Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

Star of David, Photo by Alex Proimos via WikiMedia Commons

My grandparents spoke little of their wartime experiences and all they lost. But they spoke proudly, and often, of the life they built afterwards in their haven — Australia. Sometimes we would ask our grandparents, “Why Australia?” Their answer was always the same: “We wanted to get as far away as possible from Europe.” They couldn’t have gone further than the place deemed “the edge of the diaspora,” by Jewish Australian historian Suzanne Rutland.

After World War II, Australia became home to the largest group of Holocaust survivors (per capita) outside of Israel. They flourished, joining a small, predominantly Anglo-Jewish community, some of whom arrived as convicts on the First Fleet in the late 1700s. In the second half of the twentieth century, exiles would arrive from the former USSR, followed by large waves of migration from South Africa and Israel.

Australian Jewry is markedly distinct from US Jewry, whose larger Jewish population allows for greater diversity in practice and politics. The Australian Jewish community is much smaller and notably more cohesive and traditionally oriented, shaped by Holocaust memory and our geographical concentration in Australia’s major cities — Sydney and Melbourne (with much smaller communities around the country). We have always been considered a vital diaspora community. As a whole, we are firmly committed to Israel, and diverse but united across denominations. We have the highest Jewish day school enrolment rates across the diaspora, a vibrant cultural life, and marked contributions to broader Australian society across sectors.

Many other migrant and refugee groups have found their way to Australia over time, and our national multicultural project has been a source of pride — though not without challenge — and one that felt safe and meaningful for many Australian Jews. This is not to say that Australian society has always been kind to migrants and refugees, nor that antisemitism hasn’t reared its ugly head. What has been a better understood phenomenon, namely far-right antisemitism — active but socially marginal — has now been joined by far-left antisemitism — often displayed as anti-Zionism — and pockets of Islamist radicalisation.

My grandparents spoke little of their wartime experiences and all they lost. But they spoke proudly, and often, of the life they built afterwards in their haven — Australia.

Despite its geographical distance from Israel, Australia was not spared the tsunami of hate that engulfed Jewish communities in the wake of October 7. Perhaps because of our small population (25 million, of which only approximately 120,000 identify as Jewish) and our historically firm sense of belonging in Australia, the upending of our haven has been deeply felt. The silence of our peers and neighbours was piercing. These past two years, we have been blindsided by the lack of government response to the rise of hatred especially in cultural and institutional spaces, anti-Jewish harassment including vandalizing sprees, and firebombings.

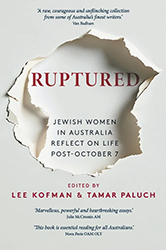

The lived experience of these times was captured in a book of personal essays Ruptured: Jewish Women in Australia Reflect on Life Post-October 7, coedited by myself and Lee Kofman. Ruptured was a creative response to the grief and trauma we were experiencing as our sense of safety and belonging unravelled. The book preserves history as it unfolds and seeks to foster empathy in the present. It also carried warnings of what could come if our voices were not heard.

By the time the hate exploded on Bondi Beach last month, murdering fifteen people (including three non-Jewish Australians), and traumatising scores of others, so did our community’s anger at being ignored when everything we warned would happen did. But something else shattered that day. The silence. Australians were stunned that words could become violence, that their magnificent shores could be desecrated with blood. This has restored some confidence for the Jews of Australia, but also raised the question — why did the writing on the wall need to turn bloody for action to be taken?

Many Jewish Australians will tell you how grateful they are that their parents and grandparents are not here to witness what has unfolded these past two years. But Alexander Kleytman, a Holocaust survivor and the oldest victim of the Bondi Massacre, was present and lost his life on the beach that day. Like my grandparents, he too sought “the edge of the diaspora” as sanctuary. Time will tell if the future that his grandchildren inherit breaks the cycle of antisemitic violence that he was not fated to escape.

Ruptured: Jewish Women in Australia Reflect on Life Post-October 7 by Lee Kofman and Tamar Paluch

Tamar Paluch trained as an occupational therapist, with a focus on disability rights and community development. After October 7, she co-founded a platform to document women’s experiences of these times. Ruptured is a culmination of her community activism and long-held passion for writing, especially on matters of grief, identity and memory.