Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

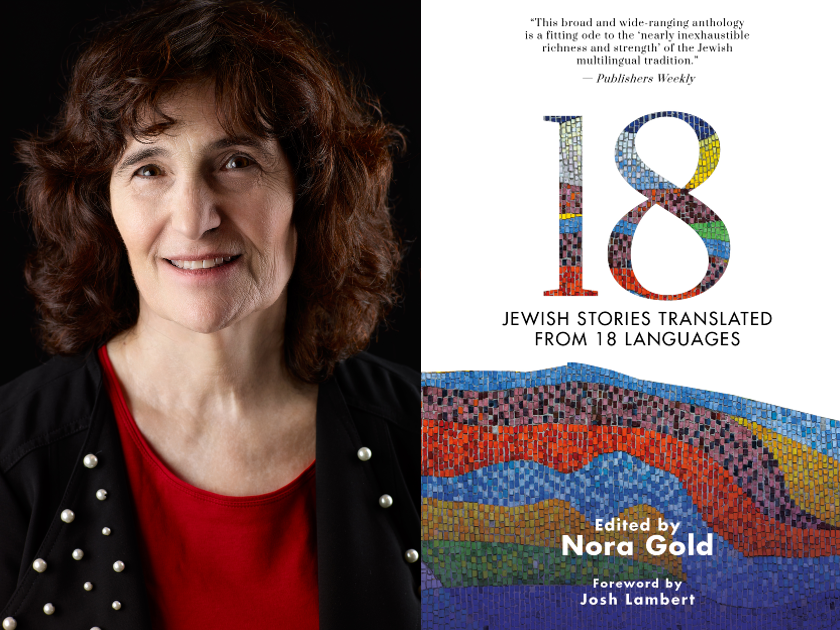

Author photo by Yaal Herman

Simona Zaretsky speaks with Nora Gold on her anthology 18: Jewish Stories Translated from 18 Languages, discussing Gold’s Jewish Fiction .net, translation, and the mulitlingualism of Jewish fiction itself.

Simona Zaretsky: Jewish Fiction .net is now in its thirteenth year and has published over 500 pieces, that is incredible – what was your impetus for starting this journal?

Nora Gold: This may sound strange because digital publishing is now such a normal part of our lives, but when it began, it caused shock waves in the publishing industry. Publishers, suddenly afraid of going under, became reluctant to take on new authors, especially those they considered “niche,” such as writers of Jewish-themed fiction. Back then, I knew several talented writers of Jewish fiction who, because of the crisis in publishing, could no longer find publishers for their work, and I didn’t want all this fine literature to get lost. So I started Jewish Fiction .net, which was then, and still is, the only English-language journal (either print or online) devoted exclusively to Jewish fiction. From the outset, we published stories by both emerging writers and well-established ones, and we welcomed fiction either written in English or translated into English but never before published in English. All of us were, and still are, volunteers. At present, almost a third of the stories in Jewish Fiction .net are translated works, and we have readers in 140 countries.

SZ: How do you decide what a Jewish piece is for your journal? What draws you to a story?

NG: There are many definitions of Jewish fiction, and although this issue has been extensively written about and debated over, a consensus has never been reached. The definition of Jewish fiction that I consider most comprehensive and persuasive is Ruth Wisse’s in The Modern Jewish Canon. Wisse’s definition, like any, has its limitations, but I agree with her assertion that a Jewish story is one that is “centrally Jewish” (a phrase originally coined by Cynthia Ozick that Wisse borrows). To Wisse, “centrally Jewish” means reflective in some way of Jewish experience, Jewish consciousness, or the Jewish condition. Of course, what it means for a work of fiction to reflect Jewish experience, Jewish consciousness, or the Jewish condition can be complex to define. To me, a story that is Jewish expresses Jewish identity on either a religious or cultural dimension, and it relates in a fundamental way to Jewish experience, whether in the past, present, or future. In this kind of story, the Jewish content is inextricable. Unlike stories that purport to be Jewish literature simply because they contain a bagel or a character with a Jewish name, with authentic Jewish fiction you can’t extract the Jewish element of the work and still leave the story standing.

An additional aspect of Wisse’s definition is that in Jewish fiction, “the authors or characters know, and let the reader know, that they are Jews.” There is a choice offered here between author and character, and to me this means that it is sufficient for the character in a story to fulfill this role. It need not be the author, and therefore the author need not be Jewish. Over the years I have encountered, and published, some first-rate Jewish-themed fiction written by non-Jews, and an excellent example of this is in my book 18 with the novel excerpt “Golem,” translated from Polish.

You ask what draws me to a story. For me, a story has to feel alive. It can have an internal focus, an external focus, or a mix of the two, but it needs to move (in the sense of forward movement) and it needs to move me. I also love wordplay; rich, allusive use of language; and language that is stretched like an elastic in service of the story being told, not in order to show off.

SZ: 18 is such a wide-ranging collection of stories, from the language they are written in, to the settings, stories, and characters themselves. How did you choose eighteen stories from the wealth of pieces you’ve published online?

NG: In a few cases, choosing which story to include was easy because we had published in Jewish Fiction .net only one story translated from that language. Mostly, though, this decision was challenging because we had published so many works translated from a particular language, all of them excellent, and we could pick only one. For instance, we had dozens of translations from Hebrew to choose from. When making my selections for this anthology, I considered a number of variables, such as the desirability of including at least a few authors whose names would be familiar to English-language readers. But ultimately I picked eighteen stories that I loved.

SZ: In the introduction, you mention that translation and international reach is extremely important to the overall tapestry of the collection as well as your own approach to the work you publish in your journal. Could you speak on this?

NG: I always conceived of Jewish Fiction .net as an international journal that publishes translated works, but it took several years of doing this before I fully grasped its significance. By then I’d heard from many of our readers whose first language was English that until discovering Jewish Fiction .net, they’d never encountered Jewish fiction in translation (other than, perhaps, stories translated from Hebrew, Yiddish, or Ladino). Many people whose first language is English hear the phrase “Jewish fiction” and think only of Jewish fiction written in English, and generally only American Jewish fiction – not Canadian, British, Australian, or South African, much less what’s been written in other languages. This is both unfortunate and ironic because – related to Jews having lived for two thousand years among other nations and writing stories in those nations’ languages – one of the key features of Jewish fiction is its multilingualism. Identifying this gap in knowledge among my readership at Jewish Fiction .net is what prompted me to create 18.

Finding the translated works for Jewish Fiction .net is not always easy. Sometimes these stories just show up in our submissions portal; other times an author, translator, or publisher writes to me asking if I’ll consider a piece of their work. Usually, though, I have to hunt for these stories myself. The challenge in doing this is that I’m always looking for fiction that has already been translated into English but not yet published in English, and when this involves a book — a novel or story collection — there is only a small window between the time that a translation is completed and when the English-language book comes out. Publishers love Jewish Fiction .net because we provide their books with free worldwide publicity, but the only way to access these works at exactly the right moment is by knowing the author, translator, or publisher, and arranging all this well in advance. For this, an extensive international network is crucial, and I am fortunate in having developed one over the past thirteen years. Still, each new language that I begin to explore is its own world with its own unique network, so I have to start from scratch, seeking someone who might know someone, who might know someone, etc. It’s a lot of work but it’s also fun, and I’ve met some wonderful people along the way.

And please, if you are reading this and have some contacts to suggest or ideas to share, get in touch with me. I am always on the lookout for translations from languages we have not yet published, as well as new translations from the twenty languages we’ve published so far.

I always conceived of Jewish Fiction .net as an international journal that publishes translated works, but it took several years of doing this before I fully grasped its significance.

SZ: In looking back over more than a decade of stories and creating this collection, are there elements or themes within stories that remain constant?

NG: There are. In addition to all the universal themes you’d find in any collection of stories, like love, there are certain Jewish-relevant themes that span 18 and Jewish Fiction .net. These include: the Jewish family; antisemitism; morality and immorality; outsider identity; relationships (both positive and negative) with non-Jews; the Holocaust; pride in, and love of, Jewish tradition; and critique of this tradition and of the Jewish community (for example, due to its sexism).

There have also been some interesting and idiosyncratic patterns in the submissions we’ve received at Jewish Fiction .net. A surprisingly high number of submissions involving the Holocaust (stories written not only by older authors, but younger ones, including teens), and golems. Also, in the first couple of years of Jewish Fiction .net, we received six submissions of stories (of which we published only one) where a young woman committed suicide in a mikveh. This was so startling that I wrote an article about it, which was published in The Forward. In recent years, we have not received any stories on this theme.

SZ: Was there anything surprising that you came across while revisiting the stories in 18?

NG: Yes. 18 was published and had its book launch on October 17, ten days after the horrible events of October 7. During those ten days I turned to 18 for solace. Rereading it, I was surprised by how relevant the stories in it are to this terrible moment in which we find ourselves. For example, I was stunned to reencounter Elie’s Wiesel’s “Hostage,” which, when I first accepted it for Jewish Fiction .net, seemed quite a far-off setting and situation for a story, yet now has more immediacy and resonance than one would ever want (especially for those of us who know one of the hostages in Gaza). I almost canceled my book launch because it seemed inconceivable to celebrate anything at this time. But then I decided to turn the launch into an event that reflected on the resilience, wisdom, and strength of the Jewish people, as shown in the stories in 18. So that’s what I did. I spoke that night about what a book can and cannot do. 18 cannot rescue hostages, bring the murdered back to life, or heal the horribly wounded. But a book can still offer us something. Hope, meaning, perspective, even solace. That evening ended up being a comfort to me and to everyone there. I was surprised to discover that 18 had the power to do that. And I hope it does the same for everyone who reads it.

SZ: What are you reading and writing now?

NG: These days I’m both reading and writing novellas. I love novellas because they have such power and range, and at the same time such intimacy and conciseness. To me, they embody the best of a novel and the best of a short story. What I read most recently was a novella by Thomas Mann, Chaotic World and Childhood Sorrow, in a new translation from Damion Searls’ book, Thomas Mann: New Selected Stories. It’s an extraordinary translation, which, after reading Mann all my life, makes me feel like only now have I met the real Thomas Mann. Such is the power of a great translation.

Regarding my own writing: In just four months, on March 1, I have a book of two novellas coming out—Yom Kippur in a Gym and In Sickness and In Health. In Yom Kippur in a Gym, five random strangers at a Yom Kippur service in a gym are each struggling with an intense personal crisis, when a medical emergency unexpectedly throws them together, and in one hour all their lives are changed in ways they would never have believed possible. In Sickness and In Health is about a woman who had epilepsy as a child so her most cherished goal has always been to be “normal”; but just when things are going right for her (with her family, friends, and artistic career), some cartoons she drew threaten to reveal her secret medical past and destroy the life she’s worked so hard to build.

Two years later, in 2026, another of my novellas will be published. Doubles, set in 1968 in an institution for troubled youth, is told from the perspective of a brilliant, spunky, twelve-year-old girl who is obsessed with math.

And guess what I am writing now? Another novella (of course)! I am on a novella roll.

Simona is the Jewish Book Council’s manager of digital content strategy. She graduated from Sarah Lawrence College with a concentration in English and History and studied abroad in India and England. Prior to the JBC she worked at Oxford University Press. Her writing has been featured in Lilith, The Normal School, Digging through the Fat, and other publications. She holds an MFA in fiction from The New School.