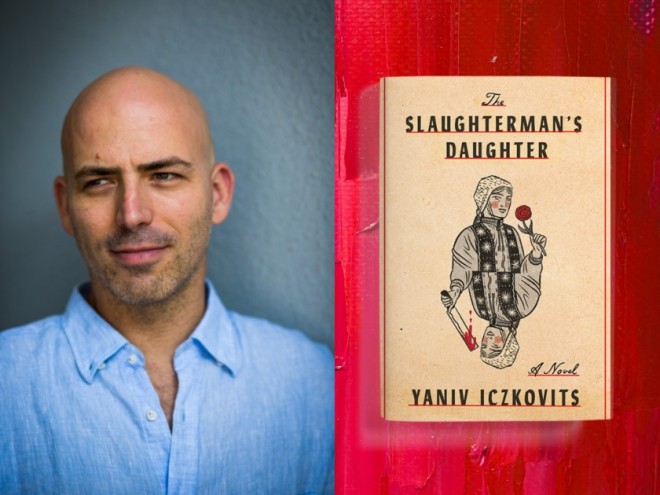

The Slaughterman’s Daughter, Israeli author Yaniv Iczkovits’s third novel and first to be translated into English, takes place at the tail end of the nineteenth century in the Pale of Settlement. The population of the town of Motal, in what is now western Belarus, is shrinking; husbands are fleeing the old way of life and running off to Odessa or Kiev or New York. But the novel deals primarily with a more unusual disappearance: that of Fanny Keismann, a young wife and mother.

To the reader, Fanny’s disappearance is no mystery — she has gone to Minsk, aided by the nearly mute Zizek Breshov, to find her sister Mende’s husband (who has been absent for ten months without a word) and compel him to sign a writ of divorce. As the eponymous daughter, Fanny was taught the techniques of kosher slaughter as a girl; since then, she has always kept a small knife strapped to her thigh, ready to brandish it at the first sign of danger. Early in their journey, this results in the deaths of three would-be robbers, and Fanny and Zizek quickly find themselves in the company of two new allies — and on the run from Russian secret policeman Piotr Novak. Novak finds the group almost immediately, which seems to undercut the traditional cat-and-mouse game that the reader may expect. But then he loses them again, suggesting that Fanny may be equally matched with the Russian colonel after all.

The Slaughterman’s Daughter reads something like a folk tale. It’s peppered with Yiddish words and made up of disparate vignettes, perhaps borrowing some of its picaresque style from early novels such as Don Quixote. Iczkovits brings together characters with outsized qualities common to such works — the mute, the villainess, the unrelenting police officer. In a more modern way, though, no character is exactly what they seem. Fanny is described as having a loving marriage and caring deeply for her children, but also shows an affinity for violence, wishing “she could tear down the boundaries of her fate and mutilate the face of anyone who stood in her path to freedom.” Zizek, seen in Motal as a fool, was revered by his former army comrades as “The Father.” Novak has some unquestionably antisemitic attitudes, he also feels “a surge of energy — even happiness” in the company of the Jewish townspeople of Motal; he’s more comfortable there than with his distant wife and sons in St. Petersburg.

The ending of the novel is perhaps too neat, tying up loose ends in the span of only thirty or so pages. But at the same time, the fantastical conclusion is very much of a piece with the rest of the book — highlighting its structure as a folk tale rather than a piece of realism. Unlike, say, Don Quixote, the novel does not seem at all concerned with its protagonists learning “lessons.” Eventually the characters circle back to Motal, bringing the outside world with them, and it seems as if the secluded town could be changed forever. Ultimately, however, there is the more pleasing suggestion that it may simply absorb these dramatic events and go on as it always has.