Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

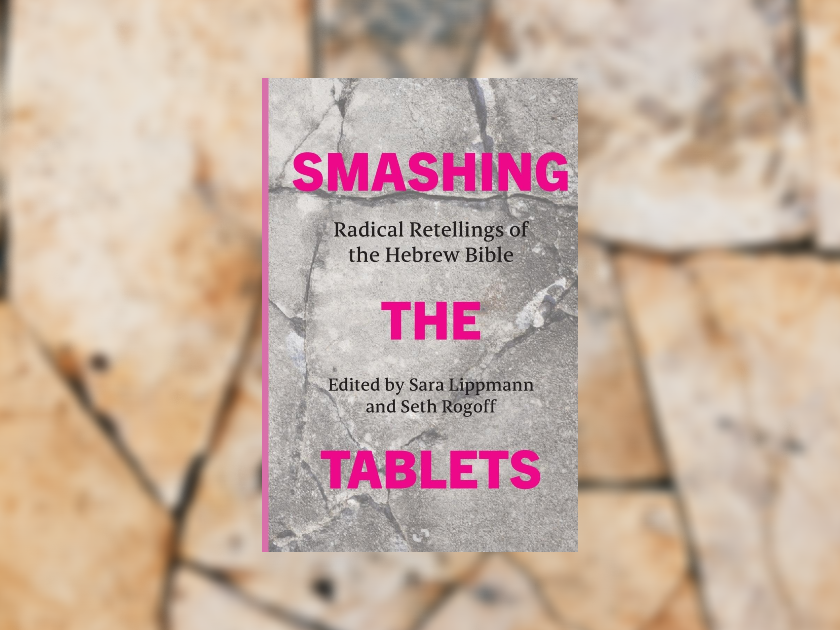

Smashing the Tablets: Radical Retellings of the Hebrew Bible is a bold, new collection of twenty-three writers’ responses to biblical stories. Through fiction, creative nonfiction, and poetry, these invigorating pieces invite readers to reconsider and reflect on storytelling itself. JBC spoke with the editors of the volume, Sara Lippmann and Seth Rogoff, on the origin story of the project, the similar themes that emerged across pieces, the the power of retelling, and more.

Simona Zaretsky: Smashing the Tablets is an exciting anthology composed of twenty-three pieces (and a foreword by Shalom Auslander) that span time, place, and perspective. What was the impetus for creating this collection?

Seth Rogoff: I have been working with biblical texts as part of my creative process for many years. Often, I start a novel with a few elements in mind, one of which is the basic scenario or situation of the novel and another is a biblical story that relates to the idea or scenario, often not directly but metaphorically or allegorically. During the writing, I rework the biblical material, turning it around, flipping it over, trying to get a sense of its dimensions, its depth. Often the most important dimensions for me become what’s absent, what’s implicit, and the tensions or contradictions in the piece. This has been an inspiring way of working, and I thought, yes, the biblical text is made truly alive in this way. It is organic — shifting, changing with each encounter. It has changed for me so much that I can hardly distinguish the original from the layers I have set upon it. When I read the story of Jacob’s ladder, a key motif of my novel The Kirschbaum Lectures, I see not only the short biblical text but also the many ways I have reimagined it. These alternative readings have fused with the “original” for me. What would happen, I thought, if I asked writers whose work I love to read and deeply respect to encounter a biblical text of their choice with the intent to explore it?

This process could be done with any text, really, but doing it with the Bible, for me, has a broader spiritual dimension. I am searching for a relationship between the human and the divine built on foundational values such as egalitarianism, generosity, care, and peace, ones that reject violence, hierarchy, and authoritarianism. Unfortunately, the values of hierarchy, tribalism, and authoritarianism (big and small) dominate today’s religious culture. At present, powerful Jewish factions are espousing a violent, authoritarian ideology. This is not my Judaism, and I am not prepared to renounce my Judaism entirely because others choose to “practice” it in these ways. If we want a different Judaism, we need to build alternative foundations. Can we find a faith that’s good, that’s just, that’s universal? I think about the encounter between God and David in Second Samuel after David takes possession of the wife of Uriah the Hittite. God tells David a parable of a rich and poor man, how a rich man takes the one and only lamb from the poor man to feed a traveler, instead of taking from his own flock. David, enraged, calls for the rich man’s death. God responds, “That man is you!” If the entirety of Judaism was this one moment, I would be the most fervent believer. How opposed is our current society, and our current Judaism, to this sentiment! There are Jews today who would not only celebrate the stealing and killing of the lamb but would say that’s not enough, the poor man himself should also be destroyed.

Sara Lippmann: When Seth first approached me, I balked. Who, me? I’m no Torah scholar. I was a Hebrew school delinquent. But as we spoke, I began to understand that my knee-jerk impulse – to leave it to the “experts” – was precisely what he was pushing against. The whole idea of the project was to remove the Torah from its lofty pillar, from its realm among the strict interpretationists and to invite all of us in. I realized part of my whole rebellion could be attributed to an anger and resentment at having been raised with this narrow messaging, that I was somehow not worthy, even though I’d been subjected to these stories my whole life. Ever since I was little, I’ve been pissed off by an assumed passivity and empty compliance with religion and ritual, dissatisfied with rote authoritative answers to my questions: “Because it is written.” And yet, ironically, in my twenties, I spent months reading the Tanakh in my own self-imposed literary inquiry. I realized that this inherent blend of curiosity and resistance to the status quo made me a prime candidate for the project.

SR: I’d just like to briefly add that even though I approached Sara with the initial conception, it continually evolved during the years we worked on it together. The process was such a rewarding collaboration, and I learned so much from Sara.

SZ: What was the process like of putting this collection together?

SR: The spirit of radicalism guided the decision-making. I felt that rather than impose a notion of “radicalism” on authors, it was more radical, and more appropriate, to provide the space for authors to interpret this concept for themselves. Sara and I wanted to cover diverse parts of the biblical text and avoid redundancy, but otherwise we gave authors room for exploration. Important to our process was finding a wide range of voices and perspectives, and I think we achieved this. The collection is not a manifesto from a single ideological or interpretive viewpoint. In many ways it is a cacophony, but often the deepest rhythms are found beneath such noise, if we have the patience to disentangle it.

SL: I felt deeply committed to bringing in as many different writers, from as many different backgrounds and different stages in their careers as we could. Obviously, we were limited by space, time, and word count, and so in many ways this volume barely scratches the surface, but it was really important to me to look beyond the cis, Ashkenazi, mid-life Brooklyn writer (to whom I mean no shade!) and to intentionally broaden our scope in the spirit of heterodoxy. Once we had a core list of contributors, we were able to take the project out on proposal. After SUNY Press signed on, that list continued to grow. This is my first collaboration, and my first time editing an anthology, so there was a lot to learn and juggle, but it was incredibly rewarding to get to work with and be nourished by so many talented writers. With Seth in Prague and me in Brooklyn, there could be a natural lag in our communication, which perhaps ran at odds with how accustomed we’ve become to rapid fire responses, but there was something fitting about the pace, how it encouraged its own thoughtfulness and creativity. Patience is an overlooked gift. We met regularly on Zoom throughout the years-long process, often as my day was starting and his was ending – and those conversations always left me energized and buzzing with new ideas.

SZ: The book begins with Shalom Auslander’s humorous and insightful dissection of biblical storytelling. This piece asks readers to confront biblical storytelling, as a tool for teaching children, but really also as a way of living. How did you approach the framework for this collection? Were there any challenges or unexpected insights?

SL: I don’t know that we envisioned it as a “tool” for anything – living or teaching – but more as an invitation for active engagement. That is, instead of protesting via dismissal or turning away, the protest can flourish inside the conversation… and not merely inside of it, but explode and expand it. While I do believe there is plenty to learn from the innovative and courageous ways these writers approached their material, trying on and sloughing off, inverting or reimagining and otherwise making their own, it’s hardly an instruction manual. To the contrary, the pieces merely hold up a mirror, and perhaps encourage us to peer deeper into our fallible, vulnerable selves, to embrace and not cast off any part of the very messy stuff that makes us human.

In terms of challenges and insights, one thing we began to realize as the anthology took shape was its natural lopsidedness. It’s Genesis heavy, for good reason: the first book of Moses contains some of the most widely read and most narrative stories, and also is rife with drama. Expulsion! Floods! Near human sacrifice! Many of these tales are already cemented in the collective consciousness. I don’t think we have anything from Leviticus, Numbers, or Deuteronomy. On the one hand, this could be seen as a glaring gap, but on the other hand, a gaping hole in our anthology feels consistent with other Biblical gaps. We had no pretense about creating something “whole.” The unevenness feels integral. As we began to order the collection, we were faced with the challenge of how to clearly show the new pieces in conversation with the old? That’s when we came up with the idea to assign an epigraph to each. What salient line from the text most resonates? Seth and I split up the task and then reviewed them, and here’s where we discovered another fun challenge – we were not working off the same edition of the Tanakh, which meant there were minor variations in the translations, so we had to go back and agree upon a version, and then smooth things out for consistency, which was a choice, but which again only underscores the fact that nothing is absolute.

SZ: In the introduction, you invoke the idea of “the power of creative reading.” This is such a striking idea, could you speak a bit more about it and how you see it at play in Jewish storytelling today?

SR: This is a notion I feel quite strongly about, mainly because I think creative reading is an endangered practice. Most of us are aware that reading is in steep decline in today’s society, and has been in decline for a long time. Increasingly, our educational systems prioritize instrumental reading, reading to gain informational content. The laziest and most problematic type of reading is what’s done in what we call “social media.” This is a type of reading that has very little to do with what we called reading in the past. Instead, it is an activity meant to generate a quick emotional impression, which then fades, replaced by the next. Meaning is decontextualized, even though context itself becomes generic and universalized. The more superficial the text is, the better. Creative reading is fundamentally different. It is a generative process, and in my view an artistic practice. It takes the text as material; it adds labor or work; it combines the text with other materials. It creates structures of interpretation and meaning. These structures might collapse immediately, replaced by new ones. They might be constantly reshaped. The process takes time, requires commitment, requires openness, creative engagement, intellectual and creative flexibility, patience, respect for the text, for the text as “other,” respect for the self, for the process of self-creation, self-decreation, the flux of the self as it absorbs and reshapes that which is beyond its tenuous borders. Creative reading is a process that pushes back against simplification, against the divisions of inside and outside, self and other, us and them. It desires depth and rejects superficiality. For me, creative reading is a way of life, not only a strategy to read and write, though I feel I can actualize this practice best when working on a novel. The novel writing process becomes a mode of reading, and I think that’s why, despite the otherwise practical uselessness of a novel and its rootedness in a kind of bourgeois reactionary culture, I still love it. Writing-as-creative-reading has, for me, an ethics, which are grounded in what I find best in humanism. In terms of its relationship to Jewish storytelling, I find it vital. In a world governed mainly by closed meaning and dogma, a world in which reading is instrumentalized for the purposes of division and domination, for the purposes of rigid identity formation and a closed sense of self, a world which is spiraling into catastrophe, what do we need more than this? Jews have been some of the most creative readers in world history, and as this anthology indicates, some still are. In this regard, two pieces in the anthology that keep coming back to me over the last years are Michael Zapata’s loose response to the flood narrative and Rosebud Ben-Oni’s vision of a dark and decaying Eden. Ben-Oni’s world, apocalyptic and brutal, feels like one of the most accurate representations of today’s reality I have encountered.

SZ: Ever-shifting power dynamics are present in so many of the pieces. It shows up in interpersonal relationships, between individuals and societal forces, and at times in spiritual aspects where the figure of God wields near complete power. Could you explore this tension?

SR: The issue of power is at the heart of the Bible. The creation story is, in a sense, the beginning of a power struggle between God and human beings. In the typical interpretation, the Hebrew God differs from the non-Hebrew gods in God’s omnipotence. There is no question about God’s authority. God’s reign is absolute. And yet, the text is full of slippages, moments of ambiguity, fear, and questioning of God’s power. In my view, the acceptance (and celebration) of the absolute authority of God over human beings creates a hierarchically organized religion, which supports social hierarchy. On the other hand, if we don’t accept the basic “original” hierarchy and instead start to probe the tensions and fissures in these relationships, we can unearth more radical, anarchic sensibilities. The existence of these sensibilities in the text indicates that the canonized bible is not a closed text. The Bible contains ideas about hierarchical and authoritarian power, but it also contains their negation. It is up to us to decide what ideas and values matter. We can rewrite the entire Bible from this vantage point, and it will be just as real as the currently canonized version. We can all play the role of the prophet Ezra.

SL: Rabbi Sharon Brous recently said that “our agency is our most sacred inheritance” – and that sounds about right to me. Chalking it all up to divine will absolves the self of responsibility, thereby creating a vacuum for power grabbing and corruption. The mere notion of God’s degree has dangerous and violent implications, which we cannot afford, not ever, and certainly not now. It seems we always have a choice: to be kind, to be loving, to act, to look beyond the boundary. Most of the pieces embrace the function of choice as they revisit dynamics between mortals: father and son, daughters and father, wife and surrogate, rabbi and pupil, lover and king, etc.

The issue of power is at the heart of the Bible. The creation story is, in a sense, the beginning of a power struggle between God and human beings.

SZ: Seth, in your piece, “Cain and Abel,” the character of God is villainous, taking out ire on an unwitting, devout Cain. Cain shuffles between cities, always the scapegoat with no hope for justice. I was struck by the deep sadness of Cain being unable to go home and mourn his brother’s death with his family. What were your influences in portraying God and Cain in this way?

SR: Cain has always fascinated me from the time I was a young boy in Hebrew school. Then, and now, I could never understand why he would have killed his brother. I mean, I have two brothers, and even though I often felt a certain way about them, I never had the urge to murder either of them. To believe in the story, one has to believe in a kind of inherent evil in Cain rather than a “motivation.” There is an implied motivation, but for me this only highlights the lack of motivation. Also, as a boy, I felt connected to Cain’s punishment, his rootlessness, his wandering, his invulnerable vulnerability. In this story in the anthology, which is a small fragment from my novel The Castle, I wanted to imagine a different Cain. And to imagine a different Cain meant to imagine a different God, and a different relationship between them. What’s striking in the first pages of Genesis is the amount of conflict between people and God. Adam and Eve, of course, famously disobey and violate God’s rules. God enforces the strict division between humans and the divine by denying Adam and Eve access to the Tree of Life, thus immortality. God then banishes the pair from Eden and creates the world’s first territorial border. Cain becomes, then, the original trespasser, the original stranger, the forefather of the nomad, the wanderer, the migrant, the immigrant, the outsider. As such, he is the archetypal disruptive force. He enters a social system and by his mere presence shifts that system. This is the Cain I discovered through Kafka’s novel The Castle. And my novel of the same name is partly an imagining of Kafka’s K. as Cain (or in German Kain). Whether he knows it or not, my Cain is an anarchic force, containing the pre-creation chaotic force of the watery “deep.” Creation means authority and hierarchy; chaos means equality and freedom, freedom primarily from our rigid sense of self.

SZ: As you mention in the introduction, many of the pieces focus on narrative gaps or figures who were previously nameless. Were there any figures you wanted to ensure were highlighted in a contemporary interpretation? Were there any pieces that surprised you?

SL: It was fascinating to see which stories were pounced on right away, and which stories were left un-retold. For example, I thought for sure someone would snatch up Jonah and his famous preposterous fish, but no dice. While we do have Moriel Rothman-Zecher’s beautiful take on Jacob wrestling the angel – at a queer nightclub – no one explored Jacob and Esau and the classic case of the stolen birthright, which shocked me. Joseph, too, is noticeably absent. Instead of the story of Joseph’s dreams, however, we have Sarah Blake’s ferocious first-person story of his half-sister, Dinah, raging front and center, which feels completely in line with our mission. Which is to say, in thinking through this question, it feels completely in line with our project that so many of the more iconic stories one might expect to see were sidelined to make room for lesser known tales or characters, particularly female characters, that receive only a passing mention, if that, in the original text. I’m grateful for erica riddick’s centering of overlooked matriarchs Bilhah and Zilpah. And who was Jepthah’s daughter, anyway? That’s what this was all about.

So many pieces surprised us in exciting and challenging ways, which was one of the most delightful aspects of the process. When a new piece arrived in our inbox, it was like plucking a “surprise” toy from the grab bag bin! We didn’t know what to expect! I’d never heard of the Witch of Endor! And I didn’t have the Book of Job recast as a Pittsburgh sorority sister on my biblical Bingo card, but the brilliant and hilarious Steve Almond sure did! We often say that great writing embodies elements both startling and true, and Elisa Albert’s dead-on comparison of Instagram to the golden calf, and Max Gross’ fashioning Haman in the petty body of a suburban New Jersey rabbi nailed those notes. Michael David Lukas’ generous grappling with fraught questions of legacy, identity, possibility, and inheritance, gifted us with the perfect ending we didn’t know we needed.

Left to right: Sara Lippmann and Seth Rogoff

SZ: Additionally, the power of naming and creation seem to go hand in hand. In this collection, we see characters take on names or leave them behind, just as selves are shed or molded. How do you see naming operating here, especially when it is outside the conventional telling of God doing so?

SL: From an editorial standpoint, it was wild to see so many contributors naturally gravitating to the theme of naming and its implicit/explicit power. True to our project, there is no uniform consensus. Erika Dreifus’s decision to preserve Jepthah’s daughter anonymity infused it with a quiet, subversive power, underscored by the haunting, unnamed choral female point-of-view. By contrast, Ilana Masad, in her erotic translation of the book of Ruth, ascribed deeper, double meaning to the central players by presenting Ruth as Root and Naomi as Pleasantly. Meanwhile, in retelling the story of Dinah, Sarah Blake chooses to underscore the inequity of power – and to rectify the fact that Dinah’s name receives only passing mention – by replacing the stated name of her rapist, Shechem, with Dinah Dinah Dinah to furious effect.

SZ: What are you reading and writing now?

SR: I just finished Tomáš Zmeškal’s Love Letter in Cuneiform for an evening with the novel’s translator Alex Zucker in Prague. I’d recommend an excerpt from Zmeškal’s autobiographical Socrates at the Equator about his search for his Congolese father and the lack of biblical stories of father’s abandoning sons. I’m trying to write three books at once now, which is driving me a little crazy. If I seem crazy in this interview, it’s probably at least partly because of this. One book is a novel about the politics of historical interpretation. It started out as a kind of parody, but sadly the context of the current assault on historical knowledge and practice has transformed it into more of a tragedy, or maybe a eulogy for a vanishing age. In partnership with Ross Benjamin, I have been working on a Kafka-themed substack called FRANZ. I have a new story there called “The Fist,” which is a retelling of Kafka’s retelling of the Tower of Babel story.

SL: In the spirit of creative reading, I’d love to recommend Avner Landes’ astonishing new novel, The Delegation. While on the surface it tells the story of two Soviet Jewish artists sent to the United States during World War II by Stalin to rally support for his party, it brilliantly upends narrative convention by weaving three different, dynamic story lines as well as fact and fiction and metafiction in a mind-blowing, hilarious, and devastating choose-your-own adventure that embodies radical literature at its core. As for writing, I am currently in the production stages for a chapbook of three Jewish stories, and a new novel, Hidden River, due out in May 2026. Beyond that, I’ll share that this anthology continues to nourish in surprising ways, as I just may be in the early stages of a new novel extremely loosely inspired by the classic triangle of envy: Rachel, Leah, and Jacob set in the world of 1990s magazine culture, as that story is another one that hasn’t yet been smashed to bits in our pages.

Simona is the Jewish Book Council’s manager of digital content strategy. She graduated from Sarah Lawrence College with a concentration in English and History and studied abroad in India and England. Prior to the JBC she worked at Oxford University Press. Her writing has been featured in Lilith, The Normal School, Digging through the Fat, and other publications. She holds an MFA in fiction from The New School.