Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

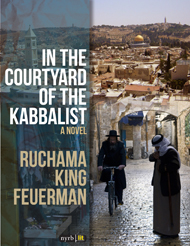

Earlier this week, Ruchama King Feuerman wrote about stories from her mother’s Moroccan childhood. Her most recent book, In the Courtyard of the Kabbalist (NYRB LIT), is now available. She will be blogging here all week for Jewish Book Council and MyJewishLearning.

When I was a kid, every morning I’d watch my father shave from my perch on the rim of the bathtub. After he washed and patted down his face, he’d squeeze body cement onto the bumpy pale wedge where his real ear used to be. Then he’d paste on his rubber ear, which gave his head a nice gluey smell. As for the prosthetic ear, it was unnoticeable, that is, until you noticed it, and then it lent him a curious air, like a man patched together from scraps and pieces.

When I was a kid, every morning I’d watch my father shave from my perch on the rim of the bathtub. After he washed and patted down his face, he’d squeeze body cement onto the bumpy pale wedge where his real ear used to be. Then he’d paste on his rubber ear, which gave his head a nice gluey smell. As for the prosthetic ear, it was unnoticeable, that is, until you noticed it, and then it lent him a curious air, like a man patched together from scraps and pieces.

He’d stand in front of the bathroom mirror, inspecting his ear to see if he’d placed it well, and then stories about his own life would start coming: the dirt poor Depression years when his mother had to use burlap bags as underwear or diapers; how he learned to wrestle so no one would ever again pick on him because of his ear; the twenty-nine relatives who all lived in one small house in the 1930s, the whole crew subsisting on Grandpa Sam’s single salary as a tailor; how he became religious in his late twenties and so set in motion a generation’s return to Judaism. Later, around the Shabbos table, he told us Hassidic tales and epic scenes from the Bible. Truth be told, it didn’t matter what he was saying. He knew just how to pause to make us yearn for the next sentence. He was a born storyteller.

My father’s stories insinuated themselves so powerfully into my psyche, that I’ve often felt I’m living two existences, my own and his. I’ll be scraping the vestiges of oatmeal out of a pot, going over my teaching schedule for the day, when suddenly I’m back in the summer of 1934. I see my father on a July afternoon, playing with rocks piled high on the corner of New Hampshire Avenue. My eyes swerve past him toward the end of the block, and then I see it, a ‘32 Plymouth barreling down the road. I want to shout, “Get up, run, Dad, stop playing with those stupid rocks, for God’s sake!” but he keeps piling those rocks high, until the Plymouth slams and skids into him, even as the driver slams on the brakes. He can’t die, I know he can’t die, because how else will I get born, and when the ambulance comes for him, he’s still breathing, but his ear hangs by a spider thread to his skull. I stand there at the sink, my heart rattling crazily in my chest, and finally shut off the faucet.

Over time, as I listened to my father’s sagas of horrible health (at any point in the year he could show up at a hospital and get admitted), a doomed marriage, and silly jobs that never matched his talents, I would think that no father in the world had suffered as much as mine. In my eyes, to have survived what he had, along with his heroic struggles to put bread on the table, made him a mythic character. With every tale he told, I couldn’t help but hear not just his stories but his Story, of all his life struggles, and to me they became one. Always I felt a scorching pity.

There’s a kabbalistic concept, hamtakat hadin, sweetening the judgment. In my own stories, the ones I write, I find there nearly always has to be some scrap of sweetness or redemption. If I look carefully, I know somewhere, someplace in the pages I’ve written, I’m saving my father, finding the poignancy and sweetness in the judgment of his life, of all our lives. It’s a compulsion of sorts – saving my father.

One of my main characters in my new novel, In the Courtyard of the Kabbalist, is a man called Mustafa, whose job is to pick up trash on the Temple Mount, or, as he calls it, the Haram al Sharif. His head is twisted permanently over his right shoulder. Walking is difficult, eating even more so. His mother, ashamed of him, won’t let him return to his village.

People who have read the book often ask me: How did you slip into the mind of someone so radically different from yourself?

I too had thought it would be impossible and so I put off writing about this Arab man who for years stalked my imagination. How strange, how wonderful to discover then, as soon as I began to put words down on paper, that I felt so close to Mustafa. He was as painfully close and tender to me as my own father.

Ruchama King Feuerman’s celebrated first novel about matchmaking (Seven Blessings, SMP) earned her the praise of The New York Times and Dallas Morning News, and Kirkus Reviews dubbed Feuerman the “Jewish Jane Austen.” Read more about Ruchama King Feuerman and her newest novel, In the Courtyard of the Kabbalist, here.