Books on the 1964 Mississippi Freedom Summer are classified under African American history and civil rights. But the project was rife with Jewish participation.

Books on the 1964 Mississippi Freedom Summer are classified under African American history and civil rights. But the project was rife with Jewish participation.

Organizations from the civil rights movement including the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC, pronounced “snick”) and the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) led the voter registration and education campaign. We mark the 50th anniversary this summer. The actual event went well beyond the best-known names — New Yorkers Michael Schwerner and Andrew Goodman with Mississippian James Chaney. They were the civil rights workers who went missing in the first days of the project and who later were found brutally murdered by local law enforcement connected to the local Klan.

A number of books recount the complex organization that went into the massive voter registration drives and educational efforts that set up Freedom Schools in the state with the reputation for being the most racist and brutal. There were an estimated 650 volunteers, mostly Northerners, mostly white, and mostly students.

Reading these stories links the Jewish American narrative to the African American efforts to stamp out discrimination. Many of these long unsung heroes for democracy and diversity were inspired by the injustice of the Holocaust. The civil rights workers and the summer volunteers challenged the roadblocks set up by the state of Mississippi to keep Blacks from voting, getting a decent education, and holding elected offices.

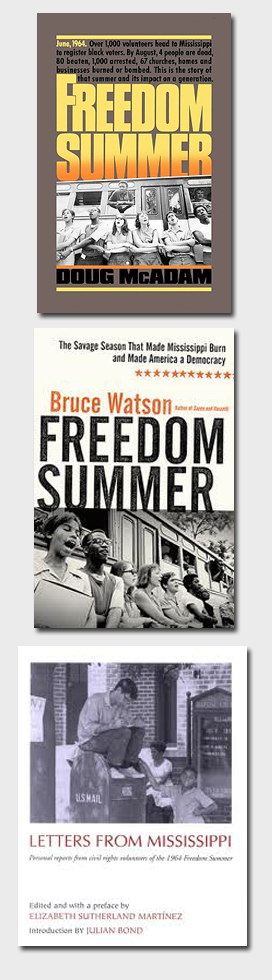

Freedom Summer by academic Doug McAdam (Oxford University Press, 1988) traces the chronology of events with voices from the Freedom Summer volunteers themselves. McAdam conducted numerous additional surveys and interviews with volunteers. He traced the origins of the project from the search for volunteers, the unique and jarring training, through the immediate impact of Freedom Summer. He delves into the lessons of Mississippi with the participants, finding out how the volunteers and society were impacted through the 1970s.

Back in 1964, organizers used a WATS line in the Magnolia State to document the violence and organize movements.

They logged:

4 project workers killed

4 persons critically wounded

80 workers beaten

1000 arrests

37 churches bombed or burned

30 black homes or businesses bombed or burned

An epic read, McAdam’s photographic inserts documenting the events include images of sweaty young women teaching Mississippians in rudimentary Freedom Schools and young male college students organizing voter registration drives. I was riveted by the photograph of the young, whippet-thin widow Rita Schwerner, who told the second group of Freedom Summer participants training in Ohio that her husband’s disappearance only made it more important that the project go forward.

Bruce Watson’s 2010 book Freedom Summer: The Savage Season That Made Mississippi Burn and Made America a Democracy (Viking) is a powerful narrative. Watson links Freedom Summer’s impact to the twenty-first century and the election of the first black president. It is rooted in the African-American victims and heroes including Freedom Summer organizer Bob Moses.

Watson is direct about the controversial nature of Freedom Summer. He wrote that SNCC “had braved Mississippi when no one else would. They still bore the scars — bloody welts, broken bones, bullet wounds you could put your finger in. And now a bunch of white college kids with names like Pam and Geoff were being invited to Mississippi to gather headlines and plaudits for bravery.”

Their names also included: Jacob Blum, Paul Cowen, Bob Feinglass, Barney Frank, Adam Klein, Ruth Koenig, Rita Koplowitz, Robert Mandel, Sara Lieber, Betty Levy, Mark Levy, Michael Lipsky, Judy Michelowsky, Ira Landess, Mendy Samstein, Nancy Samstein, Peter Rabinowitz, Gretchen Schwartz, and Ellen Siegel.

Watson’s descriptive writing captures the often pampered participants’ youthful idealism, their elation connecting with black Mississippians, especially the intellectual hunger and the palpable fear. Watson’s research on the Schwerners and Andrew Goodman and his family paints a picture of their passion for civil rights.

In the center photo-spread of a volunteer bathing next to a hand pump, a student engaging in door-to-door voter registration, and an idealistic teacher with her students’ work is an image of Rabbi Arthur Lelyveld beaten and bloody on a voter registration foray in Hattiesburg.

Letters from Mississippi by Elizabeth Sutherland Martinez, published by McGraw Hill in 1965, is full of the raw emotion and feelings the participants expressed to their parents and friends as the events were unfolding. You can feel the exhilaration, fear, heat, and mosquitos. The book has a quilt-like quality utilizing the actual words of the volunteers. “Batesville welcomed us triumphantly — at least Black Batesville did….. Sometimes when we pass by, the children cheer.”

The book follows the characters fighting their battles with violent rednecks, the heat, and poverty. There are also victories. One Freedom School teacher wrote: “The atmosphere in class is unbelievable….They are excited about learning. They drain me of everything that I have to offer so that I go home at night completely exhausted and happy.”

Readers may come away deflated, like the participants themselves as they left the Magnolia State. The Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party was not seated on the floor of the Democratic National Convention and racism did not disappear after 1964.

These books are a window into the strength of inter-racial coalitions of the early-1960s and the idealists who participated.

If you’re interested in finding out more about the Freedom Summer, check out the events and locations for the traveling exhibit “A Freedom Summer Exhibit for Students from the Wisconsin Historical Society,” here.

Dina Weinstein is a Miami, Florida-based journalist currently researching Jews in St. Augustine, Florida during the 1960s era civil rights struggle there with a grant from the Southern Jewish Historical Society. She mentors young journalists as an adviser at the Miami Dade College student newspaper The Reporter. Weinstein has taught journalism and mass communications at a number of colleges including Miami Dade College. She is a Boston native and a graduate of Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism and Boston University School for the Arts.

Related Content:

- There’s Something About Moses by Mary Glickman

- Troubling the Waters: Black-Jewish Relations in the American Century by Cheryl Lynn Greenberg

- Hot Pursuit: Murder in Mississippi by Stacia Deutsch and illustrated by Craig Orback

Dina Weinstein is a Richmond, Virginia-based writer.