Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

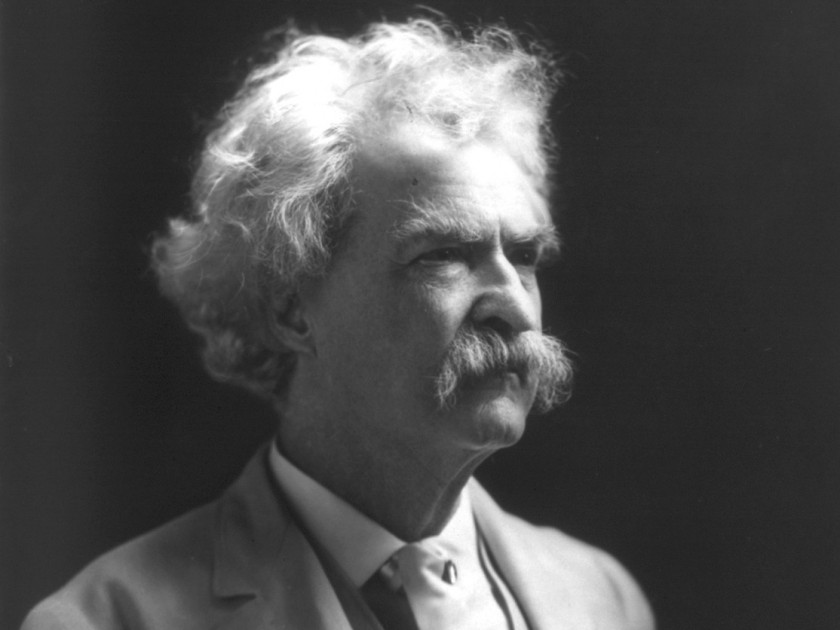

The online literary world has been atwitter (please pardon the pun!) about the changes — some are calling it censorship — that appear in a new edition that presents “updated” versions of Mark Twain’s classic novels, Huckleberry Finn and The Adventures of Tom Sawyer. The change that has attracted the most discussion is the new book’s replacement of the word “nigger” with “slave”; a second modification is the substitution of “Indian” for “injun.” (For general summaries, I’ll point you to news items from The New York Times and Publishers Weekly; for a sample of some of the commentaries, I recommend an AOL News column by Tayari Jones, a blog post by The Christian Science Monitor‘s Marjorie Kehe, and the multiple contributions featured within the NYT Room for Debate forum.)

I’ve followed the flurry of articles and commentaries with interest for many reasons. But here, I want to focus on one. It is both personal and professional, and it involves “Mishpocha,” the concluding story in my new collection of short fiction, Quiet Americans.

In “Mishpocha,” protagonist David Kaufmann, a son of Holocaust survivors, recalls an incident:

It had happened a few years earlier, when [he and his wife] had been visiting [their daughter] at school and spent an extra day and night in Boston on their own, and as they’d walked down a relatively quiet yet decidedly urban street after dinner, a group of teenagers — teenagers whom he’d instantly imagined must cause nightmares for their parents, tattooed teenagers with heads shaven and clothing ripped — strode up alongside them, their ringleader chanting, “KILL THE KIKES, KILL THE NIGGERS, KILL THE FAGS.” And David had seen his wife’s head turn toward them in outrage; he knew that in about one second she would open her mouth with the confidence of a woman with bloodlines rooted in the land of the free and the home of the brave, and so he’d yanked her arm — hard, harder maybe than he’d really had to — because what you learned from immigrant-survivor parents like his was that it was better to be quiet, better not to give crazy people any reason to get any crazier.

Many opponents to the changes to Twain’s work have argued that the word substitutions distort the historical record. As a nervous debut author in an era when using certain words can destroy a career, I draw encouragement from that stance. Because, despite the fact that fiction writers are often instructed not to counter criticisms of their work with the protest that “it really happened that way!”, I will say this about the fictional incident in “Mishpocha“: It really happened that way.

Not to David Kaufmann, of course. To me. And not in the 1880s. During the 21st century. And it happened in one of the most politically progressive communities in the United States: Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Recall, from yesterday’s post, that I am a granddaughter of German Jews who immigrated to the United States in the late 1930s. There’s little doubt that just as this family background has permeated my writing, it has influenced my personality and worldview. Which helps explain why, when those teenagers strode up beside me, and their ringleader recited that awful litany, I, an educated grown-up in her thirties, said nothing. Not one word.

Shortly thereafter (but still about two years before I began writing “Mishpocha“), I received a scholarship and traveled to Prague for a writing workshop. At some point — I no longer recall what prompted the discussion — I mentioned this deeply disturbing incident in class. My classmates, whose backgrounds reflected at least two and quite possibly all three of the groups targeted in the list of epithets, were outraged. But some of them seemed almost as upset with me — for having remained silent — as they were with the person who had uttered the words in the first place.

Absolution came from our remarkable workshop leader: Arnošt Lustig. He listened to me, and he listened to my classmates. And then, this man — who survived Theresienstadt, Auschwitz, and Buchenwald — said that yes, one must fight back. But, he said, one must also live. (I cannot mention Arnošt Lustig without recommending his extraordinary novel, translated as Lovely Green Eyes, which I read in Prague that summer. I treasure my autographed copy.)

Six of my collection’s seven stories have been published previously. Only “Mishpocha” is appearing for the first time, which means that no magazine or journal editors (or paying readers) have yet bothered to take issue with my choice to repeat the same terrible words on the page that I heard on the street. My publisher raised no objections, so to some extent, I had stopped worrying about how this element of the story might be received, and how I might respond to any criticisms it might evoke.

Until now. I harbor no illusions: I’m no Mark Twain, protected partially by virtue of my historical reputation. I’m just a debut author with a book of short stories published by a brand-new press hardly anyone has heard of. But I hope that the support that Twain is receiving now from those who, for a variety or reasons, don’t want to see his writing expurgated will extend to my work, and to me.