Join a community of readers who are committed to Jewish stories

Sign up for JBC’s Nu Reads, a curated selection of Jewish books delivered straight to your door!

Earlier this week, author Gavriel Savit introduced the spiritual mysticism contained in uncertainty and pondered the corporeal existence of God. With the publication of his debut novel, Anna and the Swallow Man, Gavriel is blogging here all week as part of the Visiting Scribe series on The ProsenPeople.

Quite a while ago, my fiancée and I decided to undertake the systematic reading and study of what Western tradition refers to, absurdly (if in Greek), as THE BOOK. I had never before come to the Bible in a systematic and sustained way, reading from cover to cover, and as someone with the humble ambition of contributing to the wild, out-of-hand fracas of Western narrative art, I felt it would be in my best interest to have a bit of a cultivated familiarity with the great patriarch of that art. My fiancée, a critic and scholar of Victorian era British literature, thought it would be in her best interest to have a similar familiarity with the cornerstone of its great patriarchy.

And so we were well matched. The only problem was methodological. I, coming from a Judaic background, wanted to work on the khevruta model, reading together out loud and entering into discussion whenever something interested or troubled one of us; she, well used to the silent if disorderly decorum of the library carrel, would have preferred to read silently in parallel and then to come together for discussion after the fact. In general, I can see the appeal of this approach — it must be nice to thoroughly formulate one’s opinions before beginning the process of discussion — but the fact of the matter is that the Hebrew Bible seems explicitly designed to frustrate certainty. For a book that has so commonly been appealed to for definitive answers, it hardly seems to contain any, from a narrative perspective. No, no — no certainties to be found here, only competing, incommensurate, equivalid alternatives. It has to be discussed as it’s read.

No, no — no certainties to be found here, only competing, incommensurate, equivalid alternatives. It has to be discussed as it’s read.

The Book begins with two successive, irreconcilable accounts of the creation of the universe: in the first, God creates life in general, both flora and fauna, and then, only after this does God create the human being, presenting to it in all its bounty the comestible world of fruit and vegetable. Less than ten verses later, in the second account, the creation of man is related again, this time expressly predating the emergence of vegetal life. Shortly thereafter, the creation of animals will also be found, in this second account, to come after the creation of human life.

There’s nothing for it. There’s no way to reconcile the two expressly and exclusively different stories.

If you are a contemporary rationalist, this might well prove your disdain for the archaic, superstitious tome of falsehoods known as the Bible. How can it equally assert the veracity of two contradictory accounts?

If you are a philologist, you will likely interpret this conflict between texts as indicative of the presence of more than one pre-existing source. Neither, of course, could be altered in the combination because of the sacred status of each, and neither, by the same token could be excluded. As a philologist, one might easily say “Forget the cognitive dissonance, forget the conflict, forget the juxtaposition. Read each on its own merits.”

If you are an adherent of rabbinic exegesis, perhaps you will choose to interpret these two pieces of narrative as predominantly allegorical or symbolic writing. After all, when we adjourn to the hazy arena of symbolism, we need no longer consider contradiction threatening — it’s, y’know, art.

I would like to offer an alternative reading, one that I hope can extend far beyond this first section of the Hebrew Bible to encompass it entirely:

There are two stories. They are both correct and valid — equally articulated in the authoritative voice of the text. They both take place within a literal realm, and they contradict one another.

There. It’s uncomfortable. It’s difficult. It’s provocative. And I think that’s precisely the point.

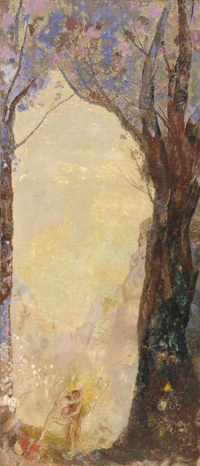

It is in this state of uncertainty that one looks closely, and one sees. You begin to see the face of God in the flickering, dimly lit open space only when you stand between twin certainties — that God has absolutely no visible form, and that God absolutely does.

There’s a reason this gigantic compilation of stories opens on contradiction and uncertainty, and as a writer, I would posit that it’s a lesson in reading the rest of the book: there are two, oppositional positions. Do you smash them together, trying to make them into one? Do you look for ways to discount certain portions of each?

Or do you take one in each hand, and feel them counterbalance one another in the weight of your step?

This mode of reading might be most strongly resisted by those people who point to its essential duality — after all, we are a people of One God, and Singularity, Unity, Oneness presents itself as temptingly contradistinctive. People can so easily say, God is One, and God is mine. If you disagree with me, then God is not yours. My minhag, my family or communal custom in the observance of tradition, one might say, is exclusively correct, and all others are at best to be tolerated, and at worst, heretical. (Looking at you, here, Israeli Rabbinate…)

But this is clearly not reflective of historical Jewish tradition. The Talmud was, in some deeply critical ways, formed in the crucible of the disagreement between the twin philosophical approaches of Hillel and Shammai. Moving backwards, one could easily read an interest in dueling perspectives in the simple notion of the Oral Law, given alongside the Torah on Mount Sinai, for the purposes of elucidation and interpretation — why a separate corpus if not expressly to create distance and discrepancy between the two?

And there are all sorts of incommensurate alternatives in the Bible. David, paragon of majesty, progenitor of Messianic salvation, is, in some very real ways, a usurper of Saul’s kingship. The theme of rival claims is threaded throughout the Bible, particularly in the foundational stories of our patriarchs.

After all, who deserves primacy? Ishmael, the firstborn, or Isaac, the legitimate? The supremacy of the elder son, so axiomatic in the Ancient world, will continue to inform and enlarge the successive stories of each great patriarch — mainly in its violation. Jacob, the wily (younger), or Esau, the mighty (elder)? Joseph, the brilliant (far, far younger) or Reuben the dutiful (eldest) and his corporate brotherhood? Aaron, the priest (elder) or Moses, the leader (younger)?

In none of these cases — looking carefully, honestly — is one party clearly the preferable. It is, particularly from an antiquated perspective, always unclear.

And perhaps this is obvious. After all, we as Jews are known in the collective as the Children of Israel, Israel (“Struggles-with-God”) being the alternative name given to Jacob after he strove and fought all night against an agent of God — crucially, to an indecisive conclusion.

And perhaps this is obvious. After all, we as Jews are known in the collective as the Children of Israel, Israel (“Struggles-with-God”) being the alternative name given to Jacob after he strove and fought all night against an agent of God — crucially, to an indecisive conclusion.

Neither God nor Israel prevailed. This was not the point. The struggle was the point.

The renaming of Jacob in the wake of this conflict is well-known and oft-quoted. What is less frequently repeated is that something else was renamed in the wake of the conflict: the open space in which Jacob and the Agent of God struggled.

The place was named Peniel, or “My-face-is-God.”

It is, of course, indispensable to have two well-matched and equally viable candidates in order to enter into the sort of furious, infinite, ongoing, and indecisive conflict that our narrative tradition so favors. Just as indispensable as the conflicting parties, though, is the arena in which the contest is to take place.

And this, finally, is the utility, the virtue of uncertainty.

A certainty is an insuperable obstacle. It’s solid and heavy and doesn’t move much of its own accord. Certainties, of course, have great utility of their own — they can block off dangers, you can climb up atop them, reaching for new intellectual altitudes — but if you’re looking to stage a fight, it’s hard to do so inside a block of marble.

I, like many young Jews, once visited Israel on a Birthright trip, and the entire thrust of Jewish thought and history was never so legible to me as the time we were encouraged to go off into the midnight desert for a little, quiet, solo reflection — not so far that we couldn’t still see the lights of the tent, but far enough that we could imagine we couldn’t.

The sky is so big, out there, and so full of stars. Unified and simultaneously multifarious — monotheism doesn’t seem like an innovation in the desert, it feels like an observation.

Because these are the uncertain spaces, the open (empty?) arenas in which we Jews are used to seeking for (and finding, hopefully) our God: the desert, monolith of sandgrains; the synagogue, light flickering, prayer shawls flapping, eyes covered to ward off blindness; the genealogy of our Fathers, so knotted and ambiguous that even a family tree is nothing so much as an argument.

These are our plains of Peniel, mottled and dappled by striving footprints, by wingtips dragging through the sand.  This is the Face of God: the constant contest of uncertainties in an arena uncrowded by decision, unmarred by conclusion. The endlessly repeated gesture of young men peeking out from behind their father’s prayer shawls, of elders squinting through their glasses across the dimly lit space, generation after generation, of looking so closely that you start to see something in the struggle and bump, in the flicker and flash, in the dim and shade — a Single, emergent Entity.

This is the Face of God: the constant contest of uncertainties in an arena uncrowded by decision, unmarred by conclusion. The endlessly repeated gesture of young men peeking out from behind their father’s prayer shawls, of elders squinting through their glasses across the dimly lit space, generation after generation, of looking so closely that you start to see something in the struggle and bump, in the flicker and flash, in the dim and shade — a Single, emergent Entity.

Just don’t you dare become certain what it looks like.

Gavriel Savit is an actor and author from Ann Arbor, MI, and a graduate of the University of Michigan’s prestigious Musical Theatre program. He is the author of Anna and the Swallow Man (Knopf, 2016) and an emerging voice in Jewish literature.

Related Content:

Gavriel Savit holds a BFA in musical theater from the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, where he grew up. As an actor and singer, Gavriel has performed in three continents, from New York to Brussels to Tokyo. He is also the author of Anna and the Swallow Man, which The New York Times called “a splendid debut.”