Birthright is Erika Dreifus’s first book of poetry, but it is preceded by her prize-winning short story collection, Quiet Americans. The poems in Birthright often feel like stories in miniature, replete with setting, character, dialogue, and plot, across a wide variety of registers and contexts, ranging from biblical to personal, familiar to historical, literary to political. Poems that draw from biblical stories are interspersed with personal stories, which productively complicates both types of poems. “The Autumn of H1N1,” which critiques medical and social attitudes toward women who have chosen not to have children, appears beside “Ruth’s Regret,” whose title character laments, “No one said that milk would leak from me / while my baby nestled at Naomi’s breasts.” The contrast between the settings and speakers of these two poems adds rich texture to both.

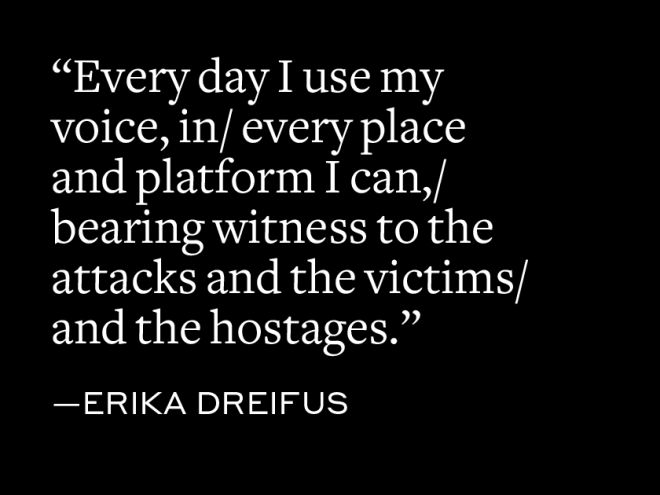

Dreifus’s fiction-writing sensibility is both a strength and a weakness in Birthright. Sometimes, the use of conversational language feels fresh, like in “Kaddish for My Uterus,” which plays with moments of humor, undermining the formal expectation its title sets up. “This Woman’s Prayer” expresses gratitude to be born “in the last third of the twentieth century, / a time after penicillin / and before social media.” These are joyful, complex, mournful, lovely prayers — fit for the twenty-first century. At other times, Dreifus’s casual language can feel prosaic. Parts of “Diaspora: A Prose Poems,” sound more like an email than a poem: “I wait for my plane to Columbus, Ohio, where the elder daughter of a second cousin will be called to the Torah as a bat mitzvah in the morning.” That prosaic tendency is also evident in three poems inspired by iconic twentieth-century poems: Lucille Clifton’s “Homage to My Hips,” which becomes “Homage to My Skull”; Auden’s “September 1, 1939,” which becomes “September 1, 1946,” and, after Wallace Stevens, “Thirteen Ways of Looking at My Latest Cold.” The original versions of each of these poems work thrillingly with form, line breaks, sound, and tone. In comparison, Dreifus’s poems seem less exciting, because they don’t engage poetic tools as thoroughly.

My favorite poem in the book is the final one titled, “With or Without,” a prose poem that takes full advantage of some of the opportunities that poetry offers: freedom from grammatical constraint and close attention to pattern, repetition, and sound. Dreifus’s delightful tendency to mix registers is evident in this poem, which begins with a chant-like directive: “Come with me sit with me stay with me play with me lie with me with all your heart…” and touches on many of the concerns Birthright explores, like politics, geography, personal and familiar history, and sensory experience. Dreifus writes, “with tears without stopping with a smile with a laugh with finished basement with washer/dryer with skylights with bath with salt with fries with dressing on the side with cheese with tax with fees with honors with distinction…” This poem’s wonderful mishmash of registers shows Dreifus at her most powerfully resonant.

Lucy Biederman is an assistant professor of creative writing at Heidelberg University in Tiffin, Ohio. Her first book, The Walmart Book of the Dead, won the 2017 Vine Leaves Press Vignette Award.