Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

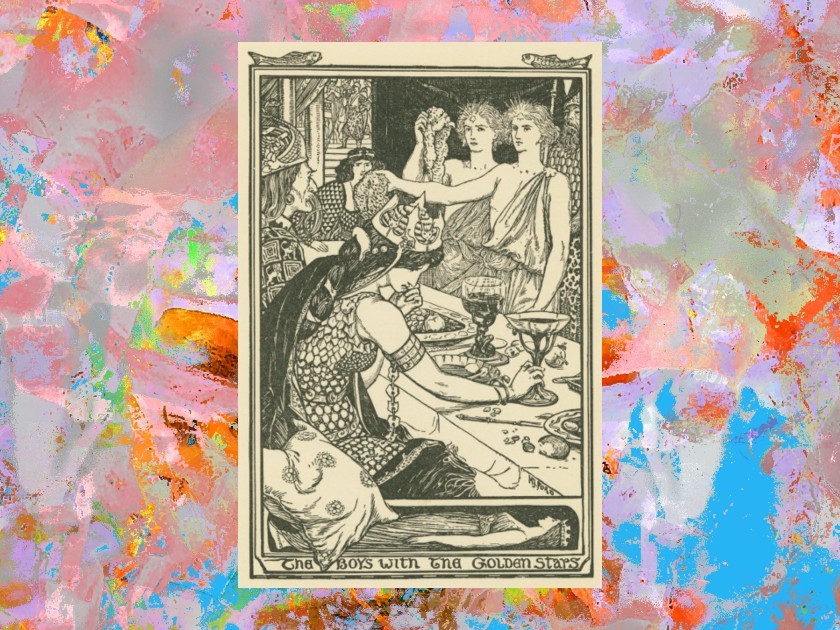

“The Boys with the Golden Stars,” by H. J. Ford, in Andrew Lang’s The Violet Fairy, 1901

New York Public Library, Digital Collections

I had two things in mind when I first set out to write The Light of the Midnight Stars: I wanted to retell the Romanian fairy tale “Boys With Golden Stars” — which my mother read to me as a child — and to find out why my grandmother lit Shabbat candles in a closet.

I never saw my grandmother do this, but my father and his sisters all remember it. By the time I came along the candles had moved to the center of the table, and my grandmother’s dementia prevented her from being able to tell us more. But the memory was carried forward.

“Boys With Golden Stars” is the story of three sisters who each pledge to do a different magical thing if the emperor agrees to marry them, and the youngest among them pledges that she will give birth to twin baby boys with golden stars on their foreheads. For me, this immediately spoke to the idea of hidden Jews — crypto-Jews or conversos. Jews have tried to hide their faith throughout history, only to have it show up in unexpected ways. At the outset, I expected to find a skeleton in my family’s closet from Spain or Portugal — the place I most associated with stories about hidden Jews. What I found was perhaps more chilling.

My grandmother was from Romania, but before her family moved to Romania they lived in Hungary — what is today’s Slovakia. The Jews from thirteenth and fourteenth century Hungary were made to wear badges (not golden stars) and were expelled from Upper Hungary (now Slovakia). This included the community of Rabbi Moses Sofer, the Hatam Sofer, of whom my grandmother was a descendent.

Some went to Austria, some to Wallachia, others returned to Hungary (present day Slovakia) only to be expelled again. The story of the Jews in this region is the story of expulsion and return. What is clear is that the Spanish and Portuguese Jews fleeing Inquisition Spain were not the only ones who were forced to light candles in closets. There are stories from across Eastern Europe, Ukraine, Russia, Italy, Morocco, Iran, India, Mexico, Peru, Bolivia, Columbia, Cuba, Jamaica, and even Arizona about Jews who hid various practices in fear of discovery.

The Light of the Midnight Stars is not a story that has a happy ending. It tells the tale of the very real Rabbi Isaac of Trnava, his three daughters, and his family’s magical legacy. Rabbi Isaac is said to have come from the same region my grandmother’s family was from. He wrote the Book of Customs (Sefer HaMinhagim) upon which I based parts of my Book of the Solomonars. His three daughters are Solomonars — magic users who get their powers directly from the line of King Solomon himself (much like a Cohen or Levi today might trace their lineage back thousands of years).

Where our ancestors came from is as much a part of who we are today as the place where we were born. It’s a legacy we all carry in our bones. A story we tell and retell every year.

The Solomonars are also a myth from this era — red-haired wizards who rode cloud dragons in the skies. They were a kind of antisemitic trope — mountain men and women descended from Khazars, or Red Jews, and said to control the weather. Like the goblins in my first book, The Sisters of the Winter Wood, it was an antisemitic trope that I wanted to turn on its head and reclaim as a part of my story and a part of a larger Jewish narrative. Ultimately, The Light of the Midnight Stars is a story about finding faith in the darkness. It is specifically about the times of the Black Plague in Europe — which many communities of Jews were blamed for, and so expelled.

As Jews, we are by nature storytellers. The Torah itself is a story — one in which we are commanded to tell our story and to tell it to our children. Nowhere is this more apparent than during the holiday of Passover. In the Passover Seder, Rabbi Gamliel says: “In each and every generation, a person is obligated to see himself as if he himself left Egypt.” I would like to propose that this applies to other forms of Exodus as well — expulsion.

Where our ancestors came from is as much a part of who we are today as the place where we were born. It’s a legacy we all carry in our bones. A story we tell and retell every year. In Deuteronomy, Moses says, “Remember the days of old; consider the generations long past. Ask your father and he will tell you, your elders, and they will explain to you.”

The stories and traditions that our grandmothers, grandfathers, great-grandmothers, and great-grandfathers passed down have stitched themselves into the fabric of our lives. Where did we come from? Where did we come from before that? And before that?

When did the first golden star appear?

While my story is part-fantasy, it is also a very real look at golden stars that have a way of appearing and disappearing throughout history.

Rena Rossner is a graduate of Johns Hopkins University, Trinity College, Dublin, and McGill University. She is a literary and foreign rights agent, and lives in Israel with her family.