Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

Jewish young men wearing yarmulkes stand in front of a kiosk and hold up a newspaper with an article about Karl Adolf Eichmann in 1964 Tel Aviv

Van de Poll photo collection

The first Holocaust survivor that I ever saw was a woman in Jerusalem. It was 1961, the year of Adolf Eichmann’s trial, and she was carrying a bag of vegetables as she crossed the street. The sunshine seemed to illuminate the blue numbers on her arm as she made her way across the road.

Back in New York City where I was from, I had never seen a Holocaust survivor to my knowledge. Perhaps because they wore long sleeve blouses and jackets instead of lightweight summer shirts that were suited to the warmer Jerusalem climate. Or maybe they were determined to keep their story a secret.

I had traveled to Israel with a dozen other college students on a fellowship to study politics, economics, and Hebrew. We were housed in the neighborhood of Rehavia, home to many German Jews who had managed to escape Hitler through their formidable resources – some were even able to send their baby grand pianos to their new homes in Israel.

It was a very tense time. The radios were blasting news of the Eichmann trial. Walking along the streets of the Old City of Jerusalem, one could hear the poignant testimonies of survivors from loudspeakers mounted above some of the stores. The cafes along Ben Yehuda Street were filled with Holocaust survivors, smoking cigarette after cigarette and drinking glass after glass of black coffee. They seemed to be leaning in toward each other, whispering confidences.

I understood Hebrew and I admit to eavesdropping on their conversations. I heard how they had managed to escape their one room apartments in the ghettos, how they had survived in the camps, and the miles of marching they endured with no food or water. Some spoke of digging pits and graves for their own family members, their neighbors, their fellow Jews. Others spoke of how they snuck off into the woods when the guard turned his head for a moment. Others talked about stealing a few pieces of dry bread and hiding them in the wall to prevent themselves from starving. Each story is deeply embedded in my memory, and my eyes teared up as I listened to them.

It was a very tense time. The radios were blasting news of the Eichmann trial. Walking along the streets of the Old City of Jerusalem, one could hear the poignant testimonies of survivors from loudspeakers mounted above some of the stores.

When I returned to America after the fellowship program, I wanted to write about what I had heard and what I had seen but somehow I felt paralyzed. There was too much pain to put into words, and as a young journalist I was desperate to get it right, to tell their stories as truthfully as I had heard them. But I had taken no notes and every time I sat down to write, I could not tell their stories.

About ten years later, a distant cousin whom I had never met sent me her mimeographed memoir about hiding in the Lvov Ghetto from 1941 to 1944. Her name was Rose Wagner and her daughter had helped her translate it to English. It was 140 pages in length and at the back of the memoir was appended two pages listing the names of her family (on her mother and father’s sides) who perished in the Shoah. There were thirty-six names of members of my grandmother’s family on the list. Rose was the only survivor.

I read the memoir several times, it’s opening: ”April 1943. The world is on fire. The flame of World War II, ignited on September 1, 1939, has taken on the dimensions of a gigantic blaze that is destroying daily thousands of human lives along with all their earthly possessions.” And several paragraphs later, Rose wrote, ”I am not exactly familiar with the present conditions in the other countries of Europe. However, judging by what is happening in Poland – in the larger cities like Warsaw, Lvov, Krakov, as well as in the small towns — I am, unfortunately, very well aware that wherever the Nazi forces have spread their brutal might, the fate of our people is doomed.”

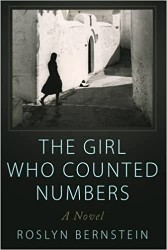

Reading her memoir finally pushed me to write my novel which was inspired by so many of the stories I heard whispered on the streets of Jerusalem–The Girl Who Counted Numbers, set in 1961 Jerusalem during the Adolf Eichmann trial. Rose’s memoir connected me directly and deeply to my relatives who perished in Auschwitz whom I never knew.

The words of the survivors I’d heard in 1961 affected me deeply and when I sat down to write my novel, pieces of their stories poured out of me.

All of these stories of the Shoah will be remembered.

The Girl Who Counted Numbers by Roslyn Bernstein

Roslyn Bernstein has been a storyteller all her life, sometimes working for a true account in the narrow sense as a journalist when it’s reporting or history, and sometimes in a wider, more resonant sense when composing poetry, short stories, or a novel. As a journalist, she has reported in-depth cultural stories for venues including Guernica, Tablet, Arterritory, and Huffington Post. Sixty of her online pieces were reprinted in an anthology, Engaging Art: Essays and Interviews From Around the Globe. While reporting on all forms of art and architecture, documentary photography has been a major subject of Bernstein’s writing and teaching since the 1970s.She is the author of a collection of linked fictional tales, Boardwalk Stories, set in a seaside community during the 1950s, and the co-author with Shael Shapiro of Illegal Living: 80 Wooster Street and the Evolution of SoHo, which focuses on one building to tell the story of SoHo’s transformation from a manufacturing district to a live-work arts community. For most of her career, she taught journalism and creative writing at Baruch College, CUNY where she was the founding director of The Sidney Harman Writer-in-Residence Program. The Girl Who Counted Numbers was inspired by the seven months that Roslyn Bernstein spent in Jerusalem in 1961. She has tried to be attentive to historical details although the story of Susan Reich, her family, and friends is fictional.