January 1, 2013

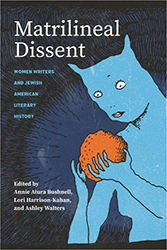

The Superwoman and Other Writings by Miriam Michelson is the first collection of newspaper articles and fiction written by Miriam Michelson (1870 – 1942), best-selling novelist, revolutionary journalist, and early feminist activist. Editor Lori Harrison-Kahan introduces readers to a writer who broke gender barriers in journalism, covering crime and politics for San Francisco’s top dailies throughout the 1890s, an era that consigned most female reporters to writing about fashion and society events. In the book’s foreword, Joan Michelson — Miriam Michelson’s great-great niece, herself a reporter and advocate for women’s equality and advancement — explains that in these trying political times, we need the reminder of how a “girl reporter” leveraged her fame and notoriety to keep the suffrage movement on the front page of the news.

Discussion Questions

Courtesy of Lori Harrison-Kahan and Sophia Pandelidis

- According to Lori Harrison-Kahan’s introduction to The Superwoman and Other Writings, Miriam Michelson’s family was not religious, and Michelson claimed that her Jewish background did not play a significant role in her life (p. 10). Yet, the press identified her as a Jewish writer. For example, The Washington Post called her “a California Jewess who has succeeded with her pen.” After reading Michelson’s work, would you consider her a Jewish American writer? Why or why not? What makes a writer “Jewish”?

- In her foreword, journalist Joan Michelson states that The Superwoman and Other Writings “celebrates women’s accomplishments and documents how far women have come.” At the same time, she writes, the book reminds us of “how much things have not changed for women.” What do you see as the significant changes in the lives of women since Miriam Michelson’s time? What has not changed? What role could journalists and writers play in improving women’s lives and opportunities for gender equality in the future? What lessons can we take away from Miriam Michelson’s work about the way that journalists and writers affect social change?

- In Miriam Michelson’s newspaper articles collected in Part 2, she often uses the first person and becomes a part of the stories she reports. What did you make of this strategy? Does it make her more or less reliable? How does it compare to newspaper reporting you encounter today?

- What surprised you most about reading Miriam Michelson’s reporting from the 1890s and early 1900s? Did you find specific pieces surprising due to their content and/or style? Are there issues that she addresses that remain relevant today?

- Miriam Michelson often drew on her journalistic experiences when she wrote fiction such as the last three stories in the book, which were part of a fictional series in The Saturday Evening Post called “A Yellow Journalist.” How do the style and content of her fiction differ from the style and content of her journalism? Which did you enjoy reading more? What did you notice about the way she transformed her journalism into fiction? Why do you think she transformed the stories in these ways?

- What do you make of the way that Michelson portrays ethnic and racial minorities in her journalism and fiction?

- Miriam Michelson’s novella, The Superwoman, was part of a tradition of feminist fantasy literature that imagined matriarchal societies in which women wielded the power. Since the novella was published in a magazine rather than as a book, there were no reviews of this story and we have little information about how it was received in its time. How do you think readers in her time would react to the story? What makes this story entertaining to read today? How does Michelson use fiction to make a political point? Do you find her strategies effective? Why or why not?

- As a feminist utopian novella, The Superwoman was part of a lively dialogue among female intellectuals about women and power. As Harrison-Kahan points out in the introduction, The Superwoman inverts gender roles, giving women power over men, while Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s novella, Herland, eliminates men to imagine a society consisting solely of women. What do you make of these divergent techniques? How does Michelson’s story compare to more recent examples of feminist science fiction like Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale or Naomi Alderman’s The Power?

- Feminists today are often warned to frame their grievances in a way that avoids alienating critics in order to attract allies. However, many feminists also argue that radical rather than appeasing or accommodationist stances have a greater impact. How radical do you think Michelson’s work was for its time? Do you think readers would be alienated by the feminist content of Michelson’s fiction? Why or why not? Are there ways in which her writing might help gain allies for the feminist cause? Why do you think it gained a popular audience?

- Why do you think Miriam Michelson was forgotten for so long? Why do you think Harrison-Kahan and other scholars are interested in her work now?