Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

This piece is part of our Witnessing series, which shares pieces from Israeli authors and authors in Israel, as well as the experiences of Jewish writers around the globe in the aftermath of October 7th.

It is critical to understand history not just through the books that will be written later, but also through the first-hand testimonies and real-time accounting of events as they occur. At Jewish Book Council, we understand the value of these written testimonials and of sharing these individual experiences. It’s more important now than ever to give space to these voices and narratives.

When every platform on my phone dings and rings, bleeps and burps, I know Friday the 13th will be ominous.

From my first cousin in San Francisco who visited Israel in April I read: Sorry for what is likely an interrupted night’s sleep for all. Hope you are safe.

From my Israeli friend who lives near my mother in northern California:

חושבת עליכם ומקווה לטוב

From my French friend in Paris: Où êtes-vous? comment … donnez des nouvelles, on pense tellement à vous et au courage du pays, notre coeur est avec vous.

From Marcia, one of my best childhood friends, en route to Tel Aviv to celebrate her sixtieth birthday: We turned around after 3½ hours… landed back at LAX… getting off the plane. You guys okay?

A year ago, when she asked me if she and her husband could visit this June, I’d hesitated. How to explain to an American what it’s like to be Israeli right now? To focus only on this moment since no one can foresee the future? COVID was one thing, but October 7 and everything that has ensued over the past 600 something days has hammered home the ambiguity of this time.

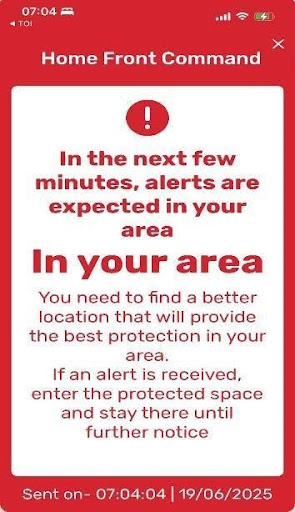

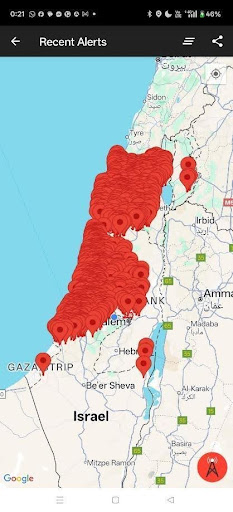

Since returning to the country where my French husband, Philippe, and I met and married in 2011, I follow a strict news diet: only read on a need-to-know basis. The night before, a participant in my yoga and book event in Raanana asked if the event was still happening due to the new security restrictions, and a friend at the US Embassy advised me to cancel it and stay close to shelter. My husband and I had gone to bed sensing impending danger. Thanks to heavy-duty earplugs, used simultaneously to block his snoring and the flight path above us in Tel Aviv, I slept blissfully, unaware of the mayhem in the sky. Unaware of the new dimensions of the wretched power struggle with some of our neighbors. After fourteen years in this country, I am still ill-prepared to respond to the flurry of messages from afar, to the rising anxiety in my chest, to the news headlines: “War Against Iran,” “Inside Israel’s strike,”“Israel launches Operation Rising Lion.” In bed, I shiver, knowing what awaits us, feeling the echoes of last year’s Iranian ballistic missile strike in my bones.

My daughter-in-law and granddaughter spent the past two nights with us since our son has been abroad. When they wake in the morning, I update her about the expected attack and Ben Gurion Airport’s complete closure.

Once again, we are sealed off from the world and surrounded by enemies; our only way out of this volatile region, blocked.

I urge our youngest daughter and her boyfriend to come over, since they have neither a mamad (a room with reinforced concrete walls and ceilings) in their apartment nor a miklat (public shelters, often underground) in their building. None of our kids do. Most apartments built before the First Gulf War in 1991 don’t have any form of shelter, a shocking fact for many.

All photos courtesy of the author

When, mid-morning, a Red Alert warns of an incoming missile, we enter the stairwell, wrongly believing that our building is fortified like a bunker. When it rings again during dinner, I’m sure Shabbat will not be restful. I also feel sure that humanity is reaching the end of a cycle — beginning with us.

The weekend is a blur of unwelcome alerts, disrupted sleep, and ear-splitting booms. As time ticks forward, we lose track of the calendar. Pass the baby from one set of arms to another. Take curtailed walks in our neighborhood.

One late afternoon, Philippe and I help a friend celebrate his birthday, sipping wine and eating apple cake on his sun-drenched balcony. His girlfriend, a psychotherapist, senses my foul mood and invites me to have a private moment with her in their mamad.

“This is a safe space for you to say anything,” she says, setting a seven-minute timer. “Can you tell me something good that happened today or yesterday? Anything?”

I hesitate. “My granddaughter is adorably wide-eyed and curious.”

“Good. What else?”

“My daughter-in-law cooked a delicious fish lunch.”

“Good.” She hands me a throw pillow. “Now I see you’re struggling. I want you to let it out. All of it. Don’t let those feelings get trapped in your body. Vent, scream, cry, bang, squeeze, curse, go!”

As a longtime yogi, this sentiment resonated with me deeply. I squish the pillows sides. “Philippe enrages me. He won’t go into the stairwell with the girls and me, instead staying in our unsafe mamad. Discounting my fear. Like he did during the First Gulf War, when we were newlyweds, wearing gas masks in our sealed room. I feel lonely living with someone who can’t step into my shoes, who leaves me to be the strong one with our girls.”

“Keep going.”

I thrash the pillow. “How can this tiny country handle all this trauma? How can anyone deal with so much loss — of sons, daughters, mothers, fathers, siblings, friends? How can we have enough first responders when missiles wipe out neighborhoods, leaving those who survived homeless while searching for those who didn’t?”

Tears cascade down my snot-filled face.

“Good!”

I reach the end of my diatribe.

“Okay, now look around the room and tell me one thing you like.”

I scan their space — the wood desk, swivel chair, sofa bed.

“The fridge cracks me up. So out of place.”

“Good. Do you feel better?”

“תודה רבה,” I say while leaning in for a hug.

But the lightness doesn’t last. A middle-of-the-night siren shrieks like a witch. Going to bed becomes terrifying, but so does waking up.

Since daytime seems safe, my daughter and I go out to get air and exercise. Sidewalks that are usually bursting with tattooed locals, energetic tourists, suntanned surfers, and multilingual foreign workers now feel like a ghost town. We tiptoe around shards of glass and see broken windows on a redone historic building, a mini market, a chic bakery. We stop to acknowledge the destruction, buildings crumbled and bent beyond repair.

My mom video calls. The phone shakes from her benign tremor. “What’s new?” she asks in her chipper voice.

I don’t want to tell her what it’s like, how vulnerable I feel.

If I could leave, I would.

But no one’s going anywhere.

For the third night in a row, we are up and out the door at 12:02 a.m.

We accuse Hamas of using humans as shields, digging tunnels under hospitals. But I wonder, isn’t the Israeli government doing the same thing by leaving a massive military base in the center of Tel Aviv, building new residential apartments on its edge? As for tunnels, how can any hostage survive living like this, timeless, underground, in blackness?

I pack two bags. The first is a go-bag with passports, birth certificates, US social security cards, jewelry, cash, keys to my mother’s condo in California, and our recently updated wills. The second is a carry-on full of clothes. I leave them on the floor of our mamad, which doubles as our walk-in-closet.

Mostly it is just vital businesses like food markets and healthcare clinics that are open. But some cafes, restaurants, and wine bars defy these orders so people can gather, drink coffee, and just feel normal somewhere.

I meet a friend at a close-by cafe. We talk about the mundane (our new progressive glasses frames) and the meaningful (where would we live if we could leave) until another friend joins. She is US based but comes for extended stays and arrived before and stayed after October 7 and again now. Something about this place makes some people feel more alive — like their presence matters in a different way.

Night after night, I pop a different pill — a mix of homeopathic pills and CBN-infused gummies from across the world. I wonder: Will I ever be able to sleep on my own again?

Finally, our son secures a flight from Athens to Aqaba, Jordan, along with an old friend from his army unit. Together, they will cross the border into Eilat and ride a bus to Tel Aviv.

But who knows when. Red Alert. In the stairwell, the booms undo me, unglue me. My daughter-in-law hands my granddaughter to me. When I think of the world we are handing to our children and their children, I shudder.

“Let’s go to the parking lot,” Philippe suggests. “We won’t hear anything.” He joined us after I begged him.

On the first floor of a four-level garage under our complex, I am surprised by the scene: people of all ages and colors, shapes and sizes stand, sit, and wait. Alone, together.

After the all-clear alert, we trudge upstairs.

I doom scroll. “US struck three nuclear sites in Iran.” What if Israel’s Operation Rising Lion triggers World War III?

I complete the US Embassy forms for evacuation and EL AL rescue flights, then ask my husband if he’d leave with me.

“I don’t feel the need to go.”

“Who do you love more, Israel or me?” I ask, not for the first time in three and a half decades of matrimony.

“That’s unfair. This isn’t the time to judge each other. I’m not judging you if you go, but you can’t judge me either for staying.”

Friends and strangers have called me brave. A word I do not associate with myself. Until now. Now I feel it in every cell: If I can go, I will, even if alone.

Our son arrived in time for the last twenty-four hours of missiles. Reunited, we ran to the parking lot at 5:44, 6:23, 6:39 in the morning.

In the minutes leading up to a ceasefire, four were pronounced dead in a direct hit on an apartment in Be’er Sheva. May their names never be forgotten: Eitan Zacks, his mother Michal, his girlfriend Noa Boguslavsky, and their neighbor, Naomi Shaanan.

Just because we haven’t lost a loved one or experienced damage to our house, doesn’t mean we are okay. Just because we are safe, sound, and unscathed doesn’t mean we are okay. I am not okay. No one around me feels okay.

From one second to the next, the government commands us to act normally. Send kids to school, go to work, return to the gym. But what does “normal” mean anymore?

While Jews abroad feel reassured that a full-blown war did not explode, we see it differently. For the past 628 days — and still counting — we’ve grown accustomed to a distraught new normal with occasional missiles, missing hostages, and dying soldiers. For us, this was a war within a war.

Messages from well-meaning friends flood my phone:

Since their flight returned to Los Angeles, my friend Marcia has been checking in daily: My heart goes out to you on ‘getting back to normal’ or ‘abnormal’. I can’t even imagine the transition 💔.

The transition is jarring. Our nervous systems ache from the whiplash. The fallout will take months for us to unfeel in our bodies.

Am Yisrael is here but changed. Those of us who endured this attack are as shattered as the windows. How long it will take to mend and feel whole again is impossible to know. Because when it comes to the future of the state of Israel — of the Middle East — no one knows.

The views and opinions expressed above are those of the author, based on their observations and experiences.

Support the work of Jewish Book Council and become a member today.