by Jews who were forced to leave the country decades later.

Intent on gaining a new foothold in the world, Jewish refugees from Egypt focused on rebuilding their lives — maintaining scattered family connections and clinging to familiar rituals while finding homes and careers. At first, many were unable emotionally to look back. But as the years went by, we felt a growing need to preserve the memories that made each of us who we are — and made Egypt what it once was.

Until I read AndréAciman’s memoir, Out of Egypt, I’d never encountered a book that reflected the world of my childhood to me. I marveled at the beauty and evocative energy of Aciman’s writing. Later I discovered other books that gave me a new sense of the complex social, economic, and cultural diversity that informed the Jewish Egyptian experience, such as Joyce Zonana’s Dream Homes, Lucienne Carasso’s Growing Up Jewish in Alexandria, and Yitzhak Gormezano Goren’s Alexandrian Summer.

For American readers, one of the most impactful books on the subject has been Lucette Lagnado’s bestselling memoir The Man in the White Sharkskin Suit.Born in Cairo the year of the Suez Crisis, Lagnado immigrated to New York when she was a young child, and eventually became a reporter for The Wall Street Journal. Her memoir about her father highlights the pain of exile for those who had been thrown into a context for which they had no language. It also introduced readers to a Sephardic history of which many people were unaware.

Poets of the Jewish Egyptian diaspora have also described the anguish of expulsion. Edmond Jabès, for example — whose family’s roots in Egypt stretched back to the fifteenth century — was among those who left Cairo for France in 1956. His later work reflected a deep sense of melancholy, and the realization that exile is a permanent state of mind for Jews no matter their origins or current home.

His later work reflected a deep sense of melancholy, and the realization that exile is a permanent state of mind for Jews no matter their origins or current home.

Jewish Egyptian literature revels in the taste and scent of food. Lagnado recounts that her Syrian grandmother believed apricots were “the fruit of God” and flavored nearly every dish she cooked with their tangy sweetness; both Lagnado and Aciman remember eating pastries in Cairo’s cafes. The most iconic Jewish food writer to have emerged from Egypt is undoubtedly Claudia Roden. Although many of her cookbooks are wide in geographic reach, Roden acknowledges the importance that her formative years in Egypt had on her career. In The New Book of Middle Eastern Food, she explains that the Egyptian megadarra (rice, lentils, and caramelized onions) was known as “Esau’s favorite.” It was a favorite in our household as well as in hers; my grandmother from Damascus pronounced it “mujudra,” and ate it with yogurt.

One of the most deeply evocative novels about Egypt from the past few years is Michael David Lukas’s The Last Watchman of Old Cairo. Intertwining plotlines from three different eras, it follows Jewish, Muslim, and Christian characters connected to the Ibn Ezra Synagogue and its extraordinary geniza. In addition to the country’s unique mix of religions and cultures, Lukas conveys the magic that draws those who left to dream of Egypt still — the Egypt each of us knew and loved, the Egypt that is often entangled with the warmth of home, the mysteries of childhood, and the desire for what is past and will never return.

Jean Naggar is the founder of the Jean V. Naggar Literary Agency (JVNLA), and the author of a memoir, Sipping From The Nile: My Exodus From Egypt, and a novel, Footprints on the Heart. She also maintains a monthly blog: www.jeannaggar.com/blog.