Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

Polly Zavadivker is the editor and translator of the recently published 1915 Diary of S. An-sky: A Russian Jewish Writer at the Eastern Front. She is blogging here all week as part of the Visiting Scribe series on The ProsenPeople.

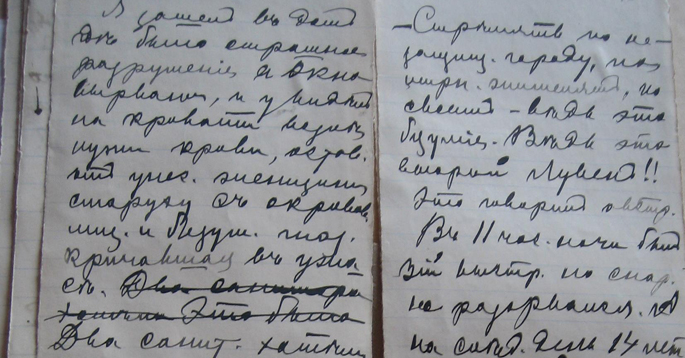

An-sky’s notes taken in Tarnow, Galicia, February 14, 1915

An-sky’s notes taken in Tarnow, Galicia, February 14, 1915

What does it mean to write in a war zone? For Russian Jewish writers during the first half of the twentieth century, this was not a hypothetical question. Some of the best known writers of the Russian Jewish literary canon — among them S. An-sky, Isaac Babel, and Vasily Grossman—witnessed and survived massively destructive wars of the twentieth century as they wrote about them. An-sky traveled across the western Russian Empire and Austrian Galicia as a relief worker from 1914 to 1917; Babel crossed from Ukraine into Poland as a political officer and journalist with the Red Army in 1920; and Grossman served as a war correspondent behind front lines from Stalingrad to Berlin for the Soviet newspaper Red Star between 1941 and 1945.

These writers entered the war zones with the intention to write about them. They undertook journeys across the cities, towns, and villages of war torn Eastern Europe at great personal risk. Like disaster tourists at a time of almost global disaster, they became witnesses to colossal human catastrophes that unfolded before them. As writers, they turned aside from the horror they saw in order to document it in ink and pencil, on the small pads of paper and notebooks that they carried on themselves. They wrote while sitting in military trucks, trains, and horse-drawn carts, and in hotels, military headquarters, and civilians’ homes. From the notes they hastily scribbled at the time of war, they created stories about what they had seen and remembered. Their notes and later stories became first drafts of history.

As Jews, writers like An-sky, Babel, and Grossman also felt compelled to represent the experience of Jews in Eastern Europe during wartime. Their war writings are therefore also histories of the Jewish experience of watershed events in twentieth-century history. Jewish chroniclers of catastrophe traversed the heartlands of devastation, along the frontier that lies between historic Poland and Russia (the Pale of Settlement, as it was known before 1917). These borderlands — in today’s Ukraine, Poland, Belarus, and the Baltic states — were home to the largest segments of Europe’s Jewish populations until 1945. Consequently, they became the places where the largest segments of Europe’s Jewish population fell victim to violence in each war. During World War I, the Russian military deported nearly half a million Jews from northwestern Russia and Galicia to the Russian interior and carried out hundreds of pogroms; in 1919 and 1920, the Jews of Ukraine and Belarus fell victim to devastating massacres at the hands of Russian, Ukrainian, Cossack, and Polish troops during the Russian Civil War; during World War II, German Einsatzgruppen units shot 1.5 million Jews just in occupied Ukraine alone.

Russian Jewish war writers chronicled each of these catastrophes, and they were able to gauge the extent of destruction to Jewish life and culture in these regions not only because they had witnessed the effects of war firsthand, but also because they possessed intimate knowledge of these places. They were native sons, born and raised in the shtetls and cities of the territories that became war zones between 1914 and 1945.

Russian Jewish war writers chronicled each of these catastrophes, and they were able to gauge the extent of destruction to Jewish life and culture in these regions not only because they had witnessed the effects of war firsthand, but also because they possessed intimate knowledge of these places. They were native sons, born and raised in the shtetls and cities of the territories that became war zones between 1914 and 1945.

These writers knew what war meant, then, for the Jewish people. They understood that battles between armies result in more than the death of human lives; war also destroys culture and civilization — it destroys history. How will the Jewish people’s experiences of war be remembered if the victims’ stories are lost? If their stories do reach audiences in the future, will readers believe what they read? And will they have the capacity to comprehend what has taken place? The writers pursued these questions with a sense of urgency during and after the different wars. The diaries, letters, poetry, stories, journalism, and notes they left bring us as close as we can come to those dark moments in history, the starting points for understanding the Jewish experiences of the series of wars that ended with the total destruction of Jewish civilization in Eastern Europe during the first half of the twentieth century.

Polly Zavadivker is Assistant Professor of History and Jewish Studies at the University of Delaware.

Related Content:

Polly Zavadivker is Assistant Professor of History and Jewish Studies at the University of Delaware. She is the editor and translator of the recently published The 1915 Diary of S. An-sky: A Russian Jewish Writer at the Eastern Front (Indiana University Press). Her work has been published in journals including East European Jewish Affairs, The Simon Dubnow Institute Yearbook, Russian Review, and others. She is currently at work on a manuscript entitled “Blood and Ink: Jewish Chroniclers of Catastrophe in Twentieth Century Russia.”

On Writing Catastrophe: Jewish Chroniclers of War in Twentieth-Century Russia

Jews in the Rubble: A Reading List of Soviet Jewish Eyewitness Accounts of World War I