By now, it is commonplace, nearly reflexive, to say that art produced by targets of the Holocaust testifies to the dignity of the human spirit. Indeed, similar sentiments are expressed in some of the essays that preface the excellent Art from the Holocaust: 100 Artworks from the Yad Vashem Collection. The artwork itself provides an opportunity to refine and clarify that statement.

These hundred paintings and drawings, expertly chosen from the vast collection of Yad Vashem, represent a sample of the output produced by residents of the ghettos, work camps, and death camps. Approximately half of the artists featured did not survive.

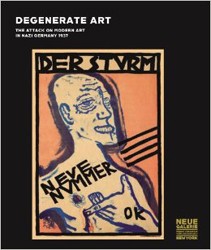

We may be astonished to find that the Holocaust scarcely registers in these pieces. Certainly it dominates the subject matter, but when considering the work as art, the viewer could be looking at a survey from the period devoted to any theme. The artists can be roughly divided into naïve and professional categories. The naïve make the pictures that naïve artists make: clumsy and sincere depictions of what lies before them. The image is deformed, but what is intended is clear. The professional artists, by contrast, precisely reflect the state of the artistic discourse at the time the art was made. We see both work that is nostalgic for the realist traditions of the nineteenth century and work that is influenced by different strains of the modernist project. Some artists turn to sentimentality akin to Chagall’s, others to the sulfurous comedy of a Kokoschka-like outlook or to Matisse’s lyrical minimalism, and still others to the satirical line drawing styles common in central Europe in the 1930s. Traces of Cezanne, Picasso, Fechin, Kollwitz, Schiele, and Lada abound — not because the artists mimic them, but because these stylistic and thematic tropes were in the air.

One might expect the artists to slavishly record the details, to provide testimony so that this monstrous interval should never be forgotten. And indeed, at the level of narrative and content, the artists seek to do that. But they largely fail to develop the utilitarian eyes of war illustrators or courtroom sketch artists. Even in the midst of the blackest night, these artists cannot stop functioning as artists. Their subject a given, they spend their narrow time and material resources refining their styles, working on contemporary problems in aesthetics, and parsing their environments for exciting artistic opportunities.

This is perhaps the real triumph of the human spirit: not to go on making art in the face of the abyss, but to go on making art that is part and parcel of the artistic discourse. It declines to be defined by the crucible of its creation. It refuses to be impoverished by its circumstance or to become alienated from beauty and joy. It testifies to the persistence of an ordinary vivacity, up to and beyond the bitter end. It is a credit to the Jewish people, and, one hopes, humanity at large.

The book includes several forwards and essays, and clear, helpful notes on each image and its maker.

Related Content: